| Notes on: Deleuze, G and

Guattari, F. ( 2004) A Thousand

Plateaus.London: Continuum.

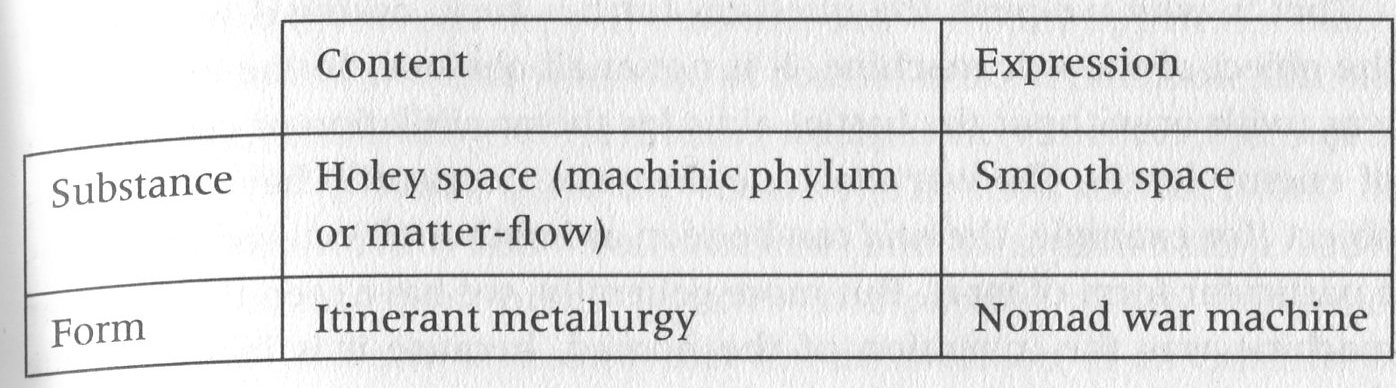

Chapter 12. 1227: Treatise on

Nomadology - the War Machine Dave Harris [Very long. Rather rambling structure, despite its jokey organization into axioms with various propositions. Impossible set of references as usual, at least for someone unfamiliar with French. Wide ranging, but turning on a series of metaphorical oppositions: war machine/state; nomadic/sedentary or nomadic/settled; smooth/striated space; intensive/extensive or metric; singularity/category; nomos/Logos. There is the constant contrast between empirical and the virtual. As we would expect, these distinctions are not very fixed, of course. Again, DeLanda seems indispensable to grasp some of the implications, not least because he has written an excellent book on {literal} war machines. I think 1227 is significant because it was when Genghis Khan died] A French analysis of mythology [by Dumezil, who does rather a lot of work in this] shows that proper systems of domination require both magician-king and jurist-priest [charisma and bureaucracy?]. Here, we see the oppositions obscure/clear, violent/calm, quick/weighty, fearsome/regulated, bond and pact, but they need to operate as a pair, so that developments on one level induce specifications on others. This is 'double articulation', and it turns the state into a stratum. There is no necessary generation of war here - states can prevent military violence by using a police system [or ideology, but we're not allowed to use the term]. If they generate an army, that requires them to integrate a separate military function, a war machine, outside of the state apparatus [outside in ideology anyway]. The war machine offers more flexibility, because it accesses a multiplicity, and this represents potential against the power of the state, 'a machine against the apparatus'[all this is traced to the characteristics of 'Indra the warrior god'(388). Normal bonds are untied, relations of becoming appear instead of binary divisions. We can see this when we look at different sorts of games, comparing chess with Go, for example (389) [apparently, Go is played in a smooth space as opposed to the striated space of chess, drawing on nomos instead of polis [this time] While chess decodes space, Go territorializes and deterritorializes]. Then we move on to Bantu myth about nomadic armies conquering states. This links with all sorts of negative characteristics attributed to warriors, who have no loyalties. European historians have followed this 'negative tradition' (390), and this has produced difficulties in theorizing the war machine. We need to see it as 'the pure form of exteriority', with the state as the classic form of interiority, found even in 'the habit of thinking'. In actual cases, there are mixtures, and the State offers the same forms as the war machine, on the surface at least: hence the success of negative conceptions of the war machine Nevertheless, exterior figures dominate myths and Shakespeare plays [typical of the 'evidence'!] . Actually, the war machine is located between the two branches of the state [military and civil?]. It cannot be reduced to the military apparatus the state uses. The constant suspicion of the military is explained by this connection with something more exterior. As they are not firmly located, men of war seem outmoded or dangerously independent [Greek myth here, 391-2]. Kleist's commentary on Achilles is admired [Penthesilea -- she is even more independent but possibly only because 'love' leads her to abandon everything else] The German war machine that challenged the legions achieved victory, but was still seen as dangerously outside the law. If war machines are not to be incorporated into the state, they seem only to offer suicide and solitariness. Nevertheless, Kleist has identified the key characteristics that link the war machine to modernity - 'secrecy, speed, and affect'(392) [In what follows, speed is to be defined in that strange possibly 17th century way as the ability to make seemingly instant connections across space]. Kleist also notices the radical form of exteriority that liberates feelings from subjects, becoming 'an incredible velocity, a catapulting force… they are no longer feelings but affects' Affects become weapons of war. They appear as various kinds of becoming, including becoming-woman and becoming-animal [dehumanising?]. They are linked together by the war machine. Time itself breaks down into 'an endless succession of catatonic episodes or fainting spells', where affect is too strong, or completely compelling. People are 'desubjectified', and 'no subjective interiority remains' (393). These themes are pursued in modern art as well. This ability to mobilize affects is what challenges the stability of the state, unless it has already been incorporated, say in visions of the state that allegedly transcend the individual [I think, maybe with fascism in mind]. Why do 'primitive, sedimentary societies' not have a state? The usual answer refers to their lack of economic or political development, but Clastres argues that they might actually have been concerned to 'avert that monster' (394). Permanent organs of power are the problem, and non industrial societies had ways to prevent them developing. War itself was an important mechanism, offering a warrior alternative rather than a statesman alternative: war prevents exchange or alliance from turning into props for state power. Such 'mechanisms of inhibition' could operate at the micro level [a French study of street gangs shows a constant system of alliances between groups, preventing leaders from emerging]. High society groups in France operated in the same way, as Proust showed, focusing on prestige rather than power. The pack or band operates as a rhizome and therefore 'are metamorphoses of a war machine'. They tend to operate with a certain indiscipline, a questioning of authority, 'perpetual blackmail by abandonment or betrayal' (395). Clastres is right to say that the state produces a development of productive forces and not the other way around, and it seems to emerge all at once rather than as a result of steady progress. It could certainly never arise from the war machine. The issue Clastres raises is why people came to desire servitude at all [detailed discussion of Clastres 396-7]. Perhaps the state has always existed, always in a relation with the outside as a way of maintaining its sovereignty. Outside factors include 'huge worldwide machines' like religious formations and multinational organizations, but also local mechanisms which assert themselves against the organs of state power, like the new of tribalism of Mcluhan. The outside forces can even combine, as when religious formations develop into bands. Here, their nomos challenges the law, the state form. The war machines do not require some consistent form of sovereignty, but can exist in 'flows and currents' (398), perpetual interactions, and they compete with the state in these fields. [This reminds me of Gellner on the constant tensions between revolutionary and conservative forces in the Soviet union, both equally licensed by Marxism] We find the same divisions in epistemology, with the contrast between royal and minor sciences. Serres has identified the characteristics of minor science: hydraulic rather than a theory of solids, with an emphasis on flux and flow as reality itself; an emphasis on becoming and heterogeneity, with the example of the discovery of the clinamen in Greek thought, 'the original curvature of the movement of the atom' (398), replacing the notion of the straight line with the curve, in anticipation of 'a predifferential calculus' (399). Instead of a geometry of straight line and parallels, we have 'curvilinear declination', a series of spirals and vortices, a space in which 'things-flows' are distributed, smooth spaces rather than 'a striated (metric) one'. The model also focuses on problems not theorems, and considers affects [actually 'affections'] as things that operate on figures, as 'sections, ablations, conjunctions, projections'. Figures themselves are better seen as events rather than something releasing essences, connected to other figures, just as squares exist within quadratures [HP Lovecraft again, as in Difference and Repetition]. In this sense, problems are not obstacles but something that illustrates what surpasses normal structures and shows how to overcome them [maybe], 'in other words, a war machine'... 'the problemata are the war machine itself.' Royal science tries constantly to reduce problems and subordinate them to theorems. [Another feature of this nonempirical world is the 'passage to the limit', which I still do not properly understand - I think it means going beyond empirical limits, or at least making us aware of them and raising new possibilities]. It's possible to extend these insights into thinking of 'an abstract knowledge formally different' from the normal one, and to see a nomad science as developing from its assumptions. There is a constant struggle with state science. State science is happy to appropriate whatever it can from nomad science, but it tries to domesticate it as something that might accompany science, or to ban it. Those practicing nomad science are therefore 'caught between a rock and a hard place' [SIC] (400), trying to avoid both domestication and excessive nomadism. Military engineers show this ambiguity well. For example, there has long been a state-inspired science of military organization, based on 'descriptive and projective geometry', which states attempt to show are simply practical applications of 'analytic, or so-called higher geometry' [DeLanda is essential here]. The same reaction greeted the development of differential calculus, initially seen as only a convenient convention, then as something to be domesticated so that 'all the dynamic, and nomadic notions - such as becoming, heterogeneity, infinitesimal, passage to the limit, continuous variation' could be managed by the imposition of standard rules. Even the hydraulic model was itself subordinated with the development of systems that eliminated turbulence, making the fluid 'depend on the solid' as in the regulation of flow. The real implication was to consider a smooth space and movements that affect all the points of the space, instead of linear projections from one local movement to another. Advocates of the hydraulic model were also capable of seeing social and political implications. Or consider the sea? The notion of a 'fleet in being' shows attempts to recognize the problems of dominating open spaces [possibly, the discussion is drawn from Virilio]. We can also think of work on the rhizome whether it is simply a matter of waves or whether it designates form in general, a particular type of movement. Rhythm can be metricated, but there is 'also a rhythm without measure ... the manner in which a fluid occupies a smooth space' (401). So we see oppositions like this in the development of science at different times [to return to the issue of nomadic vs. royal science]. For example, gothic cathedrals in the 12th century, or bridges in the 18th and 19th centuries illustrate the possibilities. The gothic interest in larger churches is not just quantitative but qualitative, attempting to release a more dynamic relation of form and matter, cutting stones to coordinate forces of thrust. This produces building construction seen as 'the line of continuous variation of the stones' (402) as opposed to the conventional striations, lines and parallels. The task was managed by attempting to affect construction to euclidean geometry, which forms were seen as the best way to organize surface and volumes, but original architects saw all that this would be too difficult, and preferred 'a projective and descriptive geometry' instead. This was echoed by actual advice to stonecutters, or 'an operative logic of movement', generating equations rather than trying to fit formal ones, to do with forces of thrust, 'in a qualitative calculus of the optimum'. In this way classic geometry was brought to its limit, demonstrated in the work of 'the remarkable 17th century mathematician Desargues'. He was eventually banned by royal science, who insisted on using conventional templates to cut stone, even if this domesticated perspective and removed all the 'heuristic and ambulatory capacities'. The journeyman themselves however pursued this more adventurous approach, and they similarly happen to be controlled, for example by regulating their guilds [at first, through the Templars, it is argued]. Initially, modern bridges were subject to 'active, dynamic, and collective experimentation', sometimes even governed [designed?] by general assemblies. One bridge builder saw it as necessary not to choke the river, but to make the bridge vary with the whole (403), but again the state intervened to establish organized schools [including the grandes ecoles]. State organizations can tell us something about collective bodies here. They are differentiated and hierarchical, they relate particularly to families, but there is something that does not neatly fit: they can occasionally constitute themselves as war machines, introducing dynamism and nomadism. We can see this with the development of the lobby, an ambiguous and fluid group. We can argue that the body therefore is not reducible to an organism; for example in the case of the military it has an esprit de corps. This is also an aspect of the nomadic band, which also shows a different relation to families [the family for nomads is 'a band vector'(404), drawing on the ability to maintain solidarity, which might also involve 'genealogical mobility']. This illustrates the potential of social groups like families, which can act as 'vortical' bodies. They are not saying that modern states are the same as Arab tribes, but rather that collective bodies 'always have fringes or minorities that reconstitute equivalents of the war machine', as the examples of architecture above indicate. Sometimes collective bodies can form across the hierarchies. Sometimes, official bodies are forced to open themselves to something that exceeds them, 'the short revolutionary instant, an experimental surge'. The confusion that results brings new thinking about tendencies, poles, and movements. In those moments, the collective body of the state regroups and reorganises, acting like tribal nomads. [back to geometry]. Husserl talked of protogeometry, involving essential shapes or essences, qualities that appear vague, something 'anexact yet rigorous'. We find these problematic figures whenever theorematic ones change. We need to talk about the figures that are '"lens shaped," "umbelliform" or "indented"'(405), for example. If circles are ideal fixed essences, roundness is 'a vague and fluent essence, distinct both from the circle and things that are round'. What these vague essences refer to is something that exceeds thinghood - 'corporeality', perhaps even with an esprit de corps. For Husserl, such possibilities were still seen as supporting normal science and geometry, as limit cases [maybe]. However, we can suggest there are two quite different notions of science which interact 'ontologically' in a single field, with royal science constantly appropriating elements of vague or nomad science, and the latter constantly reinvigorating the former. Huuserl and others wanted to police this relation, as 'the man of the State', to insist the royal science was prime, so that nomad science could only be parascientific. We can now see a war machine as 'necessary to make something round', despite the state's interest in ideal circles. Nomad science is not connected to work in the same way that royal science is. It has a different division of labour. Bodies of nomadic artisans have always caused problems for states who have tried to settle and make them sedentary, either regulating and through corporations, or simply relying on force and power. To go back to gothic architecture, we can see how active these nomadic artisans were, and how the state attempted to regulate them, in ways which included making strong distinctions between intellectual and manual, theoretical and practical labour. In the process, they developed a metric plane, as in official architecture, while nomads developed a different 'ground - level plane'[that is taking into account the characteristics of the ground?]. Metrication and templates also deskilled artisans ['dequalification', 406], and offered a licensed autonomy to the skilled and intellectual. However, there is a constant relation of domination and challenge. In these cases, insisting on precision and metrication is a way of enforcing a particular division of labour, although it would be wrong to see this as just an extrinsic constraint. Instead, these characteristics get imported into royal science, into its '"hylomorphic" model' (407). This involves a split between form and matter, and again the argument is 'that this schema derives less from technology or life than from a society divided into governors and governed'. It also leads to the familiar split between content and expression - matter becomes content, form becomes expression. Nomad science in contrast 'is more immediately in tune with the connection' between them - matter is never prepared and homogenized but is seen as 'essentially laden with singularities' as a form of content, while expression is not just formal but includes various 'pertinent traits'. We see this in nomad art and its connections between 'support and ornament' which does not follow the matter-form schema. Nomad science sees the relation between singularities of matter and traits of expression, 'whether they be natural or forced', and this in turn requires another conception of work and the social field. We can see the two models of science in Plato's terms -Compars and Dispars [pursued 407 - 10]. Compars is the model of royal science based on discovering laws that control constants, where constants are seen as something invariable. Dispars is nomadic science, focusing on 'material - forces rather than matter - form', where variables are put in a state of continuous variation, and equations are more like adequations or differential equations: singularities in matter are sought rather than general forms; individuations are seen as events or haecceities rather than as objects, 'a compound of matter and form' (408). Vague essences are also haecceities. Here, nomos opposes logos, and people could see that the latter had a moral element. For compars, space was homogenous and striated, divided by verticals or parallel layers. It had a tendency to spread to colonise all the other dimensions [and turned into something like Cartesian space, a grid]. Gravity seemed important as a model for universal attraction between bodies: even chemistry was affected, even euclidean geometry implied the force of gravity, as a kind of invariable force. This was the basis for metric or arborescent conceptions of multiplicities, and had a genuine impact on scientific thought [some scientists apparently thought that gravity was literally the universal force], becoming 'the form of interiority of all science'. Dispars did not deny the force of gravity, but insisted on variable effects, something supplementary, something in each scientific field that was not reducible to the basic model, something that insisted on an excess or deviation. Thus chemistry added other forces to those of gravity. Velocity itself blurs the grid conception, with curvilinear motion, with the clinamen as 'the smallest deviation, the minimum excess'. Smooth space displays this best, and therefore has no homogeneity either in terms of the distribution of points or the path between them, focusing instead on local contacts. Here, there is a different notion of multiplicity - 'nonmetric, acentric, rhizomatic' (409) [the example is the system of sounds or colours, which cannot be gridded externally - this was before digitalization, of course]. Oppositions like those between speed and slowness, the quick and weighty refer to qualitative differences in science. Speed, for example its not just an abstract quality of movement, but 'is incarnated in a moving body that deviates, however slightly, from its line of descent or gravity'[no doubt some philosophically significant definition]. Both slow and quick are 'two types of qualified movement', and the qualitative differences remain despite the measurable qualities [the examples that follow involve redefinitions of speed as decreasing slowness, laminar movement as weighty, while rapidity refers to movement that deviates and takes on a vortical form, and this arises from 'a condition that is coextensive to science and that regulates both the separation and the mixing of the two models'- all this is attributed to Serres]. There are two types of science, one which reproduces, the other which follows [through iteration]. Royal science reproduces, induces and deduces, attempting to perceive events externally, and to find laws about them. Nomadic science on the other hand searches for singularities, experiences vortical flows and continuous variation of variables. While the first reterritorializes, the second constantly deterritorializes and extends territory [with a quote from Castenada about how we follow how seeds are dispersed to determine territory, 411]. [Then we get on to metals. Much more is to come] Primitive metallurgy was undertaken by nomadic smiths, despite attempts to see them as following fixed paths on various layers. This is because 'ambulant procedures and processes are necessarily tied to a striated space', which are then formalized as some kind of notion of technology or applied science as an abstraction. This recuperation is chronically likely with nonmetrical multiplicities, in a triumph of the logos. However, there are always sources of resistance in complexity, and the likely return to nomadic procedure, where points becomes singularities again, and smooth space reasserts itself. The state needs both to resist and to integrate such procedures, and often assigns them a minor position. We should not see nomadic sciences as irrational or mystical: they can look like that when they are marginalised; anyway, royal science also has its 'priestliness and magic'(412) [Adorno is very good on that]. It is certainly not the case that ambulant science somehow produces royal science from itself: it continues to depend on following flows in smooth spaces. However, there is a constant attempt to reterritorialize, to produce stable models, sometimes in the name of safety [when building cathedrals][now in the name of technological progress?]. The metric power operated by royal science makes science autonomous [in the sense of depersonalizing it - generally regarded as a good thing]. A cosy division of labour is often the result, where ambulant science identifies problems, and royal science offers scientific solutions, like the relation between intuition and intelligence for Bergson, and making a genuine move away from intuition and the qualities of humanity [again I think they are in favour of this move, although they do not say so explicitly]. The very form of normal thought, not just its content, is conformist, based on a model borrowed from the state apparatus, with ready defined goals and paths. Images of thought like this are are studied by noology. The conventional image operates with a dualism between true thinking from magical capture, and foundationalism, and 'a republic of free spirits...a legislative and juridical organization'(413). The two are interrelated and necessary to one another, but this also allows for something happening between them, something outside the conventional model. We are not operating with metaphors here -the imperium of truth and a republic of spirits are necessary components, and form a kind of interiority as a stratum. This gives thought a gravity, since it appears to explain everything, including the state. The state also benefits from the consensus. Thought like this elevates the state to something universal, rational and right, an ultimate referee. Anything particular appears as an accident, including any imperfections. Before long, any 'realized reason is identified with the de jure State' [classic Marxist critique of Hegel]. These conceptions appear in modern philosophy as well, anything that splits a legislator and a subject in conferring identity. If people obey the legislator, they become masters of themselves, because this is obeying pure reason in the interests of all. Any philosophy 'of ground'[which I am translating as foundationalism] ends by giving the established powers credibility, seeing the organs of state power as akin to subjective faculties, with common sense as a state consensus. The philosopher becomes 'a public professor or state functionary' (415), while the state inspires the reciprocal image of thought. 'In modern states, the sociologist succeeded in replacing the philosopher'[the example is Durkheim of course]. Psychoanalysis also claims to operate with some universal process of thought, which somehow becomes 'the thought of the Law' [the critique of Freud and Oedipus of course]. Noology offers a non ideological way to understand these effects. It would be a mistake, however, to dismiss such thinking - if we avoid serious thoughts, we end up even more doing what the state wants. There are however private thinkers who resist - Kierkegaard, Nietzsche or Shestov [?]. These people live in the desert. They destroy images. [Apparently Nietzsche's Schopenhauer as Educator is the key text for criticizing the conformity of conventional thought]. However, it's not just private thought, but something exterior to thought, something that places thought in a relation with the outside, thought as a war machine. This explains the forms like the aphorism in Nietzsche [which apparently requires meaning to be added from a new external force]. Nor are private thinkers always on their own: instead, they comprise a solitude that is also interwoven with a people to come [or so they would like to think]. This exterior thought maintains its externality and is therefore not just another image of thought, but 'a force that destroys both the image and its copies' (416). Conventional methods operate with striated space and conventional paths, but exterior thought finds itself in a smooth space and there 'is no possible method...only relays, intermezzos, resurgences'. Zen archery offers another example. The war machine is operated by 'an ambulant people of relayers'. That this often leads to failure, only goes to show that nature is not purposive even if it is wise. We can see this in Artaud's letters to Rivière, referring to thought as a matter of central breakdown, vitalised by its inability to take on any form. We can see this also in a text by Kleist, criticizing the notion of the concept as an interior means of control, and stressing instead thought as a proceeding and a process, operating with intensity, not controlling language (417). Such thinking encounters 'an event-thought, a haecceity, instead of a subject-thought, a problem-thought instead of an essence-thought', a thought tackling exterior forces, resisting all attempts to legislate. However, both Kleist and Artaud have become 'monuments, inspiring a model to be copied'[and the same fate awaits D and G]. The classical image of thought claims to be universal, both offering the whole as the final ground of being, and the subject as the principle that personalizes such being. Nomad thought rejects this image, denying a universal thinking subject in favour of a 'singular race'(418), operating without horizons in a smooth space. Apparently, irruptions from Celtic thinking can be detected in English literature. However, there are dangers, of racism or fascism, or the development of a sect, 'microfascisms'. Oriental thinking in particular [specifically in yoga, Zen and karate] can act as a fantasy to reactivate 'all the fascisms in a different way'. The test is to ask whether particular race-tribes are oppressed, inferior, dominated. The point is to construct a smooth space and then to traverse it. We should think of thought as 'a becoming, a double becoming, rather than the attribute of the Subject and the representation of a Whole'(419) Can we discover what is a principle in nomadic life and what is only a consequence? Much will depend on whether conventional paths, through the desert, become important in themselves [for whom?] or act only as a relay, with points to be left behind. The life of the true nomad 'is the intermezzo'. Nomads are not migrants who have a fixed point as a destination, although sometimes the one turns into the other. The nomadic road is not used as a boundary for spaces, but rather 'it distributes people (or animals) in an open space' (420). There is no codified nomos but rather a fuzzy aggregate, again in opposition to the polis. Nomad space is smooth, not organized or subdivided, 'marked only by "traits" that are effaced and displaced with the trajectory'. Nomads occupy space as we know from the famous quote from Toynbee [much repeated elsewhere]: they occupy smooth spaces and do not want to enter striated ones. Nomads offer both immobility and speed, which leads to a necessary distinction between speed and movement - 'movement is extensive; speed is intensive', and while movement describes different states of the body considered as one, speed 'constitutes the absolute character of a body whose irreducible parts of (atoms) occupy or fill a smooth space in the manner of a vortex'. It is like making a spiritual journey without relative movement, operating in intensity but in one place. Speed is therefore an important element of the nomadic war machine. Nomads do not reterritorialize, unlike migrants or sedentary people. Deterritorialization is the proper relation to the earth - ironically, this means that nomads reterritorialize on deterritorialization! (421). The earth also has to offer the possibility of deterritorialization: we think of it as land, but nomads simply as grounds or supports. Possibilities for deterritorialization can appear at local spots affected by climate or changes in vegetation. Once established, nomads 'make the desert no less than they are made by it. They are vectors of deterritorialization'. They proceed in an endlessly flexible manner, 'like rhizomatic vegetation' following local conditions. There is a local topology that relies on haecceities and various relations between the elements. We find a tactile or haptic space, sonorous rather than visual. Striated space by contrast is subdivided and interlinked, crossed by boundaries: it's ubiquity makes it the 'relative global' as opposed to the 'local absolute' of the nomad. In some ways, we can see nomadism in terms of the general characteristics of religion [in the sense of making the absolute appear locally], but religion usually opposes 'the obscure nomos' (422), and attempts to found a centre. In doing this, it converts the absolute and becomes a part of the state apparatus. Nomads couple locality and the absolute differently, through a succession of local operations. In this, they usually stand opposed to conventional religion, with a 'singularly atheistic' sense of the absolute, as a number of religious figures have reported [including early Islam which rapidly replaced the notion of nomadism with the migration, 423]. However, even monotheistic religion encounters fringe areas, largely because it does not simply confine itself to the territory of the state. In this way, even religion can be an element in the war machine, as we know from holy war [I think they have slipped themselves from the war machine to military action here]. The prophet opposes the King. Mohammed did this, and created a particularly powerful esprit de corps. The Christian view of Islam as essentially military forgets or denies military adventures by Christians. Overall, religion as a war machine does tend to produce nomadism, and offers an absolute state which is beyond the conventional [as indeed we know from ISIS]. Even the crusades began with variable directions, as a war machine, and put into process a chain of events sweeping away the old sedentary regimes, even if they ended with new forms of sedentary migrants [massively windy French salon stuff]. Smooth spaces lie between striated ones, between the forest and agriculture. The striated ones limit developments and attempt to overcome the smooth ones. Nomads had to deal with both forest and farmer, and the relative importance of factors associated with both have been discussed by western historians (424). Apparently what the argument shows is that the state form tends to prevail, partly because it is composed of a number of elements, including natural resources: the difference between oriental and western states is that the components were organized in a different way, including some despotic formations. All types faced challenge, from revolt and secession to revolution [with world history interpreted as various relations to dominate smooth spaces, and to confront nomadic war machines directly or indirectly 425]. The state has to striate space, but it also need smooth space 'as a means of communication'. Mostly, it operates to control the exterior by capturing flows of all kinds and turning them into fixed paths. Virilo is right to argue that the main technique involves creating the polis and police. Speed has to be turned into movement, and movement itself endlessly transformed to regulate speed. Whenever there is any form of challenge to the state, when a war machine is been revived, a smooth space appears [as in occupying the street]. States attempt to appropriate war machines, often in the form of blocking absolute movements. Any flows that are not regulated tend to turn into war machines [the example is China in the 14th century withdrawing from regulating maritime flows and rapidly encountering commercially sponsored piracy]. The sea 'is perhaps principal amongst smooth spaces' (427), and there were early attempts to striate it, by deploying suitable technologies. However, one unintended consequence was that relative movements multiplied and intensified [as technologies spread beyond state control?], which produced a smooth space again. We see this with the notion of the 'fleet in being' which holds space from being able to move to and from any point. The air can be dominated in the same way. We see from these examples how the state can occasionally produce absolute movements, reconstituting smooth space. This produces 'a worldwide war machine', exceeding state apparatuses and empowering various military-industrial and other multinationals. This should warn us that smooth space is not always revolutionary and can take on different meanings depending on the interactions that produce them: we also see this in the way that total war and popular war 'borrow one another's methods'. [Now a long and strange piece about nomads and numbers]. Conventional armies deterritorialize soldiers, by organizing them into smaller units [we are really stretching the notion of deterritorialization here]. Numbers are always connected to war machines [as well as armies?], as a matter of 'organization or composition'(428). Nomads thought of numerical organizations first, though [lofty salon stuff about the Hyksos and Moses and the book of numbers]. 'The nomos is fundamentally numerical, arithmetic' [but not geometric]. So we have lineal, territorial and numerical types of human organization. So called primitive societies are lineal, with the clan lineages as segments. There are also tribal segments, however, requiring number again. Number acts as an inscription [nominals?] written on the earth. In state societies, the earth is first of all deterritorialized, becoming an object rather than something active, and property is another example. This requires an 'overcoding', in the form of the territorial organization, where segments are located in a geometrical or astronomical space. In the archaic state, there is 'a spatium with a summit, a differentiated space with depths and levels' (429), whereas the modern state is divided more into a centre dominating a homogeneous space with divisible parts. We find these mixed as well. Both depend on 'metric power', the political use of arithmetic as in imperial bureaucracies operating taxation and election systems, and, later, political economy and the organisation of work. Numbers are used 'to gain mastery over matter, to control its variations and movements'. Number is now neither independent nor autonomous. 'Autonomous arithmetical organization' can be described as 'The Numbering Number', and it relates to conditions of possibility and effectuating the war machine. State armies require the treatment of large quantities, for example, but war machines operate with smaller quantities with autonomous arithmetic, describing the distribution of something in space, rather than dividing space itself. 'The number becomes a subject', it is independent of space: this happens only with smooth space, however. Numbers move through this smooth space. The geometry of smooth space is 'minor, operative' (430), 'a geometry of the trait'[the geometry of the intensive, one of those higher order geometries mentioned by DeLanda]. Numbers are movable. They do not just measure. In nomad culture, the number 'is the ambulant [camp] fire'. Numbers suggest directions [as in the flow between two intensities?]. Numbers are not used to organize armies on the march [rendered by these pompous bastards as 'The numbering number is rhythmic not harmonic']. Sometimes random numbers are important [with a quote from Dune on how to walk without attracting the attention of the Great Worms - hard luck if you have not read it]. Numbers becomes ciphers [that is nominals, with all their other characteristics made irrelevant -the ability to subdivide them, for example]. It becomes an esprit de corps [I belong to the chosen few?] and leads to characteristic strategies such as ambush and diplomacy [I am reminded of the old Maoist maxim about marching divided to fight united]. When it takes the form of a war machine, this numerical organization looks impersonal, but 'it is no crueller than the lineal or state organization' (431). Numbers are used to select from lineages and to direct action against the state apparatus: in this sense, they are themselves a deterritorializing activity which cuts across lineal territory. We always encounter complex and articulated numbers, rather than some large homogenized quantity. Heterogeneity is present, 'fine articulation'. State armies attempt to copy this principle with their own subdivisions, each with a degree of autonomy and mobility. In war machines, numbers are used to join together 'weapons, animals and vehicles' in 'a unit of assemblage'- so one man requires one horse and one bow, for example, or a more complex weapon requires a particular size of crew and animals. The proportion of combatants among other members can be numbered. Logistics can develop ['the art of these external relations'], and is just as important as strategy. Numbering numbers also act in a 'process of arithmetic replication or doubling'(432) [the repetition of the point made above, that lineages are numbered, but also people are selected to make up a special numerical body of fighters]. This is essential, and lends autonomy to the number because a special body corresponding to it is produced. [Lofty stuff about Genghis Khan and Moses ensues]. This doubling process provides the state with its own source of power, independently of the clans and lineages, although there are frequent struggles between the two principles [necessary, our heroes argue, to limit the powers of chiefs]. [And now in fashionable set theory] aggregates or sets are numbered, the union of subsets is performed, one elite subset corresponds to the united set. There are various ways to perform the last operation, and the issue of correspondence also affects state armies. One solution is to draw the elite subset from an already privileged lineage; or to select a representative of each lineage; or to entrust the fighting to a totally different exterior element, like foreigners [and one example is the notion of military slavery with the Mamelukes]. This sort of policy has led to some bad publicity for nomads, as child stealers for example [relating back to an earlier example of Jewish policy of recruiting the first born for military service]. At the same time, the power of outsiders is an important counter to the power of aristocracies or state functionaries, although it can also empower chiefs and their personal whims. For this reason, there is often an emphasis placed on a particular kind of becoming - becoming a loyal citizen, becoming a soldier, while remaining an outsider. Special schools are needed for this, and states have often adapted such schools to provide their own military leaders. 'The nomads have no history; they only have a geography'(434). The triumph of the state has led to a dismissal of nomads as backward, lacking technology, although it is obvious that they had 'strong metallurgical capabilities'[this is going to lead to the extraordinary section on metallurgy], and war machines clearly had some positive aspects. [Winners' history has led to] sedentary categories like feudalism being employed, but what has really happened is that an imperial state has appropriated the war machine, and awarded land to warriors to encourage dependence. Nomad organizations were perfectly capable of distributing land and gathering taxes, by producing a more mobile notion of territoriality and fiscal organization - the numerical principle again. We can still detect a genuine nomadic system in terms of whether land is distributed or occupied. Much of the modern organization of the state can be seen as survivals from nomadic systems. The normal distinction between weapons and tools is on the base of the usage, but this conceals intrinsic convertibility, and the distinction is only recent anyway. In other words 'the same machinic phylum traverses both' (436). There are still differences, however, such as weapons are normally linked with the ability to project or propel something, something ballistic, even for handheld weapons. Tools are designed to domesticate matter and appropriate it, even if it acts at a distance. Tools meet resistance, while weapons have to manage counter attacks, 'the precipitating and inventive factor in the war machine' (436). There is also a difference in terms of the relation to movement and speed. Speed [in this special sense of immediate relations] is connected to projectile weapons. War machines help us realize this vector of speed more generally, as the specific power of destruction or '"dromocracy" (= nomos)'. This helps us distinguish between hunting and war: they are not connected by evolution, since Virilo says enemies are not seen as prey, something that possesses a desirable force to be captured. This is why we find war machines among nomads who raise animals rather than hunt them. Projectile systems are involved in both cases [seeing breeding and training as projection]. War also requires durable and unlimited violence [some analysts, like Elias, say that hunting once did as well]. Breeders want to preserve 'wild animality', and cavalrymen show how to join human with animal movements in a distinctive becoming-animal. This also offered an early release of the speed vector, unconstrained by the pursuit of prey animals. It is the idea of a motor force that has been abstracted. Even the apparent inertia of the war machine at times, its 'immobility and catatonia', which are important in war, can be related to the notion of pure speed. State appropriation of the war machine depends on managing speed by channeling it into a striated space. Speed projected with projectiles depends on immobile soldiers or weapon systems. The counterattack classically involves a change of speed to break equilibrium and recreate smooth space. It could be argued that speed is also a characteristic of tools and is not specific to war machines, and that motors also develop in other areas. But it is a matter of comparing limited to free action, which produces relative and absolute kinds of speed. When we work, we apply a force to a specific body, but in free action we liberate elements of the body and work in 'absolutely a non punctuated space' [all these are 'deductions' from initial definitions, reassertions of the qualities of smooth space]. It is a matter of linear movement compared to vortical: the weapon becomes almost self propelling. The tool presupposes work, but the weapon implies a renewal of the initiating cause. It is clear that the technical element is abstract, undetermined, dependent on a machinic assemblage to provide specific uses and extensions. These assemblages are intermediaries that 'the phylum selects, qualifies and [it] even invents the technical elements' (439). These assemblages define the differences between weapons and tools, or not their intrinsic characteristics. A war machine assemblage liberates free action, not the weapons themselves, and the work machine assemblage does the same for tools. The two assemblages provide the different notions of speed. [In one phrase, 'the "war machine" assemblage [is] formal cause of the weapons']. The war machine adds speed to displacement or free action. 'Weapons and tools are consequences, nothing but consequences' (440). It is clear that specific weapons arise from specific military uses and requirements [the Greek shield from the phalanx, the stirrup producing the cavalry who required a special weapon, a lance]. The same goes for specific tools [deep ploughs if you have a system that produces long open fields]. Assemblages are 'compositions of desire', and desire itself is not natural or spontaneous, but 'assembling, assembled, desire'. Assemblages bring into play passions and desire [the Greek phalanx involves a change from individuality, the dismounted cavalryman forms a new relation with his fellow men. These in turn lead to the development of new kinds of soldiers like citizen soldier, or even 'a group homosexual Eros', 441]. However, the assemblages might produce ['mobilize'] passions of different orders, different effectuations of desire, different conceptions of justice or pity, for example. The 'passional regime' of work is directed at evaluating matter and its resistance, attending to form and force. Passions of the war machine turn on 'affects, which relate only to the moving body in itself', or the counterattack as a discharge of emotion. This is not the same as feelings, which are interior: affects [in war machines only?] 'are projectiles', and are related to weapons, as in the chivalric novel. In war machines, absolute immobility is also a part of the speed vector, producing the specific 'catatonic fits' that precede absolute speed [according to Kleist again -'a becoming-weapon of the technical element' combined with 'a becoming-affect of the passional element']. Martial arts show the same relation between immobility and speed, the suspense of affect before its release [leading to a section on the martial arts as a matter of following the 'paths of the affect', rather than a specific code, 442]. There are relations between tools and signs ['essential' ones]. This arises from work in the modern state, as opposed to the [labour] of primitive societies. Signs move from bodies to objects or matter [signs are not associated with persons any more, but with more abstract objects]. The State must semiotize activity by developing writing, in an 'affinity' between two assemblages, 'signs- tools', and 'writing-organization'[seems you can find assemblages anywhere]. Weapons are more associated with jewelry, as in the decorated weapons of barbarian or nomad art. Such jewelry 'constitute traits of expression of pure speed, carried on objects that are themselves mobile'. They take the relation of 'motif-support'. Despite requiring effort to produce, 'they are of the order of free action', not work [they are not utilitarian?]. They are produced by 'the ambulant smith', who works metal to produce both weapons and jewelry, and they show how gold and silver can become 'traits of expression appropriate to weapons'(443). Metalworking requires a power of abstraction equal to, but not the same as, writing. Nomads borrowed writing from imperial neighbours, but metallurgy, especially gold and silversmithing is the characteristic nomadic art. It did not follow from the creation of a precise code, as in modes of representation, but offered 'more of a linear ornamentation'. Runic writing seems to have been associated with jewelry as an exception, but that was always limited to expressing signatures, or short messages of war or love [obscure references to Danish writing]. Again we see the results of assemblages affecting traits differently. Thus music and drugs are associated with nomadic war machines, but architecture and cooking with the state. What we are pointing to is five differences in the assemblages of nomads and states: directions [outward as projection or inward as introjection]; vector [speed or gravity]; the model [free action or work]; the expression [jewelry or written signs]; the passional or desiring totality [affects or feelings]. Technologies of various kinds are made uniform by the state, but they can still enter into new assemblages and other relations, and help reinvent war machines, as in revolutions and popular wars. There is 'a schizophrenic taste' for converting tools to weapons, and vice versa. 'Everything is ambiguous' (444) [the usual insurance clause at the end of each section]. We might even come to see rebels as 'Transhistorical', drawing on work and war, travelling 'down a shared line of flight'. Certainly, the warrior has long had turned into a military man, and the worker into a functionary, but the old tendencies can still reappear - men of war who know all of its dangers, workers who want to engage in resistance and technological liberation from work. These do not just draw upon past tendencies, but can form 'the new figures of a transhistorical assemblage'(445). They find themselves caricatured in the figure of the military adviser and the technocrats. They must resist the temptation to go back to mythical times. The point is to bring together 'worker and warrior masses of a new type', and to harness the 'virtual changes of knowledge and action' that arise from the world order itself, and use those in new assemblages, borrowing from war machine and work machine [they must have had Italian autonomists in mind, as Lotringer suggests]. The nomads were very innovative when it comes to war, especially in inventing weapons, including combinations of men and animals. Their metallurgy was also particularly innovative, producing breakthroughs such as the bronze axe or the iron sword, particular variations of heavy and light armament, such as sabres to deal with infantry, and heavy iron swords for frontal attacks. We can trace the migration of these weapons to migrations of nomads. The usual view is that these innovations stopped with the advent of firearms, but nomadic inputs were also important: eventually, only the necessary heavy investment that the state could provide limited innovation. This is controversial, and it is not always easy to disentangle the contribution of nomads, however [lots of amazing details about who invented the sabre, 446]. There is often prejudice about nomads too. Much depends on the independent role played by metallurgists, who are not always controlled carefully by the state apparatus, and who communicated innovations among themselves, along 'a technological line or continuum' (447). Metallurgy is one of those activities move that is hard to codify into a science, since there is much variation with raw materials, alloys, and the operations that can be performed - in other words singularities or 'spatiotemporal haecceities', requiring transformation. There are also 'affective qualities or traits of expression' associated with the singularities and operations on them (448) [making a sabre is then described in terms of transforming singularities]. We have discovered 'a machinic phylum', with 'the constellation of singularities, prolongable by certain operations… [which produce]… several assignable traits of expression'.. Where the singularities or operations diverge, there are different phyla, and each phylum has its own singularities, qualities and so on which 'determine the relation of desire to the technical elements'[just a silly way of saying weapons develop according to the purposes to which they are to be put?]. Nevertheless the different phyla can converge, since singularities can be 'prolonged', in a flow of matter and movement between them, producing 'a single machinic phylum'. Flows are both human and natural; they take more concrete forms as assemblage, 'every constellation of singularities and traits deducted from the flow'['deducted' means both deduced and subtracted, as in the definition of the rhizome?]. Assemblages can operate at different scales, with very large constellations appearing as cultures or even 'ages', producing differentiated phyla or flows at different levels, selecting among [disrupting] different possible continuities, and producing differentiated lineages within an over arching machinic phylum. Thus particular singularities, such as 'the chemistry of carbon' (449), will be selected, organized and used in a particular assemblage. This implies a number of very different lines, some phylogenetic[links between blowpipes and cannon] , some ontogenetic, operating within one assemblage, sometimes passing it on to other assemblages [the example is the horseshoe which spread through different assemblages]. Just as assemblages select, so the phylum displays 'evolutionary reaction' as it moves along various threads, develops assemblages, or leaves them - 'vital impulse?'. Some authors have argued for technological vitalism, positing a universal tendency dealing with all sorts of singularities and traits of expression - our heroes prefer a 'machinic phylum in variation'. This flow of matter and energy is 'destratified, deterritorialized'. It can be seen in Husserl's notion of vague essences, which are neither formed things nor formal essences [and have been discussed above], 'fuzzy aggregates' (450), referring to corporeality rather than thinghood. This corporeality lies beneath changes of state of bodies, transformations, and occupies 'a space-time itself anexact', but it also contains expressive and intensive qualities producing variable affects. This is what causes 'ambulant couplings, events - affects'. Husserl tried to use the term to bridge the formally essential and the sensible, but D and G want to see it [roundness is the example] differently - 'as a threshold-affect (neither flat nor pointed) and as a limit-process (becoming rounded)', appearing as sensible things and technical agents like wheels or lathes, but itself autonomous: it produces 'a vague identity' between things and thoughts [could be one of the processes of differenTiation discussed in Difference and Repetition?] This is similar to other criticisms of the 'matter - form model' which assume too much homogeneity, partly because this is necessary if you want to develop laws. This is the hylomorphic model, which ignores activity and affect. However, 'energetic materiality' is implied in the ways in which singularities become forms, and change takes place [including resistance of the material, as when wood fights back]. There are also 'variable intensive affects' affecting our operations on material [the example is the porosity of wood or its elasticity]. Craftsmen know that they should take these into account rather than imposing a form on a matter, treating the wood as 'a materiality possessing a nomos' (451), material traits of expression. We can translate these characteristics into a formal model, but not without distorting them, making variables fixed, imposing equations rather than seeing them as 'immanent to matter - movement (inequations, adequations)'. Such translations are legitimate, but they lose something. We need to think instead of 'perpetually variable continuous modulation' between form and matter, fully recognizing an intermediary dimension 'of energetic, molecular dimension'. We get a fuller picture of materiality by thinking of the machinic phylum, matter in movement, conveying singularities and traits of expression. We can only follow such flows, as artisans have always known. We can define proper artisans as those who have gone off to find the raw materials in the first place, and not have them brought to them, which makes them merely workers. Following the machinic phylum makes proper artisans ambulant, following the flow, 'intuition in action'(452). However, there is also the 'transhumant', on a different sort of journey [the examples given are farmer or animal raiser - their favourite nomads. The term does NOT imply something that exceeds humanity, but a human being who makes transitions, like those who pasture their animals on moorland in the summer and lowland in the winter]. They trace a circuit not a flow, and only follow parts of a flow, becoming 'itinerant only consequentially'. Merchants can be transhumant when they travel only to get things for markets. Nomads are not transhumant, nor migrants, although they can become these afterwards. Sometimes, smooth space itself forces them to be itinerants or transhumants, and mixed forms are common. 'But...we have wandered from the question' (453) [!], And we need to get back to the role played by metals in the machinic phylum. It is this that accounts for the relation between itinerance and metallurgy. Metals and their characteristics help us to see this stuff about corporeality and intermediary dimensions, better than does, say, the relations between other raw materials like wood or clay. Those materials seem to validate the hylomorphic model as a fixed process going through a series of thresholds, but with metal, operations are more fluid, revealing its 'energetic materiality', and providing transformations that exceed fixed forms. [One example is the need to quench metal even after you have formed it to, or to continually decarbonize steel, or to melts down one form to reuse it - the 'ingot-form' was particularly significant, as the basis for money]. Metals seem particularly rigid and fixed, but they turn out to be quite variable, just as does music - 'a widened chromaticism sustains both music and metallurgy'. The characteristics of matter are brought to life, its 'material vitalism' that is not so apparent elsewhere. [Getting into their stride] 'metallurgy is the consciousness or thought of the matter flow' (454). Metals are everywhere, 'the conductor of all matter' [and see DeLanda on the role of metals in developing various kinds of useful syntheses]. The machinic phylum 'has a metallic head as its itinerant probe head or guidance device'. Thought is born from metal, 'metallurgy is minor science in person, "vague" science or the phenomenology of matter'. 'Metal is neither a thing nor an organism, but a body without organs'. It has always been closely connected with alchemy because of its ability to demonstrate the 'immanent power of corporeality' [Let's hear it for artisans], 'the first and primary itinerant'. They follow the matter flow. Their ability to work metal has led them to form collective bodies like secret societies. They relate with farmers and with state functionaries, but they also relate to forest dwellers and nomads, because they have to go where the mines are: 'Every mine is a line of flight, that is in communication with smooth spaces—there are parallels today in the problems with oil'(455). Mines are not important in all empires, so the metal had to be acquired in some other way, through trade, leading to the necessity for politics and commerce. Again the role of nomads and smiths have been underestimated [in the accounts which they happen to be criticizing]. Mines are particularly interesting locations to examine 'flow, mixture, and escape', political struggles including those waged by alliances of miners. It is not enough to operate at the level of feelings, 'the usual platitudes' about ambivalence attached to smiths - the reason for this ambivalence lies in the social relations between smiths, nomads and sedentaries and the 'the type of affects they invent (metallic affect)' (456). Smiths are themselves others and therefore have 'particular affective relations with the sedentaries and the nomads'[affects here meaning something that affects you from the outside]. Smiths are always ambulant. They live in temporary accommodation, 'like metal itself, in the manner of a cave or a hole'[a certain Faure is then used to describe itinerant people in India who tend to create dwellings based on holes and tunnels. In the minds of our delirious heroes, there is a connection with Eisenstein and the film Strike!, which shows 'a holey space where a disturbing group of people are rising', image on page 457]. Itinerants passed through striated and smooth space 'without stopping at either one', and metallurgists are suspected of double betrayal as a result -- neither farmers nor animal raisers. They have the mark of Cain. They feature in various kinds of myth about strange invading peoples. Smiths display 'internal itinerancy', with their vague essence. With their construction of holey spaces, they can communicate with sedentaries and nomads, and others, including transhumants: 'holey space itself communicates with smooth space and striated space' (458). They are doubled, mixed. In Dogon society, they have restricted marriage opportunities. In other empires, they have been both mobile and captured. They are reduced to the status of the worker, but this encounters a problem in that they are also prospectors with links to the outside, to merchants. The ingot form linked them to other metallurgists in 'a line of variation'. They make both tools and weapons. Their activities have diverged, for example in producing different artistic forms. We can explain this in terms of how the machinic phylum 'has two different modes of liaison', 'always connected to nomad space, whereas it conjugates with sedentary space'. When it connects with nomadic assemblages and war machines, it takes the form of a rhizome 'with its gaps, detours, subterranean passages, stems, openings, traits, holes etc.', But when sedentary assemblages capture the phylum and codify its traits of expression, 'a whole regime of arborescent conjunctions' arises. [Last lap. We're going to link together the war machine as a kind of expression, with metallurgy as its corresponding content. The thrilling diagram below is found on 459, just to give us practice with Hjelmslev].  How do actual battles relate to war machines, and how does the war machine relate to the state apparatus? In the first case, battles themselves can be both sought and avoided - with guerrilla warfare as an example of the latter [especially in the case of DH Lawrence, whom they admire]. War also escalates beyond battles into total war. However, guerrilla war and 'proper' war borrow from each other. We certainly cannot argue that war is the same as the battle. Similarly, war machines need not necessarily have the war as their object - they can organize a raid, for example. The war machine was originally a nomadic invention to occupy smooth space as its 'sole and veritable positive object (nomos)' (460). We only get military action when war machines collide with states or cities. In this sense, war itself supplements or necessarily accompanies the war machine, but war machines can develop without having war in mind at first—the example is Moses only gradually coming to realize that he will have to fight. States were not originally formed to make war either, and were able to dominate people using other agencies like the police. However, they soon learned from nomad war machines and their success. The problem then became to appropriate the war machine, and this changes the original functions of the nomadic war machine: only then does the state war machine focus on war itself as its object. There is a great deal of historical variation in terms of how this happened. The nomad war machine did not aim centrally at war, and so it was vulnerable to being appropriated - 'the hesitation of the nomad is legendary' (461), quite rightly because the options are to return to the desert or be incorporated into an empire [Genghis Khan managed a compromise, they argue]. At the same time, the state takes a risk when it appropriates the war machine since it can require an enormous system to subdue it. There are other differences in the concrete forms that state appropriated war machines can take - whether to have a professional or conscripted army, for example, or whether to fully integrate the military or simply admit a particular caste of warriors. We find mixtures and transitions. The means of appropriation also varies, for example between using 'territoriality, work or public works, taxation' (462). Each has its disadvantages. Clausewitz famously argued that '"War is the continuation of politics by other means"' (463), but this is so only in a particular context or aggregate, assuming a particular kind of war aimed at bringing down enemies; wars submitted to state aims and effectively pursued by states; the management of the swing between limited and total war. If we look at real wars not idealized ones, we run into the problem that war machines do not necessarily have war as their object [I think the point here is to suggest other possibilities which lead to a criticism of Clausewitz]. The nomad war machine was 'the content adequate to the Idea'[the inspiration for the concept?]. [In their perverse way, they argue that this pure war machine was only realized by nomads, who therefore remain as an abstraction, because they are not a pure category. They want to preserve this notion of the ideal war machine, which is not the same as the military or the state version, and only actually turns to war once it has been allied to the state - maybe, 464]. It is state appropriation of the war machine that requires investigation, how it evolves into total war [see DeLanda]. Capitalism is clearly a factor here, with its development of constant and variable capital, so that whole peoples get involved, turning eventually into total war. There is a tendency for war to exceed political limits and to pursue unlimited objects: states unleash a war machine which becomes greater than them. A crucial figure here is fascism embracing war 'with no other aim than itself', or but there is also a postfascist figure focused on peace and the need to dominate the whole earth to secure it, 'a form of peace more terrifying still', a state formed smooth space. The war machine dominates in the name of order, moving beyond state control. Thus the war machine has become stronger and stronger 'as in a science fiction story' (465). The enemies are no longer clearly specified. A mixture of local wars and anti guerrilla wars have ensued. However [and there always is a however], advanced capitalism also can 'continually recreate unexpected possibilities for counterattack, or unforeseen initiatives determining revolutionary, popular, minority, mutant machines'. Anxiety about unspecified enemies shows this. War machines always have had a variable relation to actual war. They have two poles: destruction and war become objects without limits as we have just seen; the other pole, which 'seemed to be the essence' (466) takes as its object 'not war but the drawing of a creative line of flight , the composition of a smooth space and of the movement of people in that space', with actual war as only a supplementary, which can even be directed against the state. The assignation of the war machine to nomads was 'done only in the historical interest' of showing the ambiguity and shifts between these two poles. Nomads themselves are not essential: they 'do not hold the secret'. Artists or other ideological movements can turn into a war machine if they construct a plane of consistency, act 'in relation to a phylum', a line of flight, a smooth space. This constellation defines the nomad and not the other way about. Modern forms of people's war do conform to the essence of a war machine if they 'simultaneously create something else'. There are always dangers, in that lines of flight can become lines of destruction, and planes of consistency can become 'planes of organization and domination', and the two poles interrelate and can borrow from each other, as in the construction of a smooth space by capitalist war machines. Luckily, 'the earth assert its own powers of deterritorialization, it's lines of flight, its smooth spaces that live and blaze their way for a new earth' (467). The trick will be to manage the incommensurable quantities in the war machine, steering it towards the right pole. If we manage this trick, we can use the war machine against the apparatuses that appropriate it [leading to ch.13]. back to menu page |