|

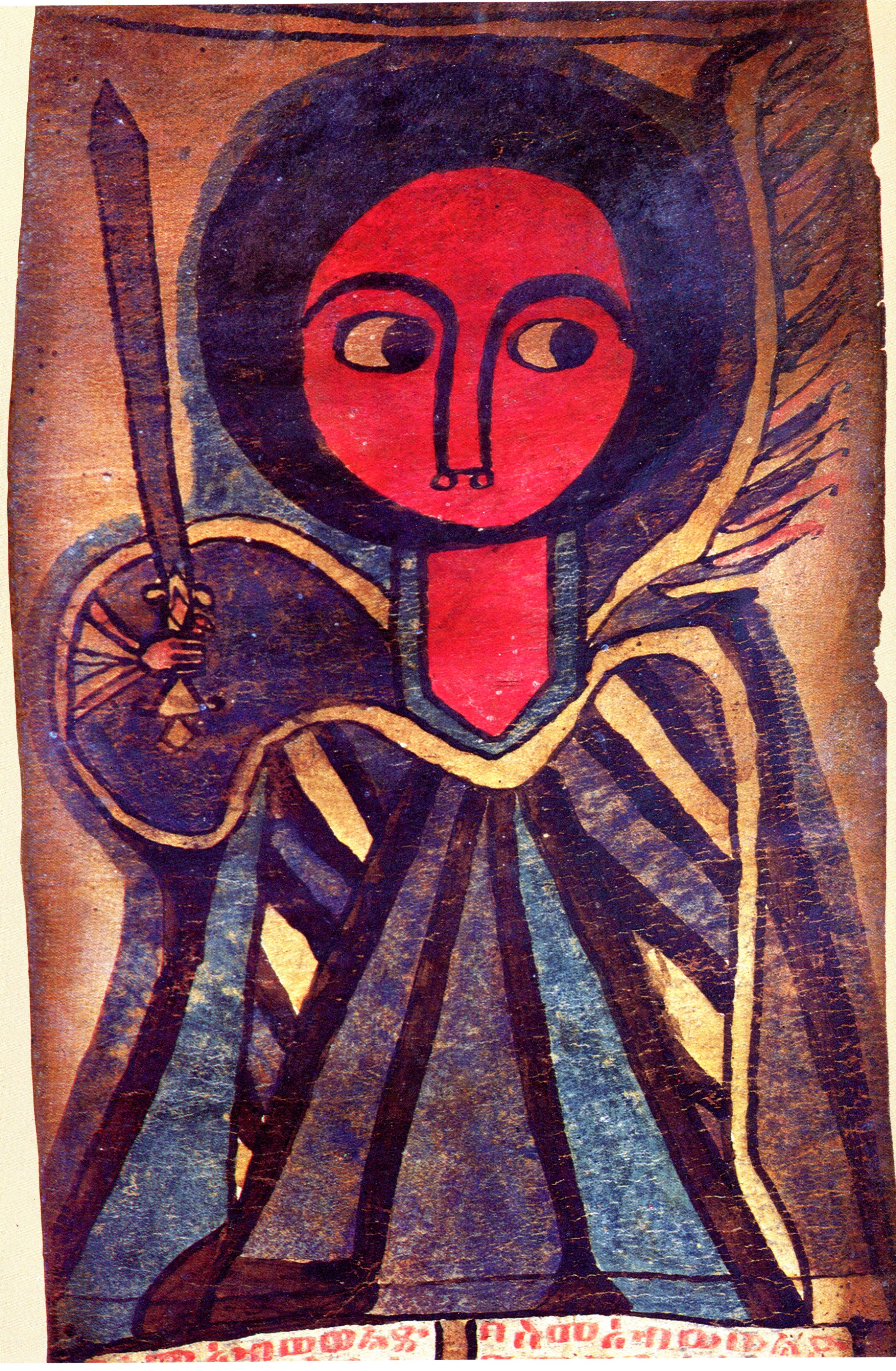

Notes on: Mercier, J (1979) Ethiopian Magic Scrolls. (Trans R Pevear). George Braziller Inc: New York Dave Harris [NB This book is cited as a major source for Plateau 7 on faciality, for Deleuze's and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus. They say: 'Mercier's analyses in their entirety constitute an essential contribution to the analysis of facial functions' (note 14, p.589.). But I'm buggered if I can see how it contributes to their very weird Plateau] Ethiopian civilization began in 500 BC, Christianity arrived in the fourth century A.D. there was a split from the other churches. A religious and literary revival began after the 13th century. The Christian population undertook many conversions of Jewish and pagan believers through stories of the saints' lives. Muslim dominance began the 16th century borne by Omoro minorities. In the 19th century, there was a christian consolidation launched by the ruling class and featuring summary conquests of earlier land. Most of these scrolls date from the 19th century. They are found written in various languages, there were mostly read by Christian and Jewish populations, but some Muslims too. As talismans, the scrolls were part of a deeper mystery. There seem to be two accounts of how they arose: (a) they date from before the Flood and are revelations by the Devil; (B) God revealed them to various old Testament figures especially Abraham and Solomon. (A) in a gloss on the Book of Enoch, the sons of Adam took different routes. Seth and his descendants retired to the mountains where they lead virtuous lives, but Cain and his descendants lived in lust and pleasure on the plains below. The devil (Azaziel) attempted some of Seth's descendants to come down intermingle with those of Cain. They brought with them various Divine secrets including the use of red and black ink, the names of God, and the construction of talismans. (B) the wisdom of Solomon is of divine origin and he was able to call up devils and get them to help him build the Temple. He also had a ring containing the secret name of God. Both of these accounts bear a Judaic gloss and subsequent Christian elaboration. What is unknown is exactly what role was played by each of the religions and what medicine and painting were like before they were introduced. It is likely that Ethiopian was a region of transmission, mixing various influences. Christianity attempted to oppose earlier influences but ended by absorbing them. One earlier belief turned on the signs of the zodiac and their influence, direct or through spirits, on parts of the body. Curing illness involved increasing or weakening the power of corresponding stars. This was done by wearing an amulet containing various substances that strengthened or opposed these influences from plants, animals, or stones. The latter were sometimes engraved with the image and sign of the decan (sections of the heaven reflecting the signs of the zodiac). Early Christians including Paul did not deny this zodiac influence but maintained that Christ could deliver people from bondage by ignoring planets and wondering devils. Popularly though, words and signs were still awarded transcendent power. Christian phylacteries were designed following Old Testament practices, and Christian themes gradually came to supplant pagan motives. Phylacteries of precious metals or lead, various papyri and parchments were inscribed with prayers, powerful names, crude sketches of figures or radiant faces. Little is known about Jewish influence earlier, although books of the Old Testament had some importance. There has clearly been a Muslim influence affecting traditional medicine magic and talismans. For example 10th century Muslims used protective scrolls in Egypt, with similar layout of text and images and even similar motifs, 'winged figures, interlacing squares, seals'. A particular person, Al Buni, had influence. Some Ethiopian talismans are almost certainly, although they have also been elaborated — extra names of angels and God, and a 'knotwork of lines and letters in which eyes and faces appear' (10). Various historical figures apparently compiled anthologies. There are mentions of the use of amulets and talismans in various early texts, although we don't know the details. Instead, European collections offer the best access to early pieces, and they were not much offered to the public because the style of the painting was seen as shocking. Ethiopian concepts are not simply those found in Western ideas of magic. It is better to think of exorcism at first. Strictly, only the Gospels and the Psalms of David are allowed in orthodox christian exorcism, although the lives of saints may also be read, and the 'Homelies of Michael' (12). The names of God are not supposed to be included, although this is not actually forbidden. In one example, three priests read from a collection of protective prayers, including Christian ones, a jug of water in which plants with relevant properties are steeped is placed on three stones; the ritual goes on for a week with the reading of seven sections each day, then there is a blessing involving pouring the water over the victim. Talismans are included, including an image of the devil bound by the cross. These elements seem to permit toleration by Christian dogma. The reciting of the names of God is tolerated as a religious exercise. The really forbidden element is to choose a text that matches astrological signs: then we are into divination and idolatry. Writing a particular prayer on the scrolls avoids these accusations, even though it contains the names of God. When there is a reference to astrology, the process is based on ancient texts including those in Greek. Each letter of the victim's name and of his mother's name is given a number. These are added up on a scale based on the number 12, and the number of the zodiacal sign that corresponds is added. Each sign corresponds to various elements like 'aggressive spirits, protective angels, prayers, rites to be carried out, animals to be sacrificed, colours, sometimes images close '(13). Modern examples have depleted astrological content Why do talismans persist? They seem to have retained their links to folk medicine based on plants and animals — they deal with the spiritual side of the disease, which is not immediately apparent from the symptoms. Sometimes a past life will be scrutinized for causes [often very specific ones like whether you cut wood that day]. Various healers ['dabtaras'] will offer different sorts of advice, and it is popular to visit various healers, especially among young women — herbalists, priests, scribes, teachers and even those priests in charge of cults 'analogous to Haitian voodoo '(15). Each healer can order a scroll to be made, and there is some variation. For example, after a religious exorcism, the priest might copy onto a scroll the best passages from particular books which have been used; the cult priest can go into a trance and his avatar can identify the spirit responsible and the remedy, which can then be written on a scroll; the sick person themselves may contact the avatar and prescribe various practices like animal sacrifice, and again the priest will produce a scroll; the cult priest prescribes a cure using his own resources, and possibly including various rituals to drive out impure spirits and then pray to the avatars, again with the final preparation or copying of a scroll. Scrolls are produced from rituals, which may include self purification, animal sacrifice, subsequent rituals involving the animal sacrifice, including collecting the blood, more ritual washing, and finally a ritual feast with relatives. The skin of sacrificed animals would be dried and processed into parchment. Strips are cut to equal the height of the person which therefore protects the client from head to foot. Then prayers and talismans are written on the parchment using a pen made from a reed or from asparagus. The prayers are copied in black ink. Red ink provides the introductory formulae ('"In the name of the Father, the son..."') or emphasis for particular names (16). Sap from ritual plants might be included. Colours are made in a special way. Black ink is made from soot scraped from the bottom of the cooking pot, mixed with particular leaves including those of the olive and resin from the acacia, and cooked with special butter. The mixture is left to dry and then re-dissolved in a solution 'made from roasted and powdered wheat' (17). Red ink is made from sunflower petals and red aloe and mixed with resin as before. Yellow ink comes from the petals of yellow aloe, sunflower and egg yolk, green ink from certain leaves [including datura, I notice]. Many prayers protect against the evil eye, the eye of the witch, devil or '"the eye of shadow"' (19). One classic source is the story of Christ's vision of the old bewitched woman misbehaving at the Sea of Galilee: Jesus spoke the names of God which reduced her to ashes. There is a Muslim equivalent. The prayer called 'the Net of Solomon' is particularly important. Demon blacksmiths appeared to Solomon in a dream and brought him to their Demon King. Solomon was protected by the grace of God and spoke some words of power, including '"Lofham, lofham..."', which reduced the followers to ashes or drowned them. Solomon then struck the King and commanded him to give up secrets like the evil spells behind miscarriage, sin, shape shifting and so on. There are many other texts including passages from the Gospels, or various names of God revealed to Moses or others. Knowing the names of God is particularly powerful and enables mastery of the spirits. However, most of the talismans are made up on the spot or are derived from others which have to be copied. Sometimes Celt priests specialise in either making talismans or writing. Some seem quite identifiable as the work of individuals. The last stage is to insert into the prayers the baptismal name of the client, which is sometimes kept secret otherwise, and then to make a case from pieces of red leather. Scrolls are often carried with people hung by strings. Women must not wear them during menstruation or after sex. Scrolls under the pillow can stave off nightmares. They assist deep breathing and prayer. They seem to be refreshed by having the priest read the scroll on a visit. Sometimes scrolls are put on the central post of a house facing the door. If a person feels ill, a scroll is immediately brought and unrolled. This can produce a violent fit as the devil resists. Then the devil often tells his story and can promise to leave and not come back. There are regional differences in design and use. Some people use scrolls and simple substitutes from religious books, whereas others never separate from their scrolls. The more relaxed ones, from the Tigray region, often lend scrolls, and for this reason, they have been easier to collect. Cult priests often travel widely, however and practice their arts as a form of earnings. However, the priests themselves organize scrolls into two groups, figurative paintings and talismans. The church is less happy to accept the latter, often because they offer analogues of the names of God or imply demonic revelation. There is a popular division as well, with figurative painting telling the story of a person, whereas talismans are revealed by invisible Demons. Figurative painting began with very early Christianity, and images often depict Mary holding the infant, the crucifixion, portraits of Mary and so on. The paintings keep alive the memories of the events and people. Religious painters must study religious history and often follows set piece exercises in drawing, referring to the image of St Michael or whatever. Particular conventions emerge during this training — that the rainbow has four colours, that the coat of St George's horse is white and so on. Whole canons emerge to govern forms and colours. Colleagues will sometimes share their expertise about the use of talismans, and this can include advice about design. Figurative painting is like photography, aiming to represent the entire figure, and 'the exact appearance of things' (24). Talismans reveal what is hidden, however a spirit might be hidden on the person or it might appear in different guises.The talisman, together with the names of God, opposes, interdicts, protects and cures. They are not considered as abstract but as 'intimately connected with the sick person's life, the places he frequents, his moments of hallucination, the spirits that attack him' (26). The style can be compared to those other works of religious and decorative art, some of which feature the same themes '(angels, crosses, knotwork)'. So some of the figurative drawings on the scrolls are 'graffiti', found on all sorts of religious texts including Greco-Egyptian ones. However, the deliberate construction of figurative images reveal the importance of a particular religious style, associated with academic schools such as the 'school of Gondar' which emerged in the 18th century in Ethiopia. It features realism and impressions of richness and opulence. Images like this are supposed to remind Demons that Saint Michael overcame Satan, to stand for the divine beauty and power. [There is also reference to Susenyos overcoming Werzelya — Ethiopian equivalents?]. There is also a geometric style, frequently appearing, enough to be called traditional. There are sociopolitical dimensions too. Figurative art is connected to the centralization of authority, political and religious, for example in the person of a particular emperor in the 15th century [Gondar is another one in the 18th century]. Geometric art is connected with the local authority of the monasteries and the local healers. What has emerged has been a split between public and official religious art and talismanic art. Official art perpetuates realism and pomp, geometric art is personal and secret and based on the constant renewal of traditional geometric style, including knot motifs. There are also links apparent synchronically, common motifs, developed and modified according to particular demands. For example there is a 'simple and frequent shift' in the use of a four petalled rosette. Diagonals can be emphasized to bring out the shape of the cross, whereas diagonal ovals can be treated as eyes, in which case it becomes a talisman — examples as in the diagram below. There are more complex transformations as well, including cases where rosettes or shapes produced by crosses become eyes, and crossbars can become a face.  [This must have been what excited Deleuze and Guattari]. Traditional geometry is sometimes centred around eyes. We only have present-day accounts, but one of them is that the talismanic reproduces the vision of the Demon, but in a liberating way. 'The whole design goes to reinforce the power of the eyes' (30), and these are supposed to act here and now to protect or deliver sick people from spells and possession. Although design is based on eyes are typical, there are other designs to, sometimes referring to explicit symbolism, or diagrams copied from particular books of protection. One example has a diagram where rosettes and eyes are surrounded by a wall, and discs represent the scapular robes of protective angels. We see here 'a play of metaphors and metonymies'. [An example of a metonym is provided by the fringe of a robe or the crown of the headpiece]. These interpretations are not written down. The most archaic talismans date from the 17th century, and are scrupulously copied today. Explanations turn on their use and the prayers connected with them, although sometimes the symbolism can still be interpreted immediately. For example ringed signs stand for chains binding Demons. Sometimes knotwork is composed of letters, reproducing 'effective speech'. Overall, there is a good deal of signification, although it might be going too far to consider the talisman as an image of a magic invitation. There is still room for interpretations rather than one truth, 'the multiplicity of possible invocations which can magnify its effect' (31). It is clear that we have different types of talisman. There is often little writing, and only 'specular' images. Knotwork can turn into a silhouette of a person, and 'the visual effect of entrapment is accentuated by the centring of the design upon the eyes'. The cultural context is important, so that books of protection assume literacy, and so can act as reminders or copies of ancient models. For the illiterate, there are scrolls, adapted to the sensibilities of 'illiterate peasants'. Priests also alter their work according to their knowledge of the sick person's actual life, although they draw upon understandings of affliction and the way to guard against it by expulsion or protection. We often find a 'surprising mixture of spontaneity and learning, terror and reassurance' (33). The pieces should not be seen as art but as medicine. [Considerable commentary then ensues on individual examples, which is obviously hard to summarize. Note that some of the images have been stored online. I offer a sample here:] Plate 4 Guardian Angel [apparently Fanuel]  The double line enclosing the curve is often used. It is not designed to isolate figures from [detailed] backgrounds: backgrounds in this case contain the same colours. As the forearm and the oversized head shows there is no intention to reproduce perspective. What we see is 'the closeness of and spiritually, the importance of the face and eyes — the only significant parts of the body [depicted]. Plate 9 Eight – Pointed Star  The face within an eight pointed star is common and characteristic, and also open to many interpretations. The eight pointed star seem to be a 'universal motif' (56), and is particularly found in Islamic culture as a talisman. Perhaps it is based on the design on Solomon's Ring. The name of the clients or of the angel is usually written in the central space, but, particularly in Ethiopian works [so these can hardly be typical] there is a face. The faces connected with a prayer and so it has to be included. This gives it a local identity but also generic meaning — 'the face of God, an Angel, Demon, a man, and so on). The points indicate the directions of the talismans power, against evil from the East and so on. They also appear as radiance or wings that enable the face to move. Each of the wings might have its own angel, as in one of the apocryphal holy texts: 'eyes, face, and wings can all be angels'. There is compatibility with Christianity since we can also detect the cross of Christ with the saviour's face in the centre. Plate 13 Protecting Figure  The enormous eyes and head, the rings round the eyes, and the same colour used for body and background are all typical of the aesthetics of the scrolls. Again an eye stands for the whole figure, and the eyes on the shield show a protective potential. When eyes are drawn on objects, the point is to give the object of protective function. This is the distinctive function of the eye in talismans: 'The eye is less a conventional theme than a mode of portrayal characteristic of the relation existing between the talisman and the possessed person looking at it' (64).

|