|

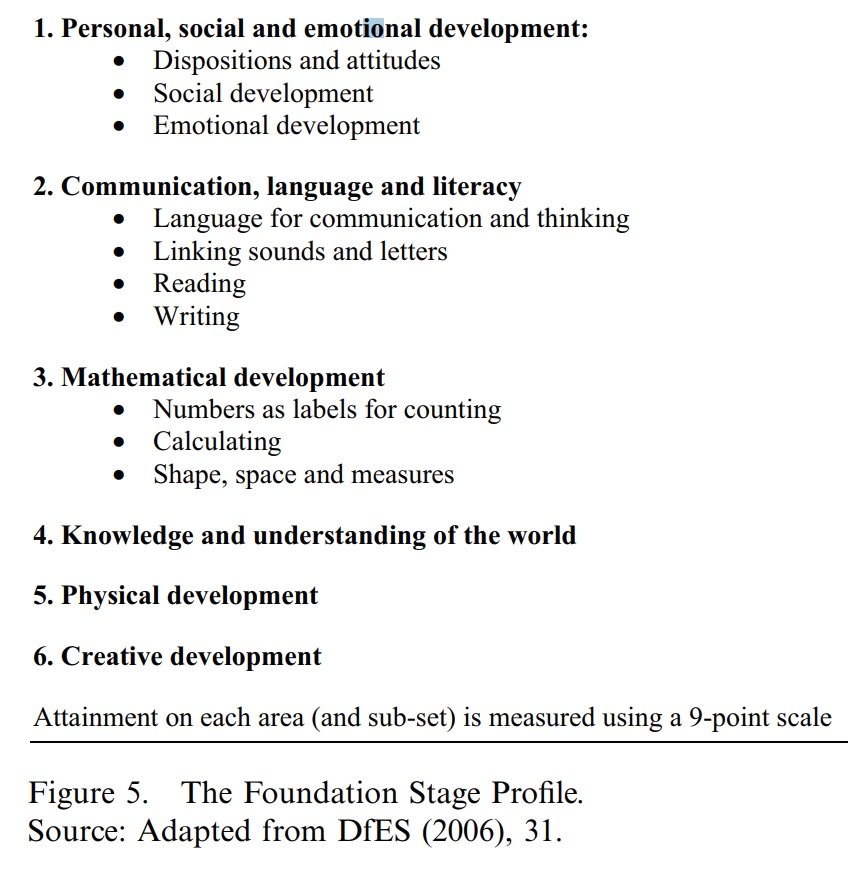

Dave Harris This paper considers the effects of fracking, setting and tiering in secondary schools which amounts to 'a new eugenics whereby Black students are systematically disadvantaged, blamed for their own failure by assessments that lend racist stereotypes a spurious area of scientific respectability' (231). The Thatcher government began this reform as part of their neoliberal educational policies. There was increased state direction of the curriculum, more high-stakes testing, the publication of performance data and other attempts to introduce market principles. These have continued into the present day. Sorting, selection and separation is particularly prominent and has spread globally. It is based on 'core neoliberal assumptions' that there are natural differences in '"intelligence, motivation, moral character, et cetera"… "The cream will always rise to the top… The best way to make sure this happens is through individual competition based on equal access to the markets"… "Those who prove to be unfit… Should receive a minimum level of support"' (quoting Lauder et al. 2006)' (232). Race is not addressed specifically but outcomes will find themselves in racist oppression. Research focuses on Black students which is 'especially significant'. They are the only minoritised groups where reliable national data dates all the way back to the reforms of the 1980s. They are also the 'most prominent in terms of political mobilisation around the issues' so a great deal of qualitative research exists exploring the complexities. This group also 'experience the worst of the changes… The most frequently excluded from school and among the lowest achieving. The research also focuses on the 'Foundation Stage Profile' (FSP) which had a particular effect on Black achievement. Overall, this is a colourblind façade of standard reform, but this conceals a racist reality, a '"new eugenics"' enacted via beliefs in immutable individual differences can be measured and are fixed. Performance in assessment leads to systematic differences in treatment and therefore inevitable unequal outcomes. Practices include: Tracking. In the US there are different tracks steering students towards academic classes or general and vocational tracks. Minoritised students tend to be overrepresented in the lowest tracks, the restricted curriculum, 'less stimulating teaching' and and lower status teachers. Setting in the UK claims to be based on ability and is common. Hierarchical teaching groups are separated for one or more subjects. Individuals may be in different places for different subjects, but 'in practice… Students tend to be placed in similar sets across the curriculum' (233) [referencing among others Gillborn and Youdell 2000]. Both political parties support this approach and see it as raising standards, although the international research evidence casts doubts. Recent Tory governments have committed to even more '"aggressive setting by ability – in effect a grammar stream in every subject, in every school"' (Cameron). It is likely that we will find the same kind of racist processes and outcomes as with American tracking. Research has consistently found that when teachers are asked to judge the '"potential", "attitude" and/or "motivation" of their students they tend to place disproportionate numbers of Black students in low ranked groups' [lots of references p 233, including some based on data from Aiming High, showing ethnic differences [and gender] in membership of the top set in mathematics among participating schools. Those that do well in GCSE exams later are also 'generally more likely to feature in the top maths sets earlier in their school careers' (234), so there is an 'association between set placement and final achievement'. This would also be the case if there were some constant differences in ability, but 'a more critical perspective' suggests that groups do well 'because they are placed in higher sets' [original emphasis]. Teachers decide allocation to sets on different criteria, not just test scores, not just prior attainment, but also 'disciplinary concerns and perceptions of "attitude"' [more references]. Even people with matched attainment at age 14 get different results at 16, 'depending on which set they had been placed in ': those in top sets '"averaged nearly half a GCSE grade higher than those in the middle sets, who in turn averaged 1/3 of the grade than those in lower sets"' [citing William and Bartholomew 2004]. Setting also 'largely determines' the tier of GCSE examination. Tiering was largely adopted in 1988. There are two tiers in most subjects, three in maths until 2006. Students can only enter one tier and there is a limit on the grades available, both higher and lower: those in the foundation tier can never score better than a grade C which can mean that 'study at advanced level may be out of the question'. In the third tier in maths, even a grade C could be denied. Youdell and Gillborn (2000) found that 'two thirds of Black students in London secondary schools were entered for maths in the lowest tier' (235), and subsequent research confirmed these findings, such as the Aiming High research (which found the same with English — the references is to the Tikly et al. study). The 2007 Strand LYSP found that 'several minority groups are underrepresented in the higher maths tier', and inequality remained among Black Caribbeans even after controlling all the other variables 'including social class, prior attainment, parental education, self-concept and aspirations'. It seems like setting and tiering operate 'in a cumulative fashion' to compound inequity until 'success can become literally impossible'. There may be no 'deliberate attempt to discriminate against Black students, but the combination of systematically lower teacher expectations plus institutional separation… Led to outcomes that are racist [original emphasis] in their impact if not intent' Gillborn and Mirza (2000) looked at race, class and gender in a national report to review the evidence provided by OFSTED, referring to 118 local authorities. Data on ethnicity was provided from the age of 11 onwards, but six authorities also monitored achievements from the age of five. These data show Black attainment fell relative to the local average 'as the children moved through the school': in one case Black children were the highest achieving all groups in the baseline assessments. There is a graph comparing the local average with the proportion of Black kids attaining the required level in national assessments at ages five, 11 and 16. At age 5, Black children were 'significantly more likely to reach the required levels, and were even '20 percentage points above the local average', but at age 11 they were 'performing below the local average' in the same local authority, and by 16, Black children were actually the 'lowest performing of all the principal ethnic groups: 21 percentage points below the average' (236). Other research they had undertaken showed a similar pattern between the ages of 11 and 16, using data on 10 local authorities in and around London — again Black students dropped more than 20 percentage points. Having data at age 5 particularly challenges the view that Black children are poorly prepared for school, and this even got into the press! However, the system of assessment on admission to school changed, and so did patterns of attainment: 'Black children are no longer the highest achieving group, in fact, they are now among the lowest performers'. The foundation stage used to mean the period between the third birthday and the end of the second primary school. The foundation stage profile (FSP) replaced the old baseline assessment and now, every child was 'subject to a national system of assessment at the ages of five, seven, 11, 14 and 16'. The results are recorded by the local authority and monitored by the Education Department. Assessment is 'entirely based on teacher's judgements' (238), on '"accumulating observations and knowledge of the whole child"'. It is a complex assessment with six '"areas of learning" subdivided into 13 different "scales" which are assessed individually in relation to specific "Early Learning Goals"'. The whole system was 'introduced hurriedly and with some certainty, and even the Education Department warned that the results should be treated with caution at first because teachers had received inadequate training, and they refer to the first results as experimental.  The data on ethnic breakdown was published in 2005 referring to 1 of the 13 scales. White students were the highest performers, even though 'Indian students perform much better than Whites at age 16 in the same year' (239). There were possible contradictions between the new findings and previous results on the old baseline scales. However it was claimed that the pattern from one scale was common across all of the 13 scales: that Pakistani and Bangladeshi children perform less well, followed by Black African and Black Caribbean, with '"all [ethnic groups] scoring less well than the average on all 13 of the scales"'. This was contrary to the older belief that Black children performed quite well on entry, although this was widely shared — the Education Department made no comment. The received wisdom was 'turned on its head', and suddenly 'Black children moved from being overachievers to underachievers'. The assessment scheme had produced these outcomes even though it was acknowledged to be '"patchy"' — yet the results stood and the questions for schools were erased. Perhaps the situation would improve as teacher judgements improved, but this has not been the case. Data for 2004 and five saw that 'numerous minoritised groups still achieving below the national average… In all 13 scales and for both years… [Including] Black Caribbean, Black African, Black other, Pakistani and Bangladeshi students' and the size of inequalities grew. The assessment was changed in 2006 and no ethnic breakdown was published. A single benchmark was produced, but even so 'the new results were plainly marked by both gender and raced inequalities' (240). In particular 'for both sexes White British students were among the highest ranked children… The lowest achieving groups were the same for each gender: Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Black African and Black Caribbean'. When combined, race and gender is particularly important for the lowest ranked groups — so that two thirds of boys are judged as not having a good level of development in 'Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Black African and Black Caribbean groups' (241), and these scores are used to judge progress in later assessments. As a result, Black children are now among the lowest rated groups and lower attainments are no longer seen as a relative drop in performance but something predictable and in line with their starting points. There have been rapid adaptations to this new story, including government statements about race equality: in 2006 the government decided that local authorities should identify the factors among ethnic groups that hindered their development, the explanations for Black failure as 'an unfortunate fact'. There used to be a debate in America claiming that African-Americans and underclass Whites were 'genetically predisposed to lower intelligence and higher criminality' as in the authors of The Bell Curve, who included Jensen and Eysenck. Posing as experts in intelligence, they argue that genetics played a bigger role than environment in creating IQ differences, according to various scientific studies, so that 'the average White is more intelligent than 8/10 African Americans'. These views have been 'demolished numerous times' and may have been rejected publicly. But there have been insufficiently equitable policies and practice. James Watson's views on race and intelligence appeared in 2007, arguing that Black employees and 'all the testing' show that the intelligence of Black people was not the same as ours. There was a public outcry that disgraced Watson. However, UK education policymakers 'act as if they fundamentally accept the same simple view of intelligence (as a relatively fixed and measurable quality that differs between individuals)' (243), even though they don't use the term intelligence but prefer 'ability' or 'potential'. The view of intelligence as something measurable persists, and it is necessary to refute it: 'there is no test of academic potential'. Predicted achievement is 'at best an informed estimate' based on how people with similar scores went on to achieve, the average past performance which cannot be extended to individuals who have just been tested. Test performance is not fixed, and tests only measure what people can do on particular tests on particular days, and they can be coached and their performance improved significantly. A parallel is with the driving test, which is not assumed to be once and for all, or to indicate some 'inner deficiency that can never be made good' (244). Eugenics has had a massive impact on education in the past, before it was discredited by Nazi atrocities. There is now a 'new eugenics' based on 'sorting and classifying practices of schooling'. It is found in the 'contemporary obsession with testing' to identify ability levels, and found in DFE statements about gifted and talented versus average or struggling pupils. Cyril Burt once supported a tripartite system, and this is now echoed in policies for the gifted and talented, assuming some general ability, that can be measured and that is relatively fixed. Both main political parties in Britain seem to support this idea. They would rarely want to link them to race explicitly, but the outcomes of processes do lead to racist inequity, and will lead to further 'racist patterning of educational inequality through a superficially colourblind privileging of individual effort, "talent" and "potential"' (245). In 2009, the British Government produced a policy document which talked of new opportunities and fair chances which was widely supported by a number of other departments. It talked about making the most of individual potential over a lifetime. It assumed people were 'autonomous subjects able to make their own destiny in a meritocratic market', where rewards flowed according to 'aspirations, effort and excellence'.. It was all tied to globalism [and the technological future agenda], and social justice and opportunity, defined as fulfilling potential, perhaps the most frequently mentioned phrase in the whole document. Policies included National Skills Academies and the encouragement of self-employment. Potential was assumed to be self-evident but unevenly distributed: mentoring advice and support would help low income children with potential to get into higher education. There is no equality of outcome because that '"discounts hard work and effort"'. Individual talent and potential will replace 'substantive equity' for Gordon Brown. The global recession did not lessen neoliberal policies and their impacts, but rather intensified neoliberalism. Equity is now a luxury compared with the need for greater efficiency and productivity. Meritocracy is required. Central concepts like potential are never investigated. The educational system and its labels are never questioned, nor their ability to assess '"development"' with confidence (248). It all sounds precise but it is based on 'teachers judgements and – as was wholly predictable – the outcomes are profoundly marked by race/racism'. Earlier evidence has been ignored in favour of colourblindness and implicit eugenics. There are specific implications for Ireland which is experiencing 'anti-immigrant sentiment and racist educational technologies'. [I would like to know more about these] Diversity should extend to much more than 'basic language services'. New assessment techniques will only give ' a spurious air of scientific rigour to teacher perspectives that embody centuries of racist stereotyping to hide behind colourblind rhetoric'. See also Connolly et al on setting policies for maths, and the influence of KS2 tests and teacher judgments -- there are apparent effects of gender and ethnicity especially in this large-scale statistical modelling piece |