|

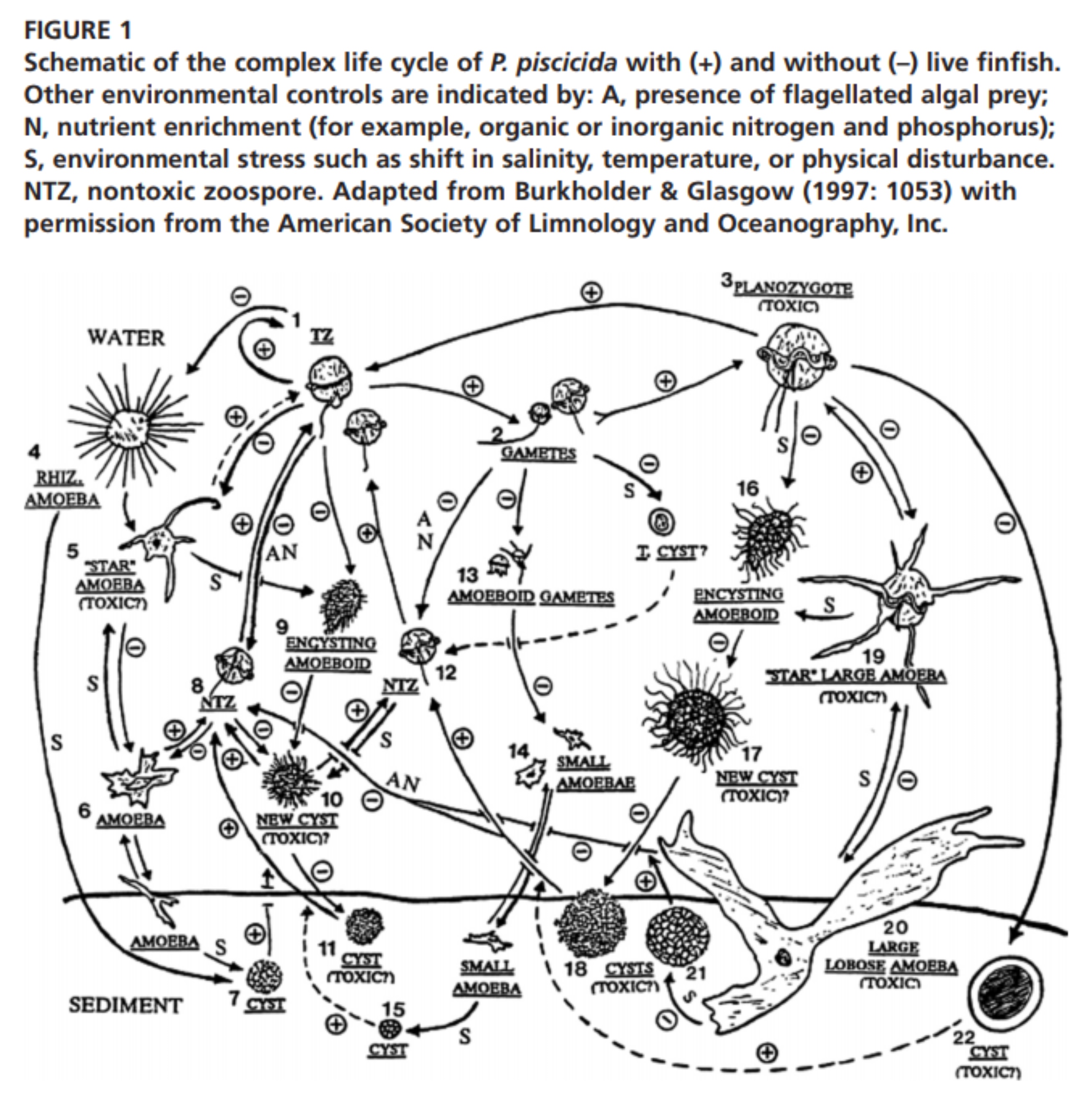

Dave Harris The abstract tells us that after nearly 2 decades, it is still unclear whether the beast is a [single?] causative agent of massive fish kills. Her own view is that this arises not from just a temporary gap in scientific knowledge, but rather from 'an inseparable entanglement of P's identities and their toxic activities', and that she is going to pursue notions of agential realism, and her own phantomatic ontology [with an obvious nod to Derrida]. It is also a commentary on how various experiments have proceeded to try and pin down some of the causals. The beast is a 'killer dinoflagellate' (276) suspected of killing 'more than 1 billion fish'. It is in one form a single celled microorganism, but it can form algal blooms, 'red tides'. Most are not toxic, but occasionally it seems to take a toxic form, hence its second name. An early study called it a phantom [innocent of Derrida?], and water pollutants were originally suspected. The stakes are clearly high because the beast became a major ecological problem and so did pollution. After two decades of research however, we can still not implicate the beast as a causative agent. Uncertainties in science have been much discussed. This paper focuses on 'the materialities of scientific experimentation' (277) and the influence of ecological and political relevance. It builds on Barad and Derrida. Temporalisation of the object is particularly important, [ the way it is realised in different actualisations, not just its conventional life history. -- A serious challenge to causality as well shall see -- Note 8 below] We should be responsible to more possibilities including multiple histories and agencies, responsibility, 'an enabling of responsiveness within experimental relatings'. The beast is apparently capable of 'discrepant enactments' and we need to grasp all of them. Scientific uncertainty seems to confine it to the separate epistemological area. The dinoflagellate is usually benign but it can metamorphose into a toxic version, emerging from sediments, attacking fish, and then disappearing. We need to take the notion of a phantom seriously here to describe these various 'ephemeral appearances and disappearances' and trace them to 'the very nature of their species beings' — hence phantomatic ontology. This is aligned to hauntology in Derrida, where spectres are neither being nor nonbeing, indicating an indeterminate relationship between past and future [in language, though I insist]. This will also help us focus on political and ethical concerns and experimental practices. It contrasts with earlier attempts to suggest 'multiple ontologies...or uncertain ontologies' for the creature. This conforms to a trend to see scientific objects as 'increasingly lively and active', with their own history or temporal order, as having a productive force. As human subjects have been displaced, there is now 'an almost exclusionary focus on the productive forces of scientific practices' [which obviously still involves humans], in Latour for example. The very production of scientific objects can have an effect, and we cannot eliminate this from our experimental practices — indeed we must be more open and responsible about it. We can leap to the conclusion that the creature is a new kind of scientific object, a phantom, lacking a specific topology, not even a'" fluid object"', changing configurations in different contexts. There is a serious challenge to the conception of time as homogeneous. Phantoms are rather like what Law and Singleton call 'a "fire object" — a generator of "links between presences and absences"' (279). They demonstrate différance, something undecided between active and passive. They become traces as in Derrida, surfacing with specific concerns. They are not empty signifiers deferring meaning until science settles it, but are '"tangentially real"; they contribute to their own materialisation' and this apparently 'makes demands on us to be accounted for'. We can study science in the making as Latour calls it, telling the story of attempts to experiment with the creature, assuming that the means of scientific understanding 'affect that which it studies'. There is no agreement that what is studied is an object or product, because the creatures 'have not achieved a stable identity'. The story is unfinished, not ending in a definite product, or victory for one particular approach — hence indeterminacy and responsibility. Scientists have argued fiercely about this creature and disputed each other's findings, sometimes with strong opinions. They are not just arguing about environmental regulations — more is at stake. Some think that the disputes show that science is at work [and will solve the problem], and that demands for public policy are distorting the search. However, 'several million dollars of federal research funding' has still left a conundrum. There does seem to be a consensus that the creature actively kills fish, and that 'excessive nutrient loadings' result in their increased appearances, but there is no proper identification yet of the creature and no understanding of the pathway of toxic effects — indeed, toxicity is so ephemeral, that we can even talk about 'the relation between "the presence of P" and "actively toxic P"'. [The connection with policy is clear] a central body set out to find the causal chain from pollution to fish deaths and recognised the need for '"sufficient certainty"— but what this meant was never clarified. Scientists were divided about whether they were trying to show whether the creature could kill fish using experimental evidence [they seem to have had a pretty simple view of causality and scientific practice. Perhaps they mostly wanted a technology?] The creature is certainly complex, neither plant, nor animal 'but can act as both' (281). It eats almost anything available in water. Changes in available nutrition 'can trigger spontaneous transformations' [an odd connection between triggering and spontaneous?]. It is not just life stages that change but the 'entire mode of reproduction'. Mostly they live as dormant cysts, but can metamorphose 'into free swimming zoospores' — they cluster together, develop '"directed movement"', double their swimming speed and start predating on fish. They might use one or more neurotoxins to immobilise the fish. During this phase they reproduce rapidly 'both sexually and asexually', and when no fish are left change shape again — some become amoebae and then turn back into 'motionless, dormant and benign cysts'. Some people have charted the life-cycle into 24 distinct stages in 'three lifeforms: flagellated, amoeboid, and encysted' [doesn't sound too indeterminate then, just complex]. However, the life-cycle is not so much a linear algorithm but 'the superposition of various, partially overlapping temporal and spatial scales that cannot be easily disentangled' [but can be disentangled?]. Which morph kills fish is still in dispute. They live in a 'multi dimensional environmental space (different temperature, salinity, organic and inorganic nutrients)' [looks like pinning down the factors again then?], But also 'multiple temporalities' [to be developed]. Schrader thinks there may be no 'way to tell where P end and their environment begins' [same with any animal?], and whether or not the environmental conditions can be 'translated into a well-defined [weasel?] spatially bounded ecological niche'. Toxic morphs do not appear as a subset or just a temporal phase. The morphs respond to various environmental conditions, including the presence of fish. 'This is not a mutual determination between organisms and a selective environment' (282). 'There is no way to tell' which morphs are "'naturally"' part of the species and which bits are environmentally induced. 'Productive or eco-logical/nomical and reproductive activities cannot be dissociated' [especially in this case?] . And '"who P are" is not only context – but also history – dependent'. Brilliant diagram on 282  They might be better described as a '" ecohistorical nexus in an environment of potential traces"'. Their life histories are not just an ensemble of interactions says a researcher, at least not in the conventional sense of a temporal framework external to happenings and with pre-existing entities [so she is heading towards Barad — but it is not at all clear why the explanation of an ensemble of interactions will not work — not if interpreted too literally and positivistically?]. It is not just normal 'context -dependent development', a 'widespread and well-established biological phenomenon on' (283), not just normal '"phenotypic plasticity"'. There is an excess [residue one might suggest]. The distinction between internal characteristics and external or environmental behaviours 'implodes'. Boundaries are not just blurred, but rather 'the entire process of boundary construction has to be reconfigured in order to account for the entanglements within P's life histories' [still asserted really]. [So we can shift rhetorically to Barad]. Intra-activity stresses the inseparability of individual agencies or subjects and objects, prior to experiments and other enactments. Outside of those 'specific material meaning making apparatuses', toxic P is 'indeterminate'. A Barad quote is cited in support [It is actually in the middle of chapter 4 from quantum physics to 'matter', not specific to P] 'There is no moment in time in which P could be captured in their entirety' [depending on what is meant by moment, the same could be said about any animal evolving over time. This assumes some positivistic capture as well?]. This means that the questions of what they are and what they do 'are inseparably entangled'[so we are building up to performance]. We could see being and doing as complementary as in Böhr — 'mutually exclusive and simultaneously necessary' this is not just an epistemological uncertainty, but 'an inherent indeterminacy' [entailed by Böhr's complementarity?]. The interacting components are inseparable in space or time, so indeterminacy extends across space and time. So '[conventional] ontology itself is put into question and hence becomes phantomatic'. [The usual notion of certainty] assumes that knowledge and object are separate, but this view 'affirms P's contributions to their own materialisations'. We can continue to ignore this indeterminacy, but it is rooted in 'P's material agency'— they react to environments but also 'coproduce and transform "themselves"' in relation to that environment (284). This is Barad's account of agency as enactment [and if we accept it] we have to take into account agency among dinoflagellates as well [as an explanation of why certain features materialise] [the beginning of an argument by residue?]. Barad offers a performative account of agency via Butler. The difference is between incomplete identities on the one hand and fundamental indeterminacy on the other [there is also a dig at Butler for assuming that there is only room for performance in the contradictions between discourses?]. If we accept that intra-action is dynamic, we have to reconfigure time and history. Agency becomes a matter of differance, 'differentiation and temporalisation conjoined' [in Derrida], leaving indeterminacy for dynamic intra-activities. As a result, we have to accept the agency of the objects being studied and cannot guarantee that research will eventually end in being able to definitively name a thing [as Latour apparently argued]. We have to reconfigure time and causality with P [only P? P partakes of quantum indeterminacy?]. P change as a response to the presence of fish, or at least their excreta. Some transformations appear only while P are actively killing fish, so their indeterminate identities and their toxicity seem connected, although it is difficult to sort out cause and effect. They are non-toxic if cultured on algae. The non-toxic ones are easier to produce in conventional experiments. Can we say therefore that P 'itself' causes fish to die? Can we distinguish toxic and non-toxic morphs experimentally, as in classic experimental procedure? This assumes of course that we can deal with objects separate from observers. For Barad, we have to consider a whole range of practices involved in an agential cut, especially those involved in experimental observation — they will 'establish different phenomena' (285), producing different materialisations [massive generalisation here, based on the weird behaviour of quantum particles and Böhr's explanation]. Experimenters should be responsible for what is excluded, what matters, so 'responsibility and causality condition each other'. How the cut is made alters the entanglement of the components. 'Responsible enactments… will have to take P's contribution to their experimental materialisation into account', their own capability to change the relation between themselves and their environment, and this will produce an irresolvable indeterminacy, which 'precludes deterministic cause-and-effect relations' [a pretty circular argument here really, if we allow the creatures to be indeterminate as a result of their agency, we can't use determinism]. We can see the implications by looking at various 'experimental enactments' [which seem to be arranged according to some notion of progress in tangling with the complexity. The summary is on 286 – 9] One early team proposed a simple life cycle with unambiguous stages. They worked with 'a typical dino life-cycle' and then applied it to P using genetic markers. There is no difference between toxic and non-toxic forms, so toxicity was considered to be relevant to the real being of P. They tried to sort out problems with their genetic markers to decide which belonged and which were just contaminations. They assumed there was a relationship between the zoospores and amoeba. The conclusions actually ended as 'evidence against P's toxicity'. The argument assumed genetic correspondences determining particular modes of reproduction, and here, 'P's material agency is erased'. They were not able to observe toxic interactions with fish, but assumed that toxicity belong to specific life stages outside the experimental circumstances. Another team used gene encoding materials in toxin-producing dinoflagellates, but could not find evidence of these within P's genome. Somehow, P were killing fish but were not toxic. They defined toxicity as some independent chemical process that you could isolate from the animal and that would act causally. The problem here, according to Rouse anyway, is that these assumptions somehow claimed to reflect natural distinctions in the real world [this might be a philosophical error rather than a procedural experimental one — did this team actually get anywhere trying to isolate the toxin?] Both teams searched for some inherent toxic property which would be a specific cause. The potential for toxicity might be seen as the result of some inherent characteristics, discoverable by research on other dinoflagellates. Again this assumes some independent existence for these characteristics, and independence from environmental circumstances. This almost excludes toxic P 'by design' (287). 'The possibility that P's doings affect their beings is simply ignored' [quite understandably in my view because it's highly counterintuitive]. There seems to be difficulty in specifying particular contexts and generalising from them. The experiments could only produce P 'as a temporal object, foreclosing the dino's ability to respond'. Going for universalistic findings also 'by definition forestalls responsibility' [again a clash between pragmatic scientific practice and philosophical anxieties about responsibility towards nonhumans?]. Unfortunately, 'it seems to be impossible to follow P around in a controlled manner and in "contaminant free" cultures while they are killing fish' (288). {So limits to practical procedures are used to hint at ontological indeterminacy? If we ever did devise a suitably controlled study, indeterminacy would disappear?], Instead, some researchers have posited the existence of persistent '"core reproductive processes", on the grounds that the zoospores seem more prevalent and more ecologically 'relevant', although there is still a danger of '"over extrapolation"' of laboratory data. Schrader says this still involves constructing a life-cycle, imposing a beginning and a uniform performance, without fish. This erases 'poly–temporality'[a philosophical concept]. Some agency remains but possible variations are 'circumscribed by specific technologies employed, severely limiting P's response–ability'. There is a hint that it is the gain in predictability that has led to this model, not an attempt to understand all the variants [there we have the clash between science and philosophy in a nutshell]. Other researchers suggest that there might be '"different versions"' of the creature, some variability in cell division. This could be Law and Singleton's '"fluid object"' where [core?] relations change in time and reshape the object 'when environmental and laboratory circumstances are altered'. This admits that scientists themselves are suggesting connections and exclusions. Further, there is a 'synchronisation process' (289) implied, but this does not explain the shift to toxicity again [apparently because it underestimates 'nutritional histories']. By excluding toxicity, we cannot explain its role in the life cycle and 'toxicity becomes impossible to affirm'. Some researchers think that this shows the inadequacy of artificial experiment — indeed, laboratory conditions seem to preclude the existence of toxic P. So both approaches offer an idea that toxic P is both a 'temporal modification' and 'ontologically distinct' from non-toxic found in the laboratory [the problem seems to be that only in the laboratory can you compare the effects of feeding them on algae as opposed to fish]. We are left with an 'oxymoron', but really it is an indeterminacy. Beings and doings 'remain opposed' in an ecological space which cannot be reproduced in the laboratory [I'm not at all sure why — why not introduce life fish into the aquarium?]. It is commitment to this 'particular mode of experimentation' that limits the findings, especially if it minimises response–ability [but how do we know that response–ability is the key omission? An argument by residue?] The problem is so difficult that a whole new genius and species had to be invented for toxic P, but this raises problems as well in terms of what the connection might be with other species and what exactly is new [this is then linked to Derrida on how new things are related to the past]. This has not stopped scientist classifying in the past, and 'no classification is innocent' [authorities cited here include Foucault as well as people in STS]. However, toxic P is not just underdetermined — they are literally 'unclassifiable as long as classification requires existence of stable properties independent of specific relations between space and time' (290). If time is a variable, classification breaks down. There is a 'politics of classification', where costs and benefits have to be assessed, but P has a 'phantomatic character… [which]… disrupts the entire logic of taxonomy' [another generalisation from a complexity to a paradigm crisis, with a particularly exciting philosophical implication — 'toxic Phantom dinos shatter the self evidence of "our" time']. We can squeeze out ambiguity as long as we leave out toxic P. To place them both in the same species involves '"two fundamentally incommensurable ontologies"' [quoting Bowker who is probably a philosopher]. The problems persist if we try and pin down exactly what toxicity is and what might cause it. There is a certain incoherence in the scientific literature, between general toxicity and specific toxicity that kills fish — an obvious implication is that it might harm humans as well if it is the first one. There is also a suggestion that general toxicity refers to a relationship, and specific to an inherent property. To ascribe the cause of a general toxic relationship to a specific producer of a toxin, in a causal way implies that 'by definition [producers] already contains its effect' [this is apparently a problem here, although I thought it was also a characteristic of haunting]. Specific toxicity is also ambiguous — whether it is stable or dynamic, again the first one implies stable causes. But the point of this paper is to try and 'affirm P's toxicity without presupposing the existence of a causal agent' [why? To 'render experimentation more response-able', so this is the philosophical goal overwhelming the scientific?] Most research on dinos follows a particular set of guidelines to establish causality — the '"Koch Postulates"' (291). A microrganism causes a specific disease if: it is present in the diseased host; it can be isolated from the host and grown in "pure culture" [where all other possible factors have been controlled]; the new growth must induce the disease again after being injected into a healthy host; the agent in the new host must be the same as the previously isolated organism. If all these are present, it can be assumed that an organism has caused disease. None of these apply to toxic P. Toxicity exists only after exposure to fish, so it 'cannot be assumed to exist before' [strange assertion really — there can be no latent toxicity?]. Toxic zoospores are only present while the fish are dying, and afterwards they transform into benign cysts. Toxic zoospores can never be entirely isolated from other organisms — 'endosymbiotic bacteria', which serve as 'functional energy reserves' and can produce nutrition photosynthetically [what an ingenious creature]. You can't grow zoospores without feeding them, which affects the 'purity' of the culture [presumably you can isolate the food and be fairly sure that it is not a factor in toxicity — this must go on in other studies, using standard laboratory cultures]. Nor is a 'healthy fish' a single organism and they often contain a 'microbial consortium' (292). Once the fish are dead, the zoospores change shape, as they do when becoming toxic [so this is a list of possible complicating factors, which may not be solvable at the moment practically — it is still an assumption to say that therefore this indicates ontological indeterminacy]. If the identity of the creature does not change, there is no onset of toxicity, so the Postulates cannot be met [yet]. 'Does that mean that causality is in principle impossible to establish?'. The toxic and non-toxic morphs 'cannot receive meaning at the same time', so 'the experimental circumstances for their enactment are complementary'. We can now see the relation between toxic and non-toxic morphs as 'différance — toxic P differ from and defer their species being' [I'm still having trouble understanding this in a nonlinguistic context]. The same problems arise with trying to study repeatability of toxic activities. One researcher [Burkholder, who seems to do a lot of work] sees toxic P as members of a whole 'toxic P complex' [which starts to look deleuzian]. Interactions with certain kinds of fish lead to toxic P. But there are in fact 'three agential types of toxic P' — active, potentially toxic or 'non-– inducible' [cannot be made to kill fish --but still toxic?]. The first two types vary in the speed with which they can kill fish, so '"time to fish death"' becomes a way to decide between the types. [I think there is a real problem here because all three types are given the same name, implying some commonality, without saying what it is they have in common as well as how they differ] Action in the field can only be inferred from repeating experimental procedures. Toxic P are defined as being able to kill fish, but it is 'inherently undecidable' (293) [not just operationally?] as to whether repeated toxicity is detectable. Again we can mystify this with Derrida — 'P's toxicity begins by coming back. Toxic P neither proceed nor follow their traces' [a note more or less just repeats Derrida on haunting — just a fancy way of saying that we are not sure if the same creatures infect once or reinfects. I admit that this raises the problem of 'the same', but I don't see that is specific to this creature, and that we could get all Heraclitan about dog bites]. The problem of connecting laboratory results to field results is seen as 'the indeterminacy between "past" and "future" in P's toxic activities' [that is we have no specific causal chains joining them]. We can turn to Barad on causality as 'iterative intra-activity' [no doubt, but must we?]. Component parts for a phenomenon can be differentiated only after 'a complete specification of the experimental (material and discursive) circumstances' [this is of course ideal]. Only then can the effects on fish receive meaning as effects , because there might be as yet underresearched variables [precisely]. Toxicity is one of those Barad/Rouse 'repeatable patterns' which can gain meaning only from intra-actions [I understood this differently — that we get repeatable or objective patterns only by intervening via apparatus]. However repetition is difficult in the case of P, who are both context and history dependent. We must therefore [leap to the most extreme possibility] see this as entanglement between bodies and environment and past and future, and neither can 'be resolved at the same time' — and if we can't impose an objective time sequence differentiating bodies and environment, the only way to relate them is through what she calls 'temporalisation — the [agential] establishment of a relation between "past" and "future"'. [This is the key]. There have been 'bioassays' trying to see whether P that kill fish in the lab are also toxic in the field — this would show whether short separations from fish would influence future abilities to kill them. It is already known that toxic zoospores turn into cysts, but killing apparently resumes within 4 to 9 days. Non-toxic lab specimens took longer to become lethal — 6 to 8 weeks. This indicates that P have 'a "biochemical "memory"' retaining the effects of recent stimulation by fish. However, this memory is not intrinsic, located in the organism and genetically determined. It does not proceed activity with fish but rather 'conditions their intra-activity', not recalling the past but 'recreat[ing] a past each time it is invoked' [the accompanying note 25, 302 is interesting because it cites a remark about human memories who can also create some sort of new past via recollection and once causes and explanations are attached to it. I think this is a kind of reverse anthropomorphism]. Burkholder et al observed morphs that looked like zoospores in a sample of water collected from ministry while fish were being killed. Healthy fish were introduced. If they died as well, we might be able to see the zoospores as actively toxic. Some zoospores can then be isolated and cultivated by feeding them algae, then replaced with healthy fish, 'accompanied by a consortium of other microbes' (294). Then time to fish deaths can be observed. Actively toxic creatures 'have to be continuously fed with fish', and not dead ones. Activity seems to depend on zoospore population increase and that depends on how frequently fish are replaced. However, P's memory of previous exposure to fish also affects the behaviour. For Schrader, this means that the relation between toxic P and fish 'is not causally fixable at any moment in time' [presumably, this means that some variance was unexplained, and the hunch is that it is down to some mysterious memory in P?] Repeated iterations introduced new complexities — some fed on algae produce zoospores before being exposed to fish. The search was launched for factors which might explain why fish are not killed in certain controlled experiments involving toxic P. However, as soon as a factor is suggested as a causal that switches on fish killing, toxic P change both in number and kind. It seems that repetition of the experiments continually 'modifies the boundary between the putative fish killer and its environment'. We could isolate the creature from its environment 'only if repetition would not alter this boundary' The result seems 'hopelessly circular', defeating even Barad's notion of cause, because the P does not stay the same through the iterations. Derrida apparently suggest the same for 'all kinds of objects' [again I can see this for linguistic objects]. We might have to change our preconception of time, no longer assuming that it consists of the passage of discrete entities, or, for Derrida '"successive linking of presents identical to themselves"' (295) [Straw man? I think the confusion here is what stays present and what changes — how much has to change before we can assume that the present is not being reproduced?]. We might use Derrida's term '"iterability" [which looks very paradoxical and gives an active role to a process of 'temporalisation', which is presumably akin to materialisation]. The argument seems to be that processes must be iterable to produce any kind of mark or object. Barad prefers to talk about causality from cutting things together and apart [to locally resolve entanglement]. Cutting apart means differentiation, for example between object and apparatus, cutting together extends the entanglement and becomes temporalisation because traces or memories are connected as well. These new connections mean a new phenomenon, as 'the condition of possibility' of its appearance. We can replace divisions between the original and the new, because temporalisation is an extended process. It guarantees identity. However, it also precludes causality because there is no beginning or discrete event which produces the present [not even birth or death?] What the Burkholder experiments are showing is not the complexity of causality but rather 'a temporal pattern', relating first and second exposures to fish death. These are related apparently 'under specific environmental conditions such as water temperature, salinity, pH, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphate content and so on' [which look awfully like conventional causes to me]. Together these make up not an unambiguous cause but environmental conditions which permit continued action [ie still an excess or residue?]. Unambiguous cause could only be shown if actively toxic P in the laboratory were connected to particular fish kills in the field, and in a repeatable way. This is better described as temporalisation of the toxic phenomenon [for philosophical reasons again?]. If we're going to do this relation between active toxic P in the lab and killing of fish in the field, we must make sure that both environmental and experimental conditions are not fixed by some accepted arbitrary procedure but are 'sufficiently constraining, simulating field conditions… Flexible enough to continue fish killing over time' (296), and this can only be done by allowing for memory of previous exposures. In turn this means that the conditions are involved in 'an interactive synchronisation between P's memory and the frequency of the fish replacement', and this will better explain 'the temporal variability of P's response to fish in every iteration'. However, we can't talk any longer about causes proceeding effects in linear time, in homogeneous time. Agential differentiation 'must be accompanied by temporalisation — an interactive process of synchronisation' [crucially over time]. Synchronisation involves 'temporally heterogeneous activities' being reconstituted, not tests of simple determinism by varying environmental conditions. We must see toxic activities in the lab as 'the future trace of a specific "past" fish kill in the field', something 'inherited', not actually reproduced in the laboratory. This inheritance becomes active under particular environmental on the experimental conditions [even more staggeringly, these conditions actually have to make 'experiments repeatable'. It is not that repeatable experiments might show this memory, but they have to constitute and activate it somehow — does the P know it's taking part in an experiment?] [In a slightly more conventional way] we have to adjust environmental conditions to allow for continued toxic response to fish in such a way that they 'become conditions of possibility' for killing fish in the field. Successful repetition of an experiment can ensure this. Schrader still insists that this only happens if we pay attention 'to the agencies of the object of study — the maintenance of P's response-ability'[which might just mean that we have to do go beyond the possibilities of formal traditional experimentation to observe what the beast is actually trying to do]. These must also be seen as 'part of the objective referent'. The mystery of the failure to identify P in a conventionally stable way can be explained by including this temporal connection. Again, in the most dramatic way 'P's memory does not change in time, but changes time itself' (297) [just crazy, and perhaps intended to sympathise with Haraway's notion of a chronotype, cited just below, which apparently refers to the topos bit as 'the site of engagement or a matter of concern'.As usual, I suspect a lot of the mystery would disappear if we just rephrased that sentence — 'if all this stuff about memory is right, we will have to rethink the conventional notion of time, especially if we define it as restrictively as Derrida does, as a series of 'presents'. But why not check to see if we can't explain 'memory' first'] So there is no real missing link between the phases, but rather a process of iterative temporalisation. To philosophise, we can think of toxic P as having 'always already' been capable of killing fish [or in simpler terms, that toxicity exists as a potential]. There is a 'Toxic P Complex' indicated by this continued ability to change form and behaviour [deleuzian terminology would be useful here, but Schrader wants to persevere with Derrida to call this 'phantomatic' being and to quote the great man to suggest that repetition is always important to the appearance of phantoms, that we cannot capture their comings and going scientifically even with better methods, and as a result, phantoms challenge 'the "synchrony of the living present". Does this help?]. Phantoms do leave traces. This somehow 'demands' to be accounted for by us. If we are being responsible, we must do 'enabling of responsiveness' within particular relations, and to accept the idea of an extended phenomenon. Only then will we get the experiments to work [so has this been put into practice? How would you put it into practice ? What's the difference between doing this and just thinking up new variables that might need explanation?]. In this way, the enactment of toxic P 'is thoroughly entangled with what comes to matter', with obvious relevance for environmental politics. [Instead of all this philosophy?] some scientists have criticised the technique of the bioassay for failing to penetrate ambiguity, and the particular role of the environment or even '"the complex microbial community"'. There is a suspicion that further interactions with more bacteria might be important. So far, the experiments have not even been able to say whether it is the toxin that kills the fish or physical attack by the dinos. These are interesting, but still do not challenge causality sufficiently [the suggestion is that 'the matters of concern are different' (298) — indeed, scientific versus philosophical concerns?]. If there are important implications for assessing human health risks and not just fish, the bioassays are inadequate. They have not even explored the implications for human health after 'massive fish kills'. Again Schrader wants to argue that the kind of causality at work is responsible, together with a tendency to blame uncertainties [so preserving uncertainty risks human health, while scientist dither — but does Barad stuff lead to better policy or safer water?]. Chasing after uncertainties or gaps in knowledge still operates with an independence between establishment of the facts and the experimental questions asked [which seems perfectly reasonable — why philosophise when there are urgent questions to decide?]. But evidence in the cases discussed should be seen as 'part of the experimental apparatus', and we should focus instead on the '"how" of their [P's] enactment'. The different enactments 'are not a matter of epistemological uncertainties or opposing views'. Nor are the different versions of toxic P just incomparable. Instead 'various laboratory practices have enacted different kinds of objects' — the 'atemporal genetic P', the fluid object, and the Phantom. These practices show different degrees of responsibility, different ways to manage P's responsiveness. We're not just doing epistemology, not even accepting multiple ontologies, but looking at spatiotemporal relationships themselves and how experimental determinations cut them [human beings do have an enormous responsibility after all, because they can even 'create' toxic forms?]. We should see earlier attempts to explain as really denying causality as a form of inheritance, not accounting for the full response-ability of the creature. We should grasp instead inheritances to explain the transition from field to laboratory. We can also think of a particular scientific form of inheritance, where we take Koch Postulates, not to reject them or literally follow them, but to see them as 'materially reconfigured — that is, inherited' (299) [quite a different notion depending on familiar processes of human memory and adaptation]. We can affirm entanglement in P's beings and doings [the same as quantum entanglement?], 'ontological indeterminacy'. This provides 'the very condition of possibility for objective and responsible scientific practice' [danger of circular definition here if responsible scientific practice as a condition of possibility for ontological indeterminacy?]. Members of the Toxic P Complex are 'phantomatic; their being remains "to come"'. The relationship between P's being and the practice of responsible objective science 'must be reconfigured in every intra-act through specific matters of concern' [but will it ever lead to a technology?]. With phantoms, not everything can be brought to presence, but there is not just a simple pattern of presents and absences. Instead 'they are neither present nor absent… "Non-contemporary" with themselves' for Derrida, or complementary for Böhr [example of argument by two very different authorities really]. The embodiment of phantoms shows their traces, but these remain dynamic rather than repetitive. [We can directly now substitute P in the sentences] 'P's movements are reconstituted through inheritance'. We have to remain responsible towards their past even if it will never be present even in the future, as a repetition or reproduction [Derrida again]. The Phantom is 'im/possible', and we can only determine its form 'here and now'. Responsible scientist do not just follow established notions of good practice, or attempt to develop some cutting-edge [within an accepted paradigm]. They should instead open up possibilities for different sorts of responses, by being responsible to the past and future. We should see objects and agencies of observation as entangled, and past and future in scientific practice as entangled as well. We can't just see the past as something already known [straw man if this means 'fully known'], but instead as a matter of inheritance, 'to which not only humans contribute' [author's message]. Scientific progress does not just mean an ever-increasing amount of human knowledge. If we give micro organisms a role, we are not absolved from our own responsibility to contest and rework our own boundaries — agency should extend to include changing particular practices, or, in Derrida, a fundamental interruption of '"the ordinary course of things, time and history here – now" ' Note 1 says that many ecologists are still not convinced and believe that they can track the effects of altered environments. Note 2 says some human health impacts have been reported during large fish kills. Note 6 p.300 is interesting in saying that we can link these remarks about science to notions of capitalist efficiency in production: 'in lieu of human agency, power and capital have become self moving agents' [but this is still ideological?]. There may also be links with the idea of movement 'inherent in narratives of scientific and capitalist progress. Note 7 says that the argument is compatible with Latour on the arrow of time moving from simplicity towards increasing complexity. Note 8 quotes Kirby V saying that just citing realisation as the sole process 'reverses the logic of causality but does not contest its linear discriminations of difference as separability'. Note 12, 301 sites an authoritative 1998 report that says that nutrient loading reduces the risk of toxic outbreaks, but that there is not enough information at the moment 'to quantitatively determine causal relationships with confidence' [so it is this full causality that is being doubted]. Note 16 makes another exaggerated claim that material agency is not just outside the human realm, but 'displaces the very distinction between human and nonhuman agency' [that is makes us rethink our earlier definitions]. The same note points to a difficulty with using human language to explain what's going on — the 'agency' of P, for example does not mean that the dinos are pre-existing subjects or objects, nor is there specific nonhuman agency [the boundary is displaced as above]. And above all 'The same holds for the experimenting humans' — classic reduction of human agency to make it compatible with nonhuman?. Note 20,p.302 says that epidemiologists stopped thinking about single causes and thought instead of a web of causation, but single causal agents are popular again, promising to be identifiable by genetic markers — 'the future of epidemiology lies in the search for genetic markers' one epidemiologist apparently said. Note 25 is the reverse anthropomorphism I have mentioned above. Note 26 says we have to know about environmental conditions in order to demonstrate a link in various separate experiments, but, none of them so far explains the particular emergence of toxic P. Note 27 says that matters of concern are not just intentions of particular scientists nor even 'solely human affairs'— 'they neither proceed nor follow matters of fact, but rather condition them' [pass -- investigation follows human interests?]. Note 28 comes clean by saying that much of this argument unsettles the fixed difference between humans and animal others, which limit conventional notions of responsibility to the other. barad page |