Notes

on: Deleuze G and Guattari, F

(2004) A Thousand Plateaus, London:

Continuum. Chapter 1 Introduction:

Rhizome

Dave Harris

Summary

Any system of classification (trees

or tracings), academic approach

(psychoanalysis) or conventional narrative

(in normal books) that rigidly applies fixed

categories misses out on a lot of complexity

and only takes snapshots of processes

They

wrote this collectively to show how

individuals are (a) pretty irrelevant and (b)

merge into each other. They used ‘clever

pseudonyms’ as well (3). I wonder who

‘Professor Challenger’ might be in ch. 3? [see

below] A clue: it is someone who rambles on

using examples from many different disciplines

even though he admits he is not an expert in

any of them, and whose audience tend to walk

out in despair after his rambling asides).

[Actually, he is a character in A Conan

Doyle's stories -- an boringly aggressive

adventurer] They only keep their own

names because want to be imperceptible (see

ch.10 ) because it is nice to be an ordinary

person sometimes [luvvie!]. The book is

actually an assemblage or multiplicity so it

is unattributable [the old death of the author

stuff, p. 4 --must get a plagiarising student

to try that one]. This book is a rhizome not a

tree structure, a little machine, and it is

about ‘multiplicities, lines, strata and

segmentarities, lines of flight and

intensities, machinic assemblages and their

various types, bodies without organs and their

constructions and selection, the plane of

consistency and in each case the units of

measure’ (5).

In

writing a book like this, 'The multiple must

be made, not by always adding a higher

dimension but ...with the number of dimensions

one already has available -- always n-1 (the

only way the one belongs to the multiple:

always subtracted). Subtract the unique from

the multiplicity to be constructed: write at

n-1 dimensions...A system of this kind would

be called a rhizome' (7). [I added this bit

later after reading a reference to n-1 in an

educational commentary -- the author -- Gale I

think -- saw this as trying to remove oneself

from one's writings. I see it, after reading

DeLanda, as a commentary on a multiplicity as

a complex set of singularites and vectors,

where all this is hidden in actual events.

Writing at n-1 then means getting behind the

apparent self-sufficiency of the actual event

or object, stepping back from the concrete

detail].

‘Becoming’

– probably just a long winded and hyped up way

of saying the above, that complexity and

potential should be allowed for, as a kind of

familiar anti-positivsm [aimed at Hegel's

separation of thesis and antitheses, I have

since read] . Hence we need to work on

understanding people on the plateaus (not at

some mythical beginning or imposed end).

Example of becoming in Ch 1 – Little Hans, who

was oppressed by Freud in the familiar way

(reduced to Oedipus etc) and not allowed to

have heard his attempt to build a rhizome

(expressed as lines connecting locations like

his house and the street etc – because D&G

were in the middle of some blurb about the

difference between maps and tracings). Then

this: ...’how the only escape route left to

the child is [surely as] a becoming-animal

[is] perceived as shameful and guilty (the

becoming-horse of Little Hans, truly a

political option)’ (16). I find this just

baffling. Freud did impose his usual stuff on

the kid, and Hans was tormented by wanting to

find out about sex while being threatened by

his father if he explored his mother (and by

his mother who threatened to chop off his

widdler if he masturbated). But horses only

came into it all by accident really [maybe

this contingency is common]-- they had big

widdlers and they did odd protosexual things

like falling over, drumming with their feet

(an infantile image from a primal scene,

although his Dad denied it) and hauling large

boxes/wombs. Hans wanted to play with the

street urchins in the yard opposite his house

– discouraged no doubt on class grounds. But

nowhere does Hans really want to be like a

horse – like his father certainly, as his

final fantasy showed. How on earth was he on

his way to ‘becoming’ a horse in any sense?

Why would any schizoid politics of becoming

have helped the poor little sod who was phobic

(of horses, as it

happened)? Hans is being forced to play a part

for Deleuze and Guattari here – to get more

schizy to help make their point. It is just as

repressive as making the poor little lad act

out the Oedipal drama. It is an example of the

dubious kind of subjective liberation that

awaits if we plunge into the world of D&G

--free yourself from all constraint is a great

idea for professional intellectuals but for

normal people it would lead --to anomie?

Other

point: have we ditched the whole array of

theoretical stuff developed in Anti-Oedipus?

Machinic breaks/flows have now become

rhizomes? Where are the conjunctions and

disjunctions? The

molar and the molecular, subjugated and

subject groups? Desiring machines are

mentioned and there is a whole chapter on bwo

which I will get to, but it all seems far less

obsessively detailed than AntiOedipus [boy, was I wrong about that!].

Has Deleuze recovered from his delirium? I

think any reader should start with this volume

and leave the more obsessive one for later,

and then only if you are particularly

interested in postructuralist revolts in

French academic life and how they overthrew

the dominance of Marx, Freud and

Levi-Strauss: Foucault explains it all

tersely and well in the Preface (and in his

essay in Power/Knowledge)

OK, so I have revisited, after reading a lot

more of this turgid bloody book, and

tried a more detailed set of notes. I am still

converting bullshit into Portsmouth, however:

Books are composite without an object or

subject, influenced by the exterior relations

of its subject matters, with both lines of

articulation, but also lines of flight etc.,

in an assemblage. The book is a

multiplicity [as well?]. One side of the

assemblage faces the strata, but the other

side faces a body without organs, which

preserves open access, not limited by being

attributed to a subject, 'causing asignifying

particles or pure intensities to pass'.

Several things are found on this body without

organs according to which lines are followed

and how or whether they converge on or are

selected by a plane of consistency. The

aim is to produce a book which talks about

something and simultaneously about how it is

made. There is no object. As an

assemblage, the book relates only to other

assemblages and other BWOs. There is

therefore nothing to understand (from an

external reference system like a theory) , no

signification [no external reference],

although there are relations with the outside

[which shape some of the relations

inside?]. The book is therefore a

machine, related to other machines like war

machines, love machines, and ultimately to an

abstract machine. This book is clearly

plugged into a literary machine which has

produced other texts, hence the quality for

which they have been criticized - 'over

quoting literary authors' [which helps us see

the self defensive nature of this whole

explanation]. Literature itself is an

assemblage, not an ideology - 'There is no

ideology and never has been'(5) [that is, no

general theory of ideology, like the rather

reductionist version of Marxism they operate

with].

They want to talk about 'multiplicities,

lines, strata and segmentarities, lines of

flight and intensities, machinic assemblages

and their various types, bodies without

organs...the plane of consistency, and in each

case the units of measure' (5) [intensive

units that is of course]. So their

writing is quantified [no doubt a response to

another criticism?], and sets out to measure

'something else'. It is not about

signifying, but rather offers 'surveying,

mapping, even realms that are yet to

come'[that is, mapping the whole of reality

including the virtual].

We often find a tree structure in classical

books, lending it to some natural or organic

qualities, but also linking it to

[interiorizing or internalizing] strata.

These books often demonstrate a binary

structure - 'the One that becomes two'.

Of course, this is not a natural structure at

all, and it already separates out nature and

art. Binary structures are not improved

even by dialectic. However, we do not

always find binary divisions in nature, as

with ramifying systems of roots. Thought

would do well to examine these natural

structures. However, even advanced

disciplines like linguistics retain this tree

structure [as with Chomsky and his grammatical

trees]. The sort of discussion of

multiplicity that we find involves

ramifications of an initial unity, a series of

objects. A similar model involves a

circle of objects around the unity, each

offering 'biunivocal' forms of communication

[sequential monologues]. Even if we

change the model slightly to consider

ramifying taproots, therefore we will still

not be able to understand multiplicity.

Tree structures also dominate psychoanalysis,

structural linguistics, and information

science.

We might consider a slightly different kind of

root -'the radicle system or fascicular

root'(6), which offers a multiplicity of

secondary roots. We find this kind of

model in our culture, apparently offering a

more extensive totality, but still with

'comprehensive secret unity'. An example

here is the W. Burrough's 'cut-up' approach to

texts, folding one text into another, adding

dimensions to text by folding.

Apparently fragmented work can still be seen

as offering some total insight. Modern

conceptions of offering series to produce

multiplicities reproduce a linear direction

for one series with a unified total collection

of series in a circular or cyclic

dimension. This still restricts the

notion of a multiplicity by specifying a

reduced set of laws of combination: we can see

this in the work of Joyce which although

rejecting linear unity, still preserves cyclic

unity; Nietzsche's aphorisms, similarly, still

invoke 'the cyclic unity of the eternal

return'[I thought other work denied this was a

cyclic unity]. We still have dualism,

notions of a subject and object, a natural

reality and a spiritual reality, where a unity

is dissolved in the object, only to triumph in

the subject [that is, imposing some sort of

subjective unity in thought or spirit].

This is a bad development, because the subject

then finds itself in some sort of relation of

ambivalence or over determination, something

that always exists outside the object, while

the world itself 'has become chaos'. We

find this in books which also offered this

image, somehow copied from the world, both

fragmented yet held together by some higher

unity.

We have to do something quite different if we

want to really get to a proper conception of

multiplicity: 'The multiple must be made'

(7). Strangely enough, we do this not by

adding dimensions to reality, but subtracting

them: 'always N-1 (the only way the one

belongs to the multiple: always

subtracted). Subtract the unique from

the multiplicity to be constituted'[in other

words, do not try to focus excessively on what

is unique, but try to look behind it to see

how unique objects are actually produced by

multiplicities, together with other unique

objects, even if they look quite separate from

the point of view of empirical reality].

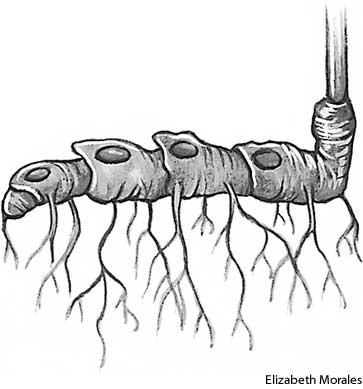

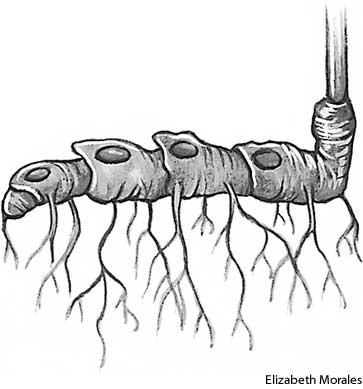

'A system of this kind could be called a

rhizome', a subterranean root, not like the

other roots we have considered [taking the

multiplicity here to exist 'beneath' empirical

reality]. Using this definition, we can

move away from the normal notion of bulbs and

tubers: all plants might seem to have these

underground connections, so might animals:

'rats are rhizomes'. Rhizomes can

proliferate on the surface in all directions,

or be concentrated into things like bulbs and

tubers. Both nice and nasty things can

be seen as rhizomes, 'potato and couch grass,

or the weed'.

Let us try to convince people further

[evidently, people were pretty unconvinced

before]. If we consider this abstract

notion of a rhizomes, we can see that any

point on it can be connected to any other

point or thing 'and must be'. We are

moving away from points which turn into series

through dichotomies on single

dimensions. Not all of the points on an

abstract rhizome corresponds to linguistic

features or conventional signs. We are

considering other kinds of semiotic chain and

other kinds of coding as well: 'biological,

political, economic, etc.'These use different

'regimes of signs'[of which more later], but

also connect things with different statuses

[for example gases of different

temperatures?]. Together, these

semiotics systems produce 'collective

assemblages of enunciation', functioning

within machinic assemblages (8). It is

not just a matter of detaching regimes of

signs from objects [to study them in the

abstract], since even explicit communication

refers to something implicit like types of

social power, or 'particular modes of

assemblage'. We see this by examining

Chomsky and his argument for well developed

grammar as an abstract quality: we want to

insist a power relation is involved [discussed

much further in the chapter on sign

regimes]. [As we will argue] Chomsky's

approach is not abstract enough, because it

does not discuss the abstract machine that

connects language to assemblages of

enunciation and to micro political struggles

over language.

By contrast, 'a rhizome ceaselessly

establishes connections between semiotic

chains, organizations of power, and

circumstances relative to the arts, sciences,

and social struggles', connecting diverse

acts, not just linguistic ones but gestural

and cognitive ones. 'There is no

language in itself'[that is, no abstract model

existing independently of pragmatic uses of

language, enunciations]. Trying to find

internal structural elements is like searching

for conventional roots, avoiding what people

actually do with language. The rhizome

method fully includes these other dimensions

and registers, and language is therefore

'never closed upon itself'.

We must consider all complex substances as a

multiplicity, breaking any relation to a

single origin, subject or object, fundamental

image or picture of the world.

'Multiplicities are rhizomatic', and we can

use this notion to criticize 'arborescent

pseudo-multiplicities'. There is no

fundamental unity, no subject or object, only

'determinations, magnitudes, and dimensions'

(9). Changes in those determinations and

dimensions only occur when the multiplicity

itself grows. There is no underlying

control by an artist or puppeteer, but rather

'a multiplicity of nerve fibers, which form

another puppet in other dimensions connected

to the first'. If we think of some actor

as pulling strings, we must complicate this

picture by remembering that 'the actors nerve

fibers in turn form a weave' [there is no

coherent actor or subject fully separated from

outside influences]. As multiplicities

extend [and condense?] their dimensions into

an assemblage, they change their nature, but

there are no defining points or structures of

the kind you find in trees in the rhizome,

'only lines'.

This sort of conception makes us see music

quite differently as a connection of lines

between musical points. Even the normal

conception of numbers changes if we see them

as multiplicities, not just stages in a single

dimension, and this helps us see that there

are many units of measurement. A power

struggle can lead to the imposition of a

unity, insisting on the importance of the

signifier, or constructing particular

privileged subjects [again discussed more in

the chapter on different regimes of signs],

and this often leads to the notion of some

fundamental One, or for a 'pivot-unity'

[privileged sets of biunivocal

relationships]. This unity has to posit

itself outside of the system however, and to

engage in 'overcoding', from outside.

This never takes place with rhizomes or

multiplicities because there is no extra

dimension outside the elements that constitute

it. In this sense 'all multiplicities

are flat' [never controlled by something

outside them in a hierarchy]. This

provides us with the concept of 'the plane of

consistency of multiplicities', even though

the plane itself can increase as more and more

connections are made on it. There is one type

of outside to a multiplicity, 'the abstract

line, the line of flight or

deterritorialization' (9-10) [otherwise

multiplicities would never change]. The plane

of consistency is also outside particular

multiplicities. Multiplicities happily

fill a finite number of dimensions with no

supplementary dimensions until a line of

flight arises, connecting multiplicities on a

plane of consistency. Multiplicities are

'asignifying and asubjective' as argued above.

An ideal book would lay everything out on a

plane of consistency -'lived events,

historical determinations, concepts,

individuals, groups, social formations'

(10). Kleist is admired for developing

writing of this type.

Multiplicities are not internally divided into

structures. Rhizomes [of the garden type

this time I assume] show us the possibilities

of reforming, starting up again even if

cut. So do ants , 'an animal

rhizome'. Rhizomes do show 'lines of

segmentarity' [concrete, actual lines] which

can be stratified and territorialized, but

they also have 'lines of

deterritorialization', and 'the line of flight

is part of the rhizome'. Artificial

attempts to polarize them, say into dualities

will never work. At the same time, lines

of flight can be restratified, restrained by

power, which might assign some authorized

signifier, or understood as the attribute of a

subject. This danger is always present,

as 'microfascisms just waiting to

crystallise', so it is naive to divide the

characteristics of the rhizomes into good and

bad, unless we recognise we are making a

selection, and we need to constantly revisit

it.

As an example of the relative

interrelationships of deterritorialization and

reterritorialization, let us consider the

orchid and the wasp [sigh]. Both swap

processes of de and reterritorialization as

they interlink [the orchid deterritorializes

by forming its image, and the wasp

reterritorializes on it , and lots more

tedious interweavings take place, 11].

Wasp and orchid are heterogeneous but they

form a rhizome. Their actions look as if they

take place in one dimension, but several

dimensions are in fact are involved, and not

just simple imitation or capture of code - the

'becoming-wasp of the orchid and a

becoming-orchid of the wasp'. As one

becoming develops, patterns of

deterritorialization and reterritorialization

interweave and increase

deterritorialization. It is not just a

matter of resemblance, rather 'an exploding of

two heterogeneous series on the line of

flights composed by a common rhizome'.

No signifying is involved. The process

has been described as '"aparallel evolution"

of two beings that have absolutely nothing to

do with each other'. We might have to

consider a number of evolutionary schemes in

this light, and abandon the old tree

metaphor. Once we have adjusted our

perspective, for example, we can see aparallel

evolution connecting the baboon and the cat

[apparently], again making the point the two

animals do not have to copy each other.

Another example might be the transfer of

genetic material through viruses offering

'transversal communications between different

lines' (12). This reminds us of the

importance of molecular or submolecular

particles - flu is a rhizome not a classic

evolving disease. 'The rhizome is an

antigenealogy'.

Consider the book as in aparallel evolution

with the world: it deterritorializes it, but

the world reterritorializes. Books do

not mimic the image of the world, but form a

rhizome with it. Crocodiles do not

imitate or reproduce their surroundings, nor

do chameleons. [And then a really silly

section about the pink panther, which paints

the world pink and thus becomes-world, aiming

at imperceptibility, refusing to

signify]. [Even non-rhizomatic in

the normal sense] plants form rhizomes with

something else, like the wind or animals or

human beings. We should always follow

rhizomes until we get to the most abstract and

tortuous connections. The lines of

flight will eventually lead us to the abstract

machine operating on the plane of consistency

[homely quote from Castenada about the way

seeds are dispersed]. Music is another

example, capable of overturning its own codes,

so 'musical form…is comparable to a weed, a

rhizome'.

Rhizomes

have no 'genetic axis or deep structure'(13),

no central pivotal point, no elements to be

united by subjectivity. At best, these

features produce 'principles of tracing' and

reproduction of the structure. In

classic psychoanalysis, the pivotal object is

the unconscious that becomes crystallised into

various complexes, developing along a genetic

axis, and 'distributed within a syntagmatic

structure'. The point is to maintain

some sort of 'balance in intersubjective

relationships', relying on an unconscious that

is already there to be uncovered, or

traced.

Rhizomes offer 'a map and not a tracing'[this

reminds me of the debates between advocates of

behavioural objectives and knowledge

structures - the former highlight the

particular favoured route through the

territory, while the latter offers the whole

map]. [NB they also talk of

'decalcomania' here -- an art form where

things are stuck on to the surfaces eg of

pots]. It does not just reproduce the real

though [unlike real maps then], and links

fields, undoes blockages on bodies without

organs, opens onto a plane of

consistency. Their kind of map is 'open

and collectable in all of its dimensions', and

you can move along it in various ways,

constantly modifying your route if you

wish. Individuals, groups or social

formations can establish routes. Maps

can appear as works of arts, political actions

or meditations. One of its most

important aspects is its 'multiple entryways'

(14), and burrows inside it [like those of the

pack rat] can be lines of flight or living

spaces on strata. Maps stress performing

rather than just competence. Thus

schizoanalysis refuses to develop any

predestined tracing. Conventional

psychoanalysts like Klein operated with ready

made tracings stemming from Oedipus [in the

case of Little Richard], and the child's

performance was misconstrued. Although

she identified particular stages like

attachment to part objects, these are really

'political options for problems', constraining

children and presenting them with impasses.

Is this just not another dualism between map

and tracing, one being good and the other

bad? Obviously, maps can produce

tracings, just as rhizomes intersect with

roots. All multiplicities have strata on

which conventional social processes like

mimesis, conventional subjectivity, or power

takeovers can develop. Even lines of

flight can reproduce the formations which they

intend to dismantle. But the reverse

process is the key to method - put the tracing

back on the map. This does not reproduce

a map. Tracings are selections from

maps, images of maps that domesticate rhizomes

'into roots and radicles', stabilizing

multiplicities by signifiance [NB] and

subjectification, and ending by just

reproducing itself. If you collected a

series of tracings, you would only get all the

problems reproduced and imposed on the map -

'impasses, blockages, incipient tap roots, or

points of structuration'(15).

Conventional psychoanalysis and linguistics

has produced a number of tracings, but we see

the consequences, say in the case of Little

Hans [I am glad he's back, I have missed him],

whose map was broken and blocked, who had

shame and guilt 'rooted' in him, producing his

phobias. Freud charted some of the map,

but then imposed his views of the family on it

[he manage to 'project it back on to the

family photo']. Klein did the same for

Little Richard. Once your rhizome has

been channeled, 'no desire stirs; for it is

always by rhizomes that desire moves and

produces...by external, productive

outgrowths'.

What we should have done is help Little Hans

build a rhizome linking the family house, the

line of flight into the street and so

on. Professor Freud imposed a signifier

on his desires, producing only 'a

subjectification of affects'(16). Hans's

option was a 'becoming-horse', 'a truly

political option', but this escape route was

associated with shame and guilt. We need

to reconstruct the whole map, with Freud's

tracing placed on it.

We can do this on a group scale as well,

placing 'massification, bureaucracy,

leadership, fascisation etc.' on a group

map. This will also help us preserve

lines which continue 'to make rhizome in the

shadows'. Apparently, Deligny did this

with combining the maps of several autistic

children. It might be possible to enter

such a map through particular tracings,

'assuming the necessary precautions are

taken', like avoiding 'any manichean

dualism'. We often do have to pursue

tracings to dead ends to uncover the maps of

the unconscious, exploring 'rigidified

territorialities that open the way for other

transformational operations' [as in Chaosmosis]

. Alternatively, we can follow a line of

flight from the start to demolish strata and

roots, and make new connections. Of

course there are root structures in rhizomes

and conversely, and there is no theoretical

analysis to distinguish them, only pragmatics

to compose multiplicities or aggregate

intensities. Even accounting and

bureaucracy can turn into rhizomes, 'as in a

Kafka novel'. Intensive traits, like

hallucinations or play with images can

challenge 'the hegemony of the

signifier'. Childish gestures and play

can extricate kids from tracings, like that

'dominant competence of the teacher's language

- a microscopic event upsets the local balance

of power'. Even Chomsky's trees

can be turned into a rhizome. The trick

is to take stems that seem to be roots, and

'put them to strange new uses' (17). We

should celebrate the rhizomes and not the

tree. Amsterdam is 'a rhizome city'

connected to 'a commercial war machine'.

Brains are not ramified into dendrites, and

messages can leap across the structures,

making the brain itself a multiplicity, a

probabilistic system, grass more than

tree. We can see this with studies of

memory, and reinterpret the differences

between long-term and short term memory as

being the difference between the tree and the

rhizome respectively. This helps us

produce and validate 'the splendour of the

short term Idea'[ as in spontaneous or

delirious writing?]. The traces of

long-term memory are continually affected by

the shorter term actions.

Tree models produce their own models of the

multiple as 'a centred or segmented higher

unity' (18). They feature different

sorts of links, 'dipoles', sometimes running

from bottom to top, sometimes taking the form

of radiating spokes. No matter how

prolific these links are, we never get beyond

the old binary system and 'fake

multiplicities'. Hierarchy remains, as

do 'centres of signifiance and

subjectification'. This still limits

modern computer science with its central

databases and command trees [referring to

recent commentaries]. One example is

'the famous friendship theorem'[we all know

that! The argument apparently is that if

two individuals in a society have one mutual

friend then there must be one individual who

is the friend of all the others. These

two commentators suggest that this leads to an

argument for the philosopher as the universal

friend of humanity, a kind of benign

dictator]. The proposal is to develop

acentred systems instead, with flows being

driven by differences in intensity [this

sounds like a modern conception of embryology

as well, discussed in DeLanda],

forming a graph not a tree, a map in their

terms. Or take collective actions like

the coordination of soldiers in a war machine:

is a general really necessary, or could we

operate with a 'war rhizome', 'guerrilla

logic' (19) [texts advocating this like

Debray's Revolution in the Revolution

were very popular at the time]. We could

model collectives as 'an acentred multiplicity

possessing a finite number of states with

signals to indicate corresponding speeds'[on

the technical notion of speed, see notes on

other chapters], and this might even be able

to resist centralisation. We could

consider anything in this way [or as they put

it 'Under these conditions, N is in fact

always N-1'. Prats], as a calculation,

trying to induce a change in state. We

can even recast psychoanalysis away from its

authoritarian tracings and develop

schizoanalysis, 'the unconscious as an

acentred system, in other words, as a machinic

network of finite automata (a rhizome)'.

The same goes for linguistics. In both

cases, we have to produce the new conception,

and with its new statements, different

desires: the rhizome is precisely this

production of the unconscious' (20).

The tree has been a powerful model of reality

in the west, but then 'The West has a special

relation to the forest'[SIC, 20], and to

deforestation. In the East, the steppe

and the garden, or the desert and the oasis

have produced 'a different figure', the

'cultivation of tubers by fragmentation of the

individual', and a rejection of sedentary

animal raising. [Let's hear it for the

nomads in other words, as in ch 12].

This gets close to claims that the East has

developed something that might be a rhizomatic

model and leads to some fanciful work

explaining all sorts of differences between

western and eastern morality and philosophy,

including a preference for transcendence

rather than immanence, or different images of

god. And music and sexuality ['of the

earth' that is]. In particular, 'the

rhizome... is a liberation of sexuality

not only from reproduction but also from

genitality' [great news for 60s

permissives]. Henry Miller says China is

the weed threatening the orderly cabbage patch

of the West [Oh good. The authors remind

us that this might be an imaginary

China. The politics of actual China was

of course a major issue for French radicals].

What about America? It has been

dominated by trees, such as the interest in

European ancestry, but anything that's

important 'takes the route of the American

rhizome: the beatniks, the underground, bands

and gangs'(21). 'The conception of the

book is different'. There is a

difference between the arborescent East, with

its concern for ancestry, and the 'rhizomatic

West, with its Indians without ancestry [not

after Europeans destroyed their societies

anyway], its ever receding limits, its

shifting and displaced frontiers' [these

blokes have watched too many Westerns].

This reverses the European tensions between

west and east. [And, as a clincher],

'The American singer Patti Smith sings the

Bible of the American dentist: Don't go for

the root, follow the canal'.

Western bureaucracy may also have divided into

different types, whether based on agrarian

societies with trees, more modern societies

like feudalism, inventing property and

developing the state, and expansion through

warfare. 'The Kings of France chose the

lily because it is a plant with deep roots

that clings to slopes'[more totally convincing

argument]. It might be different in the

orient, where the state is not so arborescent,

and bureaucracy works with the hydraulic

model, where the state channels and

distributes classes [apparently based on

Wittfogel on Asiatic modes of

production]. We see metaphors of rivers

to describe rulership. [One obvious

symbol can be easily dismissed by assertion]

'Buddha's tree itself becomes a rhizome'

(22). America as an intermediary state,

both liquidating people [geddit?] and having

flows of immigration and capital, so rootnd

rhizome come together. This means that

'There is no universal capitalism, there is no

capitalism in itself; capitalism is at the

crossroads of all kinds of formations'.

[Dear god! Their stand depends on this

sort of 'evidence'?]

However

'we are on the wrong track with all these

geographical distributions. An

impasse. So much the better'[nothing can

stop them]. The rhizomes also have their

own despotism and hierarchy, and this only

goes to show that there is no dualism either

ontological or axiological, no simple good and

bad, but rather arborescence in rhizomes and

vice versa. Rhizomes can generate their

own peculiar 'despotic formations of immanence

and channelization', and root systems can have

'anarchic deformations'. [After all

this] the two systems are not opposed,

although one is transcendent and the other

immanent. We should also choose either a

model that is forever constructing or

collapsing, or one that prolongs itself.

If we seem to have sneaked in another dualism,

this is because of 'the problem of

writing'. If we want to explain things,

'anexact expressions are utterly

unavoidable'[and are indeed celebrated in

later chapters]. We also tactically use

one dualism to challenge another, moving

through dualist models to 'arrive at a process

that challenges all models'. We have to

constantly correct the dualisms through which

we pass until we arrive that 'the magic

formula we all seek—PLURALISM = MONISM' (23)

[an underlying level of being that explains

all empirical variety—reductive for Badiou].

To summarize, rhizomes connect any point to

any other points, and display traits of

different natures, covering different regimes

of signs 'and even non-signed states'. They

are not reducible to the One or the multiple

[certainly not the one that leads to a binary

series, and certainly not to the falsely

multiple]. It [the rhizome] is composed

of dimensions or 'directions in motion'.

It has no beginning or end, only 'a middle

(milieu) from which it grows and over spills'

[I often wonder if translating milieu as

middle rather than context is helpful

here]. It constructs linear

multiplicities with N dimensions. It has

no subject or object. It moves on a

plane of consistency 'from which the One is

always subtracted (N-1)' [that is,

multiplicities turn into singularities when

they 'cool down', or move to a state with

fewer dimensions, like moving from N

dimensions to three dimensions]. Changes

of this kind are 'changes in nature' as well

[changes in state would be better].

There is no underlying structure with points,

positions and binary and biunivocal

relationships between them. The rhizome

'is an anti genealogy'[that is, it does not

simply involve from earlier to later

states]. It is a short term memory [as

explained above]. It 'operates by

variation, expansion, conquest, capture,

offshoots'. It 'pertains to a map that

must be produced, constructed' with all the

qualities listed above, and the trick is to

locate tracings on the map not the

opposite. The rhizome is acentred and

non hierarchical. It is not a signifying

system. The questions it poses about

sexuality, but also relations with animals,

vegetables, the world, politics, the book, the

difference between the artificial and the

natural, are not answered in the usual

arborescent way, but by positing 'all manner

of "becomings"' (24).

A rhizome is made of plateaus, middles,

borrowing from Bateson to refer to the region

of intensities, developed in Balinese

culture. Plateaus evidently are found

along planes of consistency. Western

thought tends to think in terms of beginnings

and ends instead: 'for example, a book

composed of chapters has culmination and

termination points' instead of a series of

plateaus communicating with each other.

A plateau is 'any multiplicity connected to

other multiplicities by superficial

underground stems in such a way as to form or

extend a rhizome'. 'We are writing this

book as a rhizome', in a circular form 'but

only for laughs'. Each writer decided to

work on a particular plateau.

Hallucinatory experiences helped trace the

lines between the plateaus. Circles of

convergence were constructed, but each plateau

can be read starting anywhere and related to

any other plateau.

Constructing the multiple requires a method,

and 'no typographical cleverness, no lexical

agility, no blending or creation of words, no

syntactical boldness, can substitute for

it'. Indeed, these techniques must be

broken out from their original use which was

to express some hidden unity. Only a few

have managed to do this [and a note refers us

to de la Casiniere Absolument necessaire:

the emergency book, Paris 1973, and also

'research in progress at the Montfaucon

Research Centre']. 'We ourselves were

unable to do it', and used words 'that in turn

function for us as plateaus 'RHIZOMATICS =

SCHIZOANALYSIS= STRATOANALYSIS=

PRAGMATICS=MICROPOLITICS'. We consider

these words to indicate concepts, and, in

turn, lines, 'number systems attached to a

particular dimension of the

multiplicities'(25) including 'strata,

molecular chains, lines of flight or rupture,

circles of convergence etc.'. They are

not offering a science, which is as dubious a

general concept as is ideology [ referring to

the great science/ideology debate in marxism

then raging?] Instead 'all we know are

machinic assemblages of desire and collective

assemblages of enunciation'. We are not

offering significance [SIC - is this a typo?]

or subjectification. We are 'writing to

the nth power' to avoid individuated

enunciation which is trapped by significations

and subjects [so these nasty developments are

wished away by collective writing].

Assemblages act on a number of flows, semiotic

material and social. These effects are

often recapitulated by science or theory, but

at the expense of the division between reality

and representation, and the author [all seen

as 'fields' here]. The assemblage

connects multiplicities from each of these

fields, so books do not just refer to reality

as its object nor to authors as its subject,

nor to other books ['a book has no sequel', a

rather ironic comment in the

circumstances]. They are not trying to

represent some outside, because this would

involve image, signification [again] and

subjectivity. The book as an assemblage

rather than an image of the world, a

'rhizome book'. We should never send

down roots. We should let things occur

to us from the middle not from any

roots. This is not easy, but we should

'try it, you'll see that everything

changes'. This is like Nietzsche arguing

that aphorisms had to be ruminated, hence

'never is a plateau separable from the cows

that populate it, which are also the clouds in

the sky'[I am so pissed off with this poetry].

History is written from a sedentary point of

view, and from the point of view of the state,

even when discussing nomads. We need to

develop instead a nomadology. Rare

examples of this include Schwob's book on the

children's crusades, with multiple narratives

and variable numbers of dimensions.

Another one they like is Andrzeweski's The

Gates of Paradise, which apparently has

a single uninterrupted sentence representing

flows of children and their confessions they

give to the monk, 'a flow of desire and

sexuality' (26). What is important is

the collective assemblage of enunciation, the

machinic assemblage of desire, both plugged

into outside multiplicities. Another

example is Farachi on the fourth crusade, with

unusually spaced sentences, and typography

that begins 'to dance as the crusade grows

more delirious'.

Writing needs a war machine and lines of

flight, but still runs the risk of copying or

modeling or imaging something outside, even

the books above. Maybe the crusades are

only limited examples of nomadism. The

struggle will be to find writing about proper

heterogeneous nomadism. Most 'cultural

books' are but tracings, however, including

tracings of previous books, other books,

established concepts and words. Anti

cultural books on the other hand pursue

'forgetting instead of

remembering...underdevelopment instead of

progress towards development' making

maps. [In this sense, 'RHIZOMATICS=POP

ANALYSIS'- no doubt they had in mind Pop

Art?]. However, these still might

contain 'the blocks of academic culture or

pseudo scientificity' [this book certainly

does]. The best of modern science and

mathematics are nomadic, rather than tracing

concepts. In most cases though, the

state has long been the model for the book

[see chapter 12]. War machines make

'thought itself nomadic', as in Kleist and

Kafka.

So what we should do is 'write to the nth

power, the N-1 power'[via a collective

enunciations and links between different

regimes of signs and so on]. Write with

slogans, such as 'run lines, never plot a

point!'. Develop speed, follow lines of

chance and lines of flight. Don't be a

general. 'Don't have ideas just have an

idea (Godard)'[obscure here, but eventually

explained in the books on cinema]. Make

maps. Be the pink panther'. Take

comfort from the old song about Old Man River

[with a verse reproduced on 27].

The rhizome has no beginning and end. It

is a matter of alliance rather than

filiation. It proceeds by the

conjunction 'and…and…and' [again obscure here

but discussed elsewhere, probably first in Anti Oedipus.

It is really urging us to join together things

that are heterogeneous]. 'Uproot the

verb "to be"'[in other words do not try to

find out what a thing actually is]. Do

not ask useless questions about origins or

destinations. Do not seek foundations or

beginnings - 'all imply a false conception of

voyage and movement'. Follow and admire

Kleist, Lenz and Buchner, who proceed from the

middle. American literature and some

English literature shows this 'rhizomatic

direction' (28), following a 'logic of the

AND'[more of this in Deleuze's work on

literature in the

clinical project]. They practice

pragmatics. We should not see the middle

as the average but something where speed

increases [which I think means something where

we can see the connections between things that

are widely distributed]. The notion of

between should be seen as 'a perpendicular

direction, a transversal movement that sweeps

one and the other away', just as we can see a

stream without beginning or end picking up

speed and undermining its banks.

back to menu

page

|