|

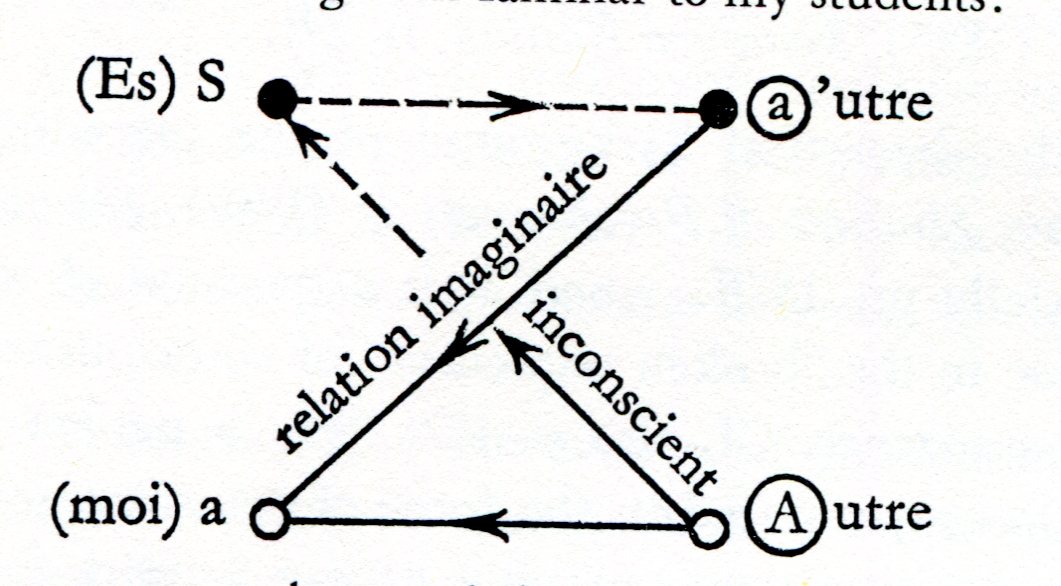

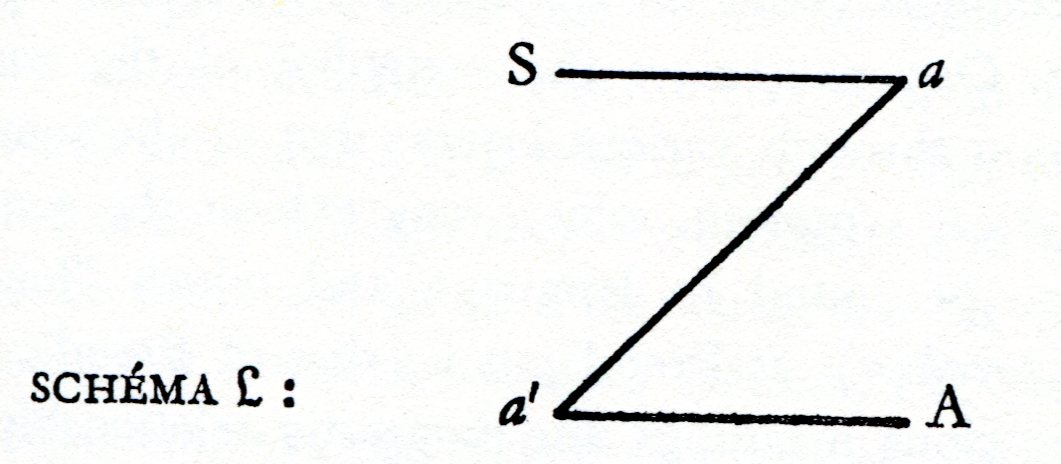

Dave Harris Translators Introduction The style is described as 'dense and allusive' and it is not clear whether he 'the spelling out the obvious or contributing to the ambiguity of the ambiguous' (vii). Summary is impossible, so is any attempt to reduce the style: Lacan himself has said that we have to be very vigilant in the use of 'the Word'. There are 'few concessions to the uninitiated' (viii), and 'the characteristic French carelessness over references, usually relying on his audience to recognize the echoes from his own and other works', which gives problems if you are not located in that context or tradition. It presupposes deep acquaintance with Freud and with Heidegger and Sartre,, with a corresponding 'technical and philosophical vocabulary' as well as with structural linguistics and structural anthropology. There is also the French tradition of precociousness. It should be read as offering 'brilliant and provoking intuitions, couched in aphoristic form' (ix).. The notes refer to some earlier works from the same period and some technical terms explained. There is also an essay. [An intellectual biography ensues. Apparently, Lacan discovered the importance of language from his earlier phenomenological attempts to describe psychoanalytic experience. He became aware of the important implicit relation with the other in language, and how the analyst should be seen as an important listener or interlocutor. Later transference will be explicitly described as a dialectical relationship between subject and subject, with language offering a clear objectification of the properties of the patient, partly revealing the analyst's own prejudices or passions. This notion of transference, especially counter transference, is linguistic in origin, appearing in permanent forms of communication which constitute objects. It affects both subjects in the analysis. It offers a series of blocks to further analysis and must be overcome by a definite technical neutrality, trying to grasp how patients project their own past into a discourse, and how the analyst is also the intended listener, someone who will help with meaning. Lacan wanted to initially promote the Imaginary order '(perception, hallucination, and their derivatives)' (xii), the Symbolic order '(the order of discursive and symbolic action)' and the Real. These were initially found in the mirror stage as the root of all subsequent forms of identification. The symbolic order is to be understood through anthropology, 'especially by Marcel Mauss and Lévi-Strauss' (xiii). The mirror stage is the centre of 'Lacan's heresy', although Lacan claims that it is based on a return to Freud: he was responsible for reintroducing him in French, and in staving off existential readings which were then popular. He also integrated Lévi-Strauss with psychoanalysis and used the terms of structural linguistics especially metaphor and metonym, the signifier and the signified. He distinguished between 'need, demand, and desire'. His seminars have been substantial events, attended by the Tel Quel group including Roland Barthes, Foucault, Derrida and Althusser and students from a number of disciplines. His revived interest in Freud. This piece was originally published as a discourse in a journal, La Psychoanalyse, and republished in Ecrits. Méconnaissance is translated as '"failure to recognize"'. Capital letters indicate special usages. Phantasy is a standard Freudian term. [According to the Klein Trust it means 'the mental representation of those somatic events in the body that comprise the instincts, and are physical sensations interpreted as relationships with objects that cause those sensations. Phantasy is the mental expression of both libidinal and aggressive impulses and also of defence mechanisms against those impulses. Much of the therapeutic activity of psychoanalysis can be described as an attempt to convert unconscious phantasy into conscious thought...{Freud} thought of it as a phylogenetically inherited capacity of the human mind. Klein... and her successors have emphasised that phantasies interact reciprocally with experience to form the developing intellectual and emotional characteristics of the individual; phantasies are considered to be a basic capacity underlying and shaping thought, dream, symptoms and patterns of defence.] 'Meaning' or 'sense' implies subjective meaning, while 'signification' implies objective [it is the same word in French sens] . Discourse can sometimes mean a more general form of human communication as when kinship systems communicate about marriage. The French terms do carry extra meaning, just as the German ones do in Freud although the distinctions are not always carried over into translation. [My own intentions are much less exalted, of course -- to gain a basic understanding of some of it, especially re the debate with Deleuze and Guattari] Prefatory Note The context for this piece was an early split between different psychoanalytic movements in France. A particular turn criticised by Lacan tried to argue that everything human could be understood by a single discipline — neurobiology. Lacan offers many criticisms. Lacan launched further splits. In one of his pieces for La Psychoanalyse, he defines discourse as 'a process of language which compels and constrains truth' while analytic discourse involves '"the putting into place of unities which produce and repeat themselves, whatever may be the principal it assigns to the transformations of working system. Analysis, then, properly so-called, is the theory which treats of concepts of elements and combination as such"' (xxiv). There are also implications for the training of analysts and how to deal with transference and counter transference, but there have always been general concerns about 'the status of human discourse in analysis'(xxv), as opposed to behaviourism or biological accounts of instincts, or a medical approach towards symptoms. Stressing discourse puts 'the status of the subject in question', which Freud did. Lacan's presentation of this piece divided the audience. Some wish to prevent him from speaking. Lacan was to argue that there were no clear theoretical principles and psychoanalysis at the time, not relying on Freud was a better way forward even though they were ambiguous. He proposed to clarify them by linking to language as understood by structural anthropology. At least, they had to be kept from being submerged in 'routine usage'. Psychoanalysts have to be discouraged from seeing their own work as something magical. Schools of psychoanalysis should not tightly regulate membership. Psychoanalysts should be much more reflexive about their own activities. Nevertheless, this piece was written in haste, but that also shows that the Word is central to creation, in this case helping to explain the disorder of psychoanalysis, '"in order to comprehend [its] coherence in the Real"' (xxviii). Modern psychoanalysis has lost interest in the role of language in favour of an emphasis on the resistance of the object — for Lacan 'an alibi of the subject'. In particular, psychoanalysis has failed to grasp the function of the Imaginary or fantasies and how objects of been variously constituted at different stages [note 2, page 92 explains that people experience the Real through the imaginary and the symbolic functions. The Imaginary that lacks sufficient power of distinction, and thus '"inundate singularity", and so cannot be grasped rationally and has no "dialectical movement". However, symbols have an Imaginary support. In dreams, the symbolic becomes imaginary]. Current efforts to explain the imaginary seem to wrongly locate it in the infantile preverbal stage. The second problem turns on the libidinal implications of objects [which again ignores the symbolic. Note 3 on page 93 says that phenomenological or existentialist analysis is particularly being rebuked here to the extent that it ignores language — and see the piece on the mirror stage]. The third problem concerns counter transference and what the analyst does. The analyst cannot be separated from the analysis, but their obvious effects have been sought in the unconscious of the patient. We must look instead at apparently ineffable stages where the word emerges, say in childhood training. Analysts should also stick to their own language rather than use one which 'offer[s] compensations for ignorance' (4). This is the proper focus for psychonalysts — 'the study of the functions of the Word' (5). Freud himself demonstrates the importance of language, say when he investigates children like little Hans by discussions with his parents, or when looking at Schreber's text, although he claimed his own was a master discourse. Modern psychoanalysis has become a matter of formal technique, rather similar to obsessional neurosis, a 'closed circuit' between inadequate initial definitions and ensuing problems. Psychoanalysis might be used on modern psychoanalysts [note 9 explains that it is no good to just tell the patient the meaning of his symptom — the point is to encourage recognition and to overcome initial misrecognition]. Instead, criticisms seen as aggression, and technical issues seem to be decided by voting. Instead, there are Symbolic, Imaginary, and Real conditions producing defence mechanisms turning on our desire not to be isolated or undo what has been done, classic obsessions and classic forms of 'denegation' [Verneinug]. These features are apparent especially in the American group. At the Symbolic level, the characteristic historical dimension of communication in the USA is an opposite to psychoanalytic experience [? Their emphasis on clear simple communication?]. Behaviourism dominates their psychology. Analysis at the other two levels might also be possible, focusing may be on the imminence of particular individuals and their enterprises: Lacan suggests this may be something to do with the domination of immigrants to the USA, and the 'distancing' consequences on American culture. There is an emphasis on the adaptation of the individual to the social environment, to wards trying to establish acceptable patterns of conduct, often seen as objectified human relations and involving human engineering. Yet this is a study of the individual that ignores the unconscious and sexuality. The consequences been to ignore the role of language and with the specialist language of Freud. Underlying motives for conduct are not sufficiently explored. A return to classic approaches is required to combat this new orthodoxy. The first task is to properly grasp the underlying concepts, and to do this, we must examine 'the domain of Language… The function of the Word' (8). This will require close reading Freud to avoid seeing his concepts as mere 'homonyms of current notions', seeing his work on the mythical content of instinct as a literal theory, for example. The specific case [identified in note 19 page 97] shows how it's possible to draw logical conclusions from 'an original misunderstanding'. Section 1 Psychoanalysis can only work with the patient's Word as intermediary. And there is no word without a reply, even if it is silence. Not realising this exposes us to the power of the Word all the more, although this is often experienced as a need to seek some external reality. Thus some people analyse the behaviour of the patient in order to find what the subject is not saying, although talk is still necessary — however it is still seen as a substitute for failure to analyse. We should recast all this as trying to establish some ultimate truth, expressed in talk about 'humbler needs' (9). Underneath that is an 'appeal of the void' found in all attempted seductions of the other. It is not a matter of introspection. That really delivers anything of value, although [particularly narcissistic] patients like introspection, but can sometimes experience the results as ridiculous. Monologues offer a 'mirage' (10). A particularly forced version of introspection can be found in the practice of free association. That is real labour, but practice produces only 'a skilled craftsman' rather than an analyst. Processes of '"working through"' are likely to encounter 'the triad: frustration, aggressivity, regression'. Intuition risks delivering only the self evident. In the practice lurks a dubious notion of affectivity — the very 'stigmata of our obtuseness regarding the subject' (11), and as dubious as 'intellectualisation' instead of real understanding. What produces frustration in the patient? Silence is not as bad as mere approval of 'the subject's empty Word'. The very discourse of the subject often involves going back on words, and the subject becomes aware of the alienating disconnection of his being, following mere tinkering with his words. [Note 27 explains that Lacan thought it necessary to distinguish the person in analysis from the person who is speaking. The listening analyst is the third person. The 'me' as opposed to the I makes a fourth person. All this is necessary to understand neurosis. Somewhere in here is a reference to discourse about the self producing an image in the Imaginary]. All this explains that frustration is central to the ego who will always experience alienated desire: this alienation gets worse if the patient is allowed to just elaborate his discourse. Any attempts to reassert some authenticity by recalling the patient's initial image of himself are likely to be frustrated by the approval and pleasure of the analyst. Generally, no reply to the subject's discourse can never be adequate. The aggressivity of the patient is not just to do with frustrated desire, which most people can regulate, but it is rather 'the aggressivity of the slave' who can only respond to frustration with 'desire of death' (12). The analysts intervention is often seen as an attempt to dismantle the imaginary object being constructed by the subject. The resulting aggression is sometimes seen in terms of 'resistance'. [Somebody specific is rebuked here]. Instead, we have to see that the intention of the subject to produce an image cannot be detached from symbolic relations which express it. We cannot distinguish between the speaking 'I' and the 'me'in the patient self. The analyst must see gestures as 'silent notes' to accompany and narcissistic discourse [rather than as privileged clues to inner states as in Freudian slips?]. There must be no collusion in the objectification and alienation of the subject. The certainties of the subject should be suspended and left to play out in a full discourse [note 31, page 101, says the analyst can then point out the vein and therefore regressive character of these certainties, at the expense of anxiety]. The patient's discourse should not be seen as completely empty, however, but rather as a token or password leading to further understanding via connections. The discourse is a form of communication, further confirmation that 'the Word constitutes the Truth' (13), even if the intention is to deceive. Analysts are able to respond to different parts of speech, seeing the 'recital of an everyday event for an apologue addressed to him that hath ears to hear', for example. Even pauses and silences can confirm meaning. Adjournments of the session should also positively punctuate the discourse. The point is to encourage regression, 'the actualization in the discourse of the phantasy relations reconstituted by an ego' (14). There is no real regression. It is a matter of inflection or turns of phrase in language, sometimes that has to revert to baby talk. Seeing regression as a state of present reality is another form of alienating illusion, or 'an alibi of the psychoanalyst'. This is an example of how misleading it is to think of attempting to contact the subject's own reality as in intuitive or phenomenological psychology. The relation between analyst and patient 'excludes all real contact'. Analysts [the one who claimed to be able to contact the real?] really offer a kind of 'second sight', as instructive for them as for the patient. What is really happening is that the patient filters his own discourse, often in the form of 'a ready-made stereoscopic picture' (15) which the supervisor can read as made up of several themes [three-dimensional, like the real?], rather like a musical score. Perhaps swapping roles would make this clear [note 35, page 102 points out that the role of language would be clear if there were a third analyst involved]. Recommendations for a suitable form of attention to the subject should stress that focus should be on the word not on some object beyond it. Focus on objects would surely involve some other mode of analysis. The object really involves the Imaginary relation where the patient appears as a 'me'. This should be dealt with by selective attention: there is no other way to approach the unconscious [note 36, page 102, cites Freud on the need for tuning the unconscious of the analyst in order to pick up what the unconscious of the patient is saying in free association]. So far we have been talking of 'the empty Word' where the patient is not talking about his own desires. In those cases, the recapture of memory is a crucial part of the therapy, intersubjectivity is the focus, and symbolic interpretation replaces the analysis of resistance. Here we see the full importance of the Word. We know that Freud's method was called the talking cure by one of Breuer's patients. That patient, an hysteric, [Anna O] led to their discovery of the traumatic experience as a cause of the symptom. Putting the event into words led the symptom to disappear, as long as recollection was vivid enough [note 37, page 103, explains that it is the putting of the experience into words which is crucial, that speech offers a way out]. The patient becoming aware through speech is still much more important than mere accurate recollection. Freud was also aware that speech under hypnosis was not a matter of becoming aware. The same confusion between becoming aware and mere verbalization also limits behaviorist applications. Becoming aware enables the connection to be made between the present time and the origins of the events, and communicates it to others. Just as with Greek speech [!], The speech of the patient here is indirect, placed in quotation marks, implying the presence of others. [Lots more classical allusions ensue to distinguish this sort of therapeutic memory or re-memory and the mere recollections derived under hypnosis]. Becoming aware is located both in the Imaginary and the Real. The point is not whether it is true or false exactly, but rather that it offers a notion of 'Truth in the Word'(17). Its truth lies in its relation to contemporary reality. Only the Word can act as a witness to past events however. The Freudian test of continuity in recollection is not that each authentic incident should recall the entirety of the past [apparently implied by Bergson], but rather a matter of arriving at the history which balances 'chronological certitude' with an account of the primal scene, but he wants to explain 'all the resubjectifications of the event' (18) in order to explain its effects, re-structuration is that take place after the event. The patient had periods where the primal scene was latent, but Freud ignores those [note 46, page 105 says Freud explained this in terms of deferred action], even though, these periods indicate 'times for understanding'. At particular moments, the patient was able to decide what the original event meant. Lacan sees these differences between times for understanding and times the concluding as functions linked purely logically [note 47, page 105, relates an experiment where three prisoners have to discover who is wearing a black or a white patch on the back. They cannot communicate directly. They only solve the problem by putting themselves in the place of the others and trying to work out deductions by looking at actions in time. First they wait in time for understanding — no one moves, so no one can see to black patches — followed by a time for conclusion where each concludes that therefore he has a white patch]. The whole novelty of the Freudian approach turns on the way in which the patient reconstructs his history in language addressed to the other. This account still might show particular discontinuities, and other methods may be equally good at treatment, but only the Freudian method explains the symptom rather than just hoping to cure it. The result of these admittedly limited approaches was nevertheless 'to constitute a domain' (19). The use of the Word is central to convey a meaning; the domain is the concrete discourse; it operates in history that is one which 'constitutes the emergence of Truth in the Real'. When people commit to analysis, they accept that they will be doing it in locution. This in turn implies a listener or co-locuter. So 'the locuter is constituted in... intersubjectivity' (20). Speech and response is the only way to show the continuity in the subject motivations: this can only appear in 'the intersubjective continuity of the discourse in which the subject's history is constituted'. The subject may vary his account of his history, for example under the influence of therapeutic drugs, but only 'psychoanalytic interlocution'will be effective. The Freudian unconscious can be understood as a part of that discourse, something 'transindividual', not immediately available to the patient in his attempt to reconstruct a continuous discourse [although note 50 explains that insights disclosed during psychoanalysis, or rather transference, are particularly convincing to the patient]. At this point, note 49, pages 107-8 clarifies Lacan's elaboration of the notion of intersubjectivity. It is not just the relation to the other. The subject has to emerge from signifiers which '"cover him in an Other"', and only then can he emerge as a subject with desire. The emphasis on the thinking cogito confuses the subject and consciousness in general, which will be based on misrecognition and the influence of the mirror stage. Human beings are caught in the Symbolic order from the beginning. Subjectivity appears to emerge from consciousness because of the incompleteness {béance, apparently implying openness and vulnerability} of the Imaginary relations toward others. Only the Word permits a full entrance into subjectivity, as we see with the fort! da! game. This moment is constantly reproduced whenever subjects address themselves to the Other. This Other is absolute, and can nullify the subject by making him into an object. This is the '"dialectic of intersubjectivity"' which runs throughout Lacan's analysis. It is represented in the famous diagram Schema L {lambda} ['inconcsient' is the unconscious. The terms are not translated because Lacan apparently insists they are not ordinary words but scientific terms]. The imaginary relation is what goes on in the mirror stage as a form of reciprocal objectification:  A more simplified diagram also appears, happily with some comments.  Returning to the main text, the unconscious relates to a part of a discourse that is not trans-individual nor at the disposition of the subject in constructing his own history. It is not just a matter of unconscious tendencies, because experience shows that the unconscious also participates in the formation of ideas and of thought, as in the discussion of what constituted unconscious thought in Freud [apparently in the Wolf Man]. There is a therapeutic implication in the slogan that there is forgiveness in the word [in Latin in the original]. Communication between the unconscious and the unconscious is often hidden, which makes the subject appear to be offering a personal history and truth. This relation is not grasped by any attempt to formally distinguish conscious and unconscious, but rather by experimental observation. The unconscious is commonly censored or appearing as a false recollection, but the truth can be found somewhere else. First in 'monuments', like the body in hysteria; in 'archival documents' like childhood memories which have to be grasped like any historical document; in 'semantic evolution', the ways in which people develop the particular vocabulary as they live their life; in 'traditions' including legends used to account for history; in those traces produced by distortions linking censored sections to other episodes, to be recognized by 'my exegesis'. (21) these are all metaphors used in Freud himself, where the metaphor 'is but the synonym for the symbolic displacement brought into play in the symptom' [leading to a whole understanding of Freudian mechanisms like condensation and displacement as metaphor and metonym respectively. Freud himself is quoted in note 53, page 109, referring to '"words and names"', passwords, or words that switch affect between different representations in the unconscious, and sometimes between those and the body]. [A certain Mr Fenichel is rebuked for discussing the patient's history in objective rather than subjective terms, related to the 'laws of history' in general. Lacan thinks these efforts, including those of Comte and Marx are hopeless predictors, at least without constant amendment.] They are good as ideals, however. Psychoanalysis and other 'sciences of the particular' might need to locate these facts in 'a primary historization' (23). It is also the case that historical events need to be interpreted and have different effects on the memory, and some remain in the memory longer and continue to play an important role in the present — e.g. past revolutions for Marxists. The patient is taught to reconstruct his history in the present, but by acknowledging that past events can be seen as 'facts of history' (23) for him, either recognized or censored. Any fixation can be seen as 'a historical scar: a page of shame… or a page of glory'. The discussion can be brought to bear in debates about the role of instincts or drives. 'The instinctual stages, are already organized in subjectivity' (24), as when children regard as defeats and victories matters such as potty training. Psychoanalysts use the same kind of subjectivity to reconstruct things like the pre-genital form of love [an important point against Ettinger?] The alleged biological stages are founded in intersubjectivity, not in terms of a maturing of the instincts. It is a mistake to link human development to that of animals like this. Sarcastically: 'why not consequently look for the image of the moi in the shrimp, under the pretext that both acquire a new carapace after shedding the old?' (24). [Another theorist is also sarcastically criticized for claiming to have found a biological plan to explain human culture — the development of armour links to the development of crustacea]. There is a problem with these analogies. They're not as precise as metaphors, and Freud avoided them. Analytic symbolism is opposed to analogical thinking. [More problems with instinct theory are explored page 25, complete with Freud's own objections, again in the Wolf Man, page 26]. The cure, a form of grace, is the 'fruit of an intersubjective accord imposing its harmony on the torn and riven nature which supports it' (26). The subject is a lot more than what is experienced subjectively. The truth of our history is not entirely contained in our script: we have to investigate the signs of disorder and discomfort in that history. In particular, 'the unconscious is the discourse of the other' (27) [note 59, 110 notes that this increasingly becomes the big O Other]. We see this in the occasional convergence between the patients remarks and those of the analyst, or sometimes another patient. This is not telepathy but 'resonance in the communicating networks of discourse'. Human discourse is omnipresent, and is the only field where experience provides an apparent two-way relation, although that is inadequate for psychoanalytic theory [as the diagrams indicate]. Section 2 Symbol and Language We have to avoid any analysis that relies on homonyms between analytic terms and everyday ones. Conventional psychology tends not to grasp the highs and lows of common experience. Psychoanalysis also typically ignores these aesthetic sensitivities or impulses, 'the vivacity of his tastes' (29). We should investigate the positive aspects of experience, but not as is commonly done in conventional psychiatry [which seems based on some idea that pleasures and desires lie beyond language in object relations]. We want to develop a more scientific approach by returning to the work of Freud. In the work on dreams, the dream 'has the structure of a sentence', in particular, that of 'a rebus'[The Oxford Dictionaries Online give 'A puzzle in which words are represented by combinations of pictures and individual letters; for instance, apex might be represented by a picture of an ape followed by a letter X']. Thanks to the 'laws of the signifier' [as note 65, page 111, puts it], the elements can provide both a phonetic and symbolic use as with Egyptian hieroglyphs or Chinese characters. Further interpretation and deciphering is required, however, a 'translation of the text', the 'rhetoric' of the dream. Here we will find forms of 'syntactical displacement' – ellipsis and pleonasm, hyperbaton or syllepsis, regression, repetition, apposition' [haven't bothered to look them all up] , and 'semantic condensations' — 'metaphor, catachresis, antonomasis, allegory, metonymy and synecdoche' (31) [these are explained in formal linguistic terms in note 67, page 113. Metonymy connects words to words in a signifying chain, signifiers to signifiers, and this 'represents the subject's desire'. Metaphor substitutes one word for another and here the first signifier becomes a signified, still connected by metonymy. Lacan apparently represents this in another diagram. He connects it to Freud's work on the dream specifically. For example transposition or distortion is understood as 'the sliding of the signified under the signifier, always in [unconscious] action' [possibly as intentions and motivations develop or reactions occur?]. Condensation involves the superimposition of signifiers and is central to a general poetic function. Displacement is the transfer of significations and is used 'by the unconscious to foil the censorship'. The mechanisms in language and in dream work are identical, except for their dramatic staging {mise en scene} . Lacan was to argue later that this connection between signifiers permitting elision, is what invests an object with desire which it originally lacks. It does this through a process of referring back]. Freud argued that the dream expresses desire, even where the patient dreams specifically in a way to contradict his theory. This episode shows us precisely how the wishes of the other are generated by the first speaker, and Freud also noticed the role of the desire to contradict. Freud was to realise that the sign of transference was the appearance of provocation, avowal or diversion from the analytic discourse. We can generalize from this to insist that 'man's desire finds its meaning in the desire of the other… the first object of desire is to be recognized by the other [note 68, page 114, tells us that Lacan gets this idea from Hegel, that desire has always to be mediated, increasingly in a dialectic. Lacan elaborated his ideas later to argue that desire is an effect of a discourse, that it operates via signifiers. Since the Other is where the Word is deployed, '"man's desire is desire of the Other"'. The whole thing depends on the opening/vulnerability {béance} of signifiers which permit the structure of the subject's desire and the representation of the Other. Human subjects are commonly unaware of the role of the Other in structuring their desires, however]. This is best demonstrated in transference. The patient's dream becomes a matter of 'provocation... avowal... or diversion' according to the analytic discourse and, as transference proceeds, dreams become more and more related to this dialogue. Similarly, a parapraxis is 'a successful discourse', a particular phrase, affected by a stifling of speech. Again we see the power of the Word which will convey a meaning other than the literal. Freud also examines beliefs about chance, found in subjective number associations, for example. Numbers arrived at through particular manipulations should be seen as symptoms, 'already latent in the choice from which they began'. Superstitious people think that these figures determine their destiny, but this is an effect of the particular language expressed in these combinations of numbers, appearing as unconscious to the subject. There are other unconscious structures revealed by philology and ethnography [the latter meaning Lévi-Strauss?] A symptom is always overdetermined by a double meaning, one relating to the past conflict and one to a present one. Free association is a technique to locate the point at which verbal forms intersect with this underlying structure. The whole thing can be understood as an analysis of language. [Again, note 70, page 115 tells us, it is understanding the ambiguity of language as an orchestral score. The connection between the symptom and the underlying structure is like the link between a rebus and a sentence. This ambiguity is not the same as overdetermination of symptoms, except that both refer to relations of signifier and signified. The symptom is always a signifier, unlike medical symptoms: it is not just an indicator, but an effect of language, here understood as actual spoken daily language. Signifiers and signifieds are related 'as system to system', not just as simple terms, so symptoms display a whole structure of significations, not just an isolated one]. Freud demonstrates the effect of the unconscious in his work on jokes where a particular phrase or word is the turning point of the joke, making the meaning 'sufficient to the wise' (32). The whole effect depends on the ambiguity engendered by language, and where nonsense is allowed to challenge the usual view that consciousness dominates the real. Human speakers lose mastery. It is not that the joke somehow engenders its own logic, or that sophistry controls humour. Instead we discover a certain conditionality of subjectivity. If there were nothing foreign to my consciousness, they would be no pleasure in discovering it. There is always an implicit third listener, sometimes indicated by making the joke turn on indirect speech. The truth by contrast looks like a platitude. Turning away from the language of symbols is actually a change in the object of psychoanalysis – activities like jokes constantly remind us of the creative power of language. The law is also a law of language. Ancient Greek travellers initiated 'symbolic commerce' which eventually turned into an exchange of signs. The gift already implies a pact, and we rapidly developed purely symbolic exchanges like goods that were not actually very useful. This activity might be seen in giftgiving among animals like sea swallows, and if their gifts really are the equivalent of a human celebration, they are indeed using symbols. So the origins of symbolic behaviour might indeed lie 'outside the human sphere' (35). But we must not over elaborate the sign. In one example, a behavioural psychologist has managed to reproduce what looks like neurosis in a dog by varying the rewards that arrive with the bell. This is supposed to show the links between signals and symbols. It is certainly true that you can condition animals and humans with signals. However, humans can react ambiguously to signals [the exact example implies the use of a command word like 'contract', directed at eye pupils; the same word in other contexts would not produce pupil contraction]. This involves distinguishing the signifier and the signified, and this in turn implies that words makes sense only by being part of a given set, pre-existing any individual experience. Freud centrally maintained the importance of relations to the Symbolic order and the sense that results. With trained animals, there is always the danger of 'an irrelevant humanism' (38) which misunderstands the intersection of conditioning with the deployment of words. Animals cannot reproduce the social world, completing a symbol. Symbols need to be liberated from specific uses in the here and now, and this is possible only if it behaves like a concept. Freud saw this in the Fort Da game, where an absence can give itself a name, and when it is only the relation between the terms that constructs particular 'universe of sense in which the universe of things will come into line' (39). In this way, 'the concept… Engenders the thing'. The world of words creates the world of things which appear in the here and now as confused, still connected with the becoming of the whole, localised. The exchange of gifts including the exchange of women and the reciprocity implied shows how the symbol 'has made… Man'. Things like kinship names help construct a preferential order. This remains unconscious, but there is a whole underlying 'logic of combinations' (40) [Lévi-Strauss]. As usual, we only think we are free in these matters because their permanence lies in our unconscious. The same might be said of the Oedipus complex, which involves unconscious participation in the movement of marriage ties, but we become aware of it only through symbolic effects in our individual existence, in this case in the form of a 'tangential movement towards incest'. The 'primordial Law' [of incest prohibition] is necessary because our nature offers unrestricted copulation requiring cultural regulation. The conscious warnings about incest are only a 'subjective pivot' and can help to explain 'the modern tendency' to focus restrictions on mothers and sisters. Overall, the law prohibiting incest 'is revealed clearly enough as identical to an order of Language', for example in requiring kinship nominations. Breaking the law would produce unendurable confusion of roles. Even remarriage with a young woman of the same age as one of the sons can produce problems 'as we know was the case of Freud himself' (41). There is a further 'dissociation' of Oedipus when people believe that they are reincarnating ancestors. The paternal function when represented by a single person therefore 'concentrates in itself both Imaginary and Real relations, always more or less inadequate to the Symbolic relation which constitutes it essentially'. Hence the 'name of the father' is an eternal support of the Symbolic, identifying the person of the father with the figure of the law. When we analyze cases, we have to remember this function and distinguish it from the Real relations: harmful confusion results if we do not do so. [Referring to Rabelais], we see the same [paternal] relations in the notion of an omnipresent spirit, a divine mystery. This brings with it an 'inviolable Debt' (42) which guarantees the continued circulation of women and goods [possibly some sort of common value? Note 97 cites a certain Panurge as seeing debt as the mainstay of the human race, '"the great Soul of the universe"', presumably because it is crucial in exchange and social obligation? 127] Lévi-Strauss was to refer to this underlying notion as the symbol zero, making the power of speech a matter of an algebraic sign. [Note 98, page 127, explains that for Lévi-Strauss the spirit was an overabundant signifier, with a kind of surplus signifying value permitting symbolic thought. This surplus value, the floating signifier, is represented by mana or spirit, which may take any number of specific forms. Mauss was to argue that its real function was in symbolic exchange, that mana was being exchanged regardless of economic advantage. Lévi-Strauss wanted to see it as a symbolic zero partly as a nod towards Jakobson and the notion of the zero phoneme which exists as a standing opposition, to replace the simple absence of phonemes. For Lévi-Strauss, mana is 'pure form without specific content, pure symbol, a symbol with the value of zero'] The interlocking network of symbols exist before any individual. It seems to provide people with meaning, with a destiny. However, universal meaning is subject to local variations arising from both 'interferences and pulsations' within language, a 'confusion of tongues' and sometimes a contradiction of perceived orders. These preserve the role of desire, but desire must therefore be recognized in symbols or at least in the Imaginary. In the case of individual patients, this takes the form of a pathological intersubjective experience. It follows that everything turns on 'the relationships of the Word and Language in the subject' (42). As a first paradox, among the mad, we can see both the freedom given to words which no longer need to be recognized, and a delusion which objectifies the subject in a 'language without dialectic' (43) [note 102, page 129, says that Lacan initially saw this in terms of a general structure of meconnaissance/misrecognition. He insisted from the beginning that a form of misrecognition is common in everyday life as well, as when people take themselves seriously. A language without dialectic is found in schizophrenic language: words are treated like things, so the binary differences between them are not anchored in the symbolic end – 'all the Symbolic is Real' (130), so there is no dialectic or dialogue, since words have no shared meaning. This 'deficiency of signifiers' means there can be no real contact with the (Symbolic) Other, but only with the (Imaginary) other. Since human reality is symbolic, schizophrenics and psychotics find it hard to locate themselves in the 'human Real'.] The language of the psychotic is stereotyped, symbols are petrified, appearing rather as do myths for us. They are not recognized in the usual way. It might be possible to see such people occupying particular places in society? In the second paradox, psychoanalysis has discovered particular elements such as symptoms, inhibition and anxiety. Again the Word is not available for concrete discourse by the patient. Instead discourse is the result of organic stimulus, or perhaps marginal images from the social world: at best it relates the inner world of the person to the outer subjective world. Some signified was once related to a signifier but this has been repressed from consciousness, and can only appear through 'semantic ambiguity'[note 107, page 131, explains some of the cultural allusions to Roman religion and goes on to say that the apparent 'lack of being' in psychotics is, in Sartre, the basis of desire for the self — it seems to be that personal liberty is possible only once we have escaped necessity, that this personal liberty belongs to our desire for selfhood, but that what is lacking is this 'desire of being', possibly meaning a way of reconciling possible liberty with social reality?]. The banishment of the Word also banishes 'the discourse of the other' which is included in it from the beginning. Understanding these original meanings led to Freud grasping the importance of basic symbols which still have a role in current civilization. All the symptoms of neurosis and psychosis can be seen as 'hermetic elements' (44), equivocations, artifices, containing sense in prison, in a palimpsest. Restoring the Word and its suppressed elements offers both a mystery and a 'pardon'. In the third paradox, subjects can lose themselves in objectified discourses as a kind of 'profound alienation of the subject', very common in scientific civilization. [Typically obscurely] common speech once referred to 'that which I am' and now refers to 'it is me'. This 'psychological objectification' is characteristic of modern man [and may be paradoxical in that modernization involves disorder of the old harmonies? Or possibly that the desire for fellow feeling, the beautiful soul, is contradicted by an interest in individualism?]. A delusional discourse offers a way out. We now have a form of communication based on objectification which allows people to forget the paradoxes of subjectivity and enables them to still contribute to the common good and find pleasure and forgetting in the profusion of cultural materials. It is only when regression reminds subjects of their limits, perhaps back at the mirror stage, that this capacity is questioned. Psychoanalytic discourse itself breaks the illusion by referring to a trinity of ego, superego and id. Patients commonly display a barrier in their language resisting the Word and preferring instead the sort of 'verbalism' (45) found in normal life. We see this also in the tremendous output of modern culture and we might study questions of language in that output. Psychoanalysis, by insisting on the truth of the Word, threatens further alienation [Lacan defends himself, says note 116, page136 by implying through Pascal that it is sometimes necessary to be mad if civilization is itself, that there is a connection between madness and sense, and that madness results only when the normal forms of understanding one's personality as dependent on others breaks down. Thus madness has both a human and the philosophical value, telling us about "signification for being in general". Madness arises from a permanent paradox of managing self and other, and is a companion to liberty, perhaps a limit of liberty]. However, subjectivity does play an important role both in renewing symbols and it 'continues to animate the whole movement of humanity' (46). At the same time, it only works as something symbolic. Even revolution gets 'reduced to the words which signify it', while established religion finds its power increasingly in Language. Psychoanalysis has also done much to develop notions of subjectivity, although it must not be grounded as a discipline among the sciences, formalised, in some misleading attempt to catch up, to develop misleading experimental methods. Instead, the Symbolic function needs further investigation [possibly hinting that the progress made by structural anthropology might be a model]. The need is to reverse positivism with its emphasis on the experiment, to go back to an earlier model. The developments in linguistics and its links with anthropology can guide us. The discovery of the the phoneme is the basic unit formed by oppositions of semantic elements can even take on a mathematicized form. All languages can then be seen as combinations of small numbers of phonemic opposition. Psychoanalysts need to explore the implications just as ethnography has in the study of myths and mythemes in Lévi-Strauss [with an interesting note 120 on page 137, which tells us that Lacan explicitly grasped the Oedipus complex as a myth]. Lévi-Strauss is cited as one of the 1st to combine the structures of language with social laws on marriage and kinship. Investigating the symbol will provide a new science of man and subjectivity. The Symbolic has a double movement [rather like Berger and Luckmann here, as well as Hegel]. Human beings objectify their actions but that objectification becomes a grounding — 'action and knowledge alternate' (48). As one example, education shows us how to objectify in cardinal numbers things that have been counted, but once we have these numbers we can see that they can be added; in another example human beings see themselves as producing social relations, but can also threaten those social relations in the name of some deeper belonging [the example is the proletariat going on a general strike]. Both instances involve regularities — mathematical laws and 'the brazen face of capitalist exploitation'. Both show us how our social life takes on a reality, as inversions and reversals dominate the concrete, and how subjective investigations can grasp reality. The old distinction between exact and conjectural sciences is undermined. The apparent exactitude of experimental science really comes from mathematics, while its relation to actual nature remains problematic. [With an irritating citation of a poem producing speculation that the unusual link between humans and nature might actually tell us about the movements of nature itself], whereas physics 'is simply a mental fabrication whose instrument is a mathematical symbol' (49): it measures the real but does not really define quantity in real substances. We see this in the measurement of time which still depends on particular assumptions [an historical example argues that an efficient clock was developed before theoretical work that would supply a concept]. There is another kind of time which is intersubjective and which structures human action [not Bergson and durée though] but a stochastic notion best understood through game theory strategy. Human time is rooted in action oriented to the actions of others with all the hesitations, certitudes and final decisions, and the eventual notion of past and future which are implied. The other is crucial here in confirming the understanding or final decision of the subject as a matter of truth or error. Boolean algebra or set theory might do a better job of grasping the structures. Historians suggest another route, where they identify their own subjectivity with that which constitutes historical events. Psychoanalysis is similar, with added notions of 'curative efficacy' (50). We also realize the effects of historicity which enables us to subjectively reproduce the past in the present. Freud understood this better than Jung's notion of neurotic regression. From linguistics we can also grasp the difference between synchronic and diachronic structure and see how this works when discussing resistance or transference. Freud anticipated these borrowings. We might fit them within the 'epistemological triangle' [the zigzag link between s and a?]. We might add other topics rooted in language — rhetoric, dialectic, grammar and even poetics, which might help grasp witticisms. Psychoanalysis belongs with the liberal arts, focused on privileged problems rather than formalization, helping to grasp humanity against the 'arid years of scientism' (51). The task still remains to grasp human experience, intersubjective logic, human temporality and the symbol. Section 3 Interpretation and Temporality The importance of symbolic interpretation seemed intimidating and then embarrassing to early psychoanalysis, which persisted in the early scandalous reception of Freud. Subsequent disagreements are unsurprising. Current practitioners seem to want to develop completely objectified approaches and they can attract enthusiastic support. However, they seem to be based on growing misrecognition of the subject. If we return to Freud's cases like the Rat Man, we can see that many of the subsequent criticisms of omission were anticipated. Freud understood full well that he was encouraging his patients to go beyond their experience and explore their Imaginary. The patient's distress at recounting the torture episode revealed to Freud the patient's horror at his suppressed pleasure and saw that the psychoanalyst could be identified with the original sadistic storyteller. Freud then appears to continue with the game rather than overcome the resistance, but Lacan interprets this as joining with the patient to explore the symbolism of the word, implicating the subject himself. Freud also skilfully manages the subsequent conversation where the subject got evasive. The example shows that analysis 'consists in playing in all the multiple keys the orchestral score which the Word constitutes in the registers of Language and on which depends the over determination [of the symptom]' (55). [Note 128, p. 139 explains that the score was a good example of something that could be read horizontally and vertically]. At the same time, the cure requires that the analyst's response is 'particular to him'. We have to rediscover these principles rather than literally apply Freud's terms. The principles 'are none other than the dialectic of the consciousness–of–self', developed from Socrates to Hegel, based on the assumption that all that is rational is real and ending eventually with the scientific judgement that all that is real is rational [note 129, page 139 talks about needing to conjugate the particular to the universal, subordinating the Real to the rational, in the process of which the subject will be seen as having a role in constituting the object, as in Hegel's phenomenology. The note adds that the slogan above about the real and the rational should be understood as the rational being actual, 'or effectively real' and vice versa, and again there are links with Hegel]. The process whereby the subject establishes this truth involves a 'decentring' from self-consciousness, with implications for the view that the conscious faculty alone establishes reality. Hegelian phenomenology has structured psychoanalytic technique, specifically the master slave dialectic, the dialectic of the beautiful soul, and the general relations between objects and subjects, the 'fundamental identity of the particular and the universal'. Psychoanalysis best shows the ways in which subjective identity becomes a matter of [technical] realization, with a further implication that there is a deep connection between one and the other, masked by the intrusion of individualist notions of the subject [in ordinary people as well as in psychoanalysts]. However, this has been forgotten by recent developments. The very notion of analytic neutrality implies an Hegelian stance that the truth is to be discovered already there, despite how much it is confused and covered. We can also learn from Socrates and Plato [pages 56 – 57 — pretty technical but contains a sentence: 'we analysts have to deal with slaves who think they are masters, and who find in a Language whose mission is universal, the support of their servitude along with the bonds of its ambiguity']. The point of analysis is to 'liberate the subject's Word' by showing that he is using the Language of desire [note 135, page 141 explains that subjects never really talk about themselves initially, but rather talk about the moi. Resistance shows this, where patients attempt to repress or censor the social origins of connections between signified and signifier. What the analyst does here is to introduce new discordances to establish the original censorship. In this way, the 'subject of the unconscious' the 'true subject' can begin to address himself to himself as he comes closer to the truth contained in the Word] Language is universal but it also realizes itself in particular desires of the subject. We can talk of a primary language, discovered by Freud and extended by Jones discussing symbolism [he seems to have argued that the thousands of symbols can all be traced back to the body, kinship, birth, life and death]. When symbols are repressed [unconsciously], they do not indicate their regressive or even infantile nature. They still make themselves heard, however. We see this in reactions to symbolic acts in normal as well as neurotic people [and then a diversion into Hindu traditions via a particular story, 58 – 59]. Primary symbols resemble primary numbers. We need to investigate symbolic displacements as in things like metaphors [note 139, page 143 explains that metaphors work by substituting one signifier for the other, making it take its place in a chain of signifiers, sometimes as a metonym referring to other parts of the chain. Later work talks of 'a latent signifier' as one term replaces another, in effect making the first one a signified]. This requires a full knowledge of the resources of language. Freud himself was well acquainted with German literature as well as Shakespeare. Interest in the classics and in current anthropology would also be useful, but recent psychoanalysts have not followed the same road [some English psychoanalysts seem to be rebuked here, practising ego psychology in a very limited and literal way]. [Explains his own literary style?] With symbols, words transform the subject by acting as a signifier. That's why we need to understand language and not see signs as simply the names for objects as in simple notions of a signal in a code. [However, note 144, page 144 notes that as Lacan pursues the notion of the signifier 'the less one hears about the signified']. This partly explained the recent interest in gestures or body language as supplements to the word. Can we find evidence for this in the behaviour of the honeybee and its dance? This is an example of coding and signalling, but not necessarily of a Language because there is 'the fixed correlation of its signs to the reality which they signify' whereas in a Language signs relate to each other and can show 'lexical sharing out of semantemes' (61). Nor is the message ever retransmitted, but remains fixed, permitting no detachment of the subject. Language by contrast 'defines subjectivity' by necessarily referring to social action or the discourse of the other. It invests a person with new realities by naming them. It is dialectic in this sense, requiring a response from the other even if inverted: in this sense, 'the Word always subjectively includes its own reply' (62). When Language is reduced to the functional, to information, or to the particular, it loses these characteristics. The value of Language lies in the 'intersubjectivity of the "we" which it takes on'. We see this in the residual redundancies of language even that which is intended just to be a matter of communication — what is redundant indicates [something surplus] the necessary 'resonance in the Word. For the function of Language is not to inform but to revoke' (63). The Word evokes the response of the other. My question constitutes me as a subject, but the question is already based on a desire to be recognized by the other and will include something like a name for the other. Thus as we identify ourselves in Language, so do we lose ourselves by becoming an object. Our understanding of the past is not an accurate recollection of what was but the form of 'future anterior of what I shall have been for what I am in the process of becoming'. Responses can never be predicted as simple reactions. To see a response as a reaction to a stimulus is a metaphor. A similar one attributes subjectivity to animals. The metaphor is glossed over by using technical terms. Human beings do not learn by experimenting with stimuli in order to get the right result — desire guides the response [the fulfilment of desire is the real response]. Similarly, responding to others really involves 'to recognize him or to abolish him as subject' (64). Language has a materiality as a body. Words appear in corporeal images as we see with neurotic patients who associate words with bodily fluids. They can accomplish 'Imaginary acts of which the patient is the subject' (65) [the reference is to the Wolf Man case. The examples seem to involve the ways in which the names of things like wasps transform into people's initials]. Whole discourses can become eroticised. They clearly involve suppressed pleasures in the speaker. Words become Imaginary or even Real objects for the subject, often condensing the broader functions of Language. Analysis by contrast seeks the 'true Word' and explains its relation to the history of the patient. This is dialectic, never objectifying. Freud even used suggestions strategically, whether they were materially accurate or not [again linked to the Rat Man. The goal was to help the subject rediscover in his own family history and other memories, the endless nature of the symbolic debt which he felt unable to repay and which developed the neurosis [note 152, page 156 equates the Symbolic father with the actual dead father of the patient, another example of a contradiction with simple reality]. We also see the useful role of an Imaginary person in the process of transference [apparently a daughter which the Rat Man fantasizes about marrying, knowing it was not reality]. The first step is to recognize where the ego of the patient is, already defined by Freud as 'formed of a verbal nucleus' (67), the source and the object of the question posed by the subject. Only then can we focus on the desire of the subject and the object to which it is addressed. In hysteria, there is 'an elaborate intrigue' where the ego is found in the intermediary object enjoyed by the subject. Hysterics genuinely act out, outside themselves Obsession involves dragging objects into narcissism, a form of staging a spectacle. Both of these are examples of the crucial importance of the relation between the I and the me, remembering that these are not the same as individual subjects. Ambiguities have arisen in Freudian terminology here [pages 68 – 69]. Discussion includes an understanding of psychoanalysis as a matter of two bodies in relation. The analyst teaches the subject to see himself as an object, with an illusory link to subjectivity; the Word is used as part of a search for lived experience; the subjectivity of the analyst is different from normal, however, unrestrained, and this leaves the subject open to every analytical use of the Word [very difficult material here]. This is what Freud meant when he said that everything in the id must be grasped by the ego; it must be a suitably compliant ego to assist the analysis. In other words the ego must continually split, although the egos of patient and analyst never fully coincide [since analysis itself is never ended?]. However, analysts also assume that all the formulations of the patient are defensive. Freud's discussion of Dora shows that the analysts' prejudices can themselves intervene in countertransference and that this can prevent the moves on the part of the patient to grasp the processes [Freud continually insisted that Dora really desired Herr K]. The case also shows considerable 'intersubjective complicity' when Dora, after a break, engages a second stage pretence to conform to Freud's understanding, by claiming she was pretending to be rejecting his analysis. A guilty conscience is apparent in some of the recent developments in psychoanalysis, especially if the disappearance of symptoms looks like magic rather than science. They want to reassert the traditional distance between themselves and the patients, assuming that they have a scientific grasp. This is quite opposite to Freud's own approach where careful listening and no condescension led to his discoveries, including the wider significance of the Schreber case. Analysts instead should rely on the qualities of the Word and how it permits understanding, agreeing that some things might not be immediately apparent [but that does not mean they are somehow prior to language]. And if we see these as not depending on language, we are left not knowing how to translate them, and a form of suggestion is often what results. The relation between analyst and patient becomes rather 'phantasmatic'. The illusion that sees a reality behind language is actually shared by subjects who believe that the truth lies outside them and that the analyst can discover it. However, Freud himself never saw transference as simply explicable by the neurosis: it had an element of reality. In practice, transference is 'the normal error of existence' (73) found in the very common 'love, hate, and ignorance', real sentiments. Further clarification of Lacan's own terms are required to avoid misinterpretation. Reality in analysis can often appear in a negative form and as something encountered when we attempt to actively intervene — although a refusal to reply can also be an element of reality. This sort of 'pure negativity', not tied to particular motives (74) shows the junction between the Symbolic and the Real: in effect the analyst is insisting that all that is real is rational and it is up to the subject to disclose this. The question may not involve the true Word. When it does, there is a reply already contained in it, so analysis only demonstrates the 'dialectical punctuation' involved. The Symbolic and the Real are also involved in time as we saw. The duration of the analysis is indefinite. We cannot predict the moment of comprehension. There is also an implicit 'spatializing projection' based on the assumption that the truth is already present, although this must not confirm the original understandings of the subject [maybe]. Real patients like the Wolf Man may never fully grasp the place of a primal scene in their history. Symptoms like paranoia can be understood as a form of self alienation. [More detailed discussion of the Wolf Man and his subsequent treatment, apparently discussed at length in a seminar, pages 76 – 77]. There is also the issue of the length of the session [very brief sessions particularly pissed off Guattari]. There is a professional issue here since the length of the session is working time, but there are also subjective dimensions. Insisting on a standard time is a way of glossing what is really a problem for analysis. Can the actual time required be quantified? Why should objective time dominate when it is subjective time that matters both in the construction of a symbolic object and in the momentary relapse where an analyst ignores it? There is nevertheless both labour involved and symbolic exchange [note 168, pages 148 – 9, adds a dimension of time associated with debt and its repayment, through some association with a bond as lasting word, some constant commitment. This persists even though the names of actual ancestors who need to be reimbursed may be forgotten — the pledge is what remains, and this 'maintains the integrity of social life', 150]. There is also the way in which the analyst controls the discourse towards truth. Ending a session is always experienced as a kind of punctuation in his progress for the patient, another of the delays or evasions in his discourse. Punctuation always fixes the sense, and this can prevent the conclusion of a discourse or the fixing of a misunderstanding. It is entirely inappropriate to make the ending of a session a matter of routine, although it seems to bolster the neutrality of the analyst. Routine can even assist the patient who is always ready to see the labour of psychoanalysis as forced. There is the danger of connivance with the patient, especially with obsessives who tend to see everything as forced labour. Via Hegel, we can extend the notion of the relation between masters and slaves which involves waiting for the master to die, another link with the procrastination of the obsessive, often seen in anxiety or fear about the death of the analyst. This waiting for the other is a form of double alienation since the slave also is only waiting for the master's death instead of living his own life, a form of death itself. The whole case is an example of how patients can work through their problems in order to seduce the analyst. Disdain for such activity can actually be positive. Lacan also claims that one effect of short sessions is to bring to light certain fantasies of males, emerging only after lengthy verbalism was interrupted. In this sense, the short session has 'a precise dialectical sense' (80). [There are links with Zen, another example of creative disdain which breaks discourse in order to deliver the Word. Freud himself has talked of the benefits of a negative reaction to therapy]. There is a link to the discussion of the death instinct in Freud. This work has been rejected by those who want to operate with rational conceptions of the ego [and by Guattari] and by Reich's attempt to analyze organic expressions beneath language. Instead, the death instinct is linked to the problems of language. We see this in the way in which it has to join together two contrary terms, to both preserve and then destroy life. However, we find in very early work in biology the notion that system equilibrium requires a compound of life and death. For Freud, the death instinct was linked to repetition, automatism, clearly showing that it was not just a matter of biology. We can get a clue from the central role of contradictions in Hindu myth [! Page 82. Further discussed in note 177, page 152 — it all turns on poetic meanings which can be added to apparently mundane phrases]. Freud also deploys poetics in his analysis of the unconscious and its dialectics, which will explain the importance of the death instinct. He identified two underlying and conflicting principles similar to work by Empedocles, which can generate myths of the dyad. This is what has produced a systematic negativity in the judgements of modern patients. It is like the compulsion to repeat, classically understood as a matter of 'the experience of transference': the death instinct 'essentially express[es] the limit of the historical function of the subject', an absolute and unconditional end rather than the more frequent comings to term with life, or final realizations of the historicity of the subject, a final existential possibility for Heidegger. It can be extended to a notion that the physical past is also finally over, not forgotten or not living on in its implications: this is what can only be reversed by repetition. Repetition really represents the mastery of subjectivity: it also produces the 'birth of the symbol' (83). We see this in the Fort Da game and its repetition as an early attempt to master the child's environment with activity, to overcome the passivity of the usual presences and absences of the mother. This is the moment where 'desire becomes human', a second level of desire, and it is no coincidence that it is also the moment where the child 'is born into Language'.. The subject 'destroys the object' by making it express desire only as a 'provocation' of absence and presence. Desire becomes its own object. The basic binary opposition between Fort and Da also become symbolic. The two phonemes become integrated diachronically and then synchronically and the child begins to engage in concrete discourse by saying the words. [Note 183, page 153, cites later Lacan to make an even more explicit link between the dyadic needs and the register of the signifier — '"the synchronic register of opposition between irreducible elements and the diachronic register of substitution and combination"'. Note 184 cites an early linguist on the crucial importance of binary oppositions to order psychic moments, and thus '"Duality has proceeded unity"']. We also see from the game that the desire of the child 'has already become the desire of another', already subject to domination. The game can easily be applied to partners either Imaginary or Real. Given this shift to desire and objects as provocations, 'the symbol manifests itself first of all as the murder of the thing' (84) [note 186, page 153 says this originally arises from Kojeve on Hegel, and uses phrases such as '"the mind… Is the great slayer of the real"', and argues that the mind actually continually subtracts aspects of reality from Being itself when it forms concepts as a kind of residue to explain what remains]. Humanity develops its first symbols in relation to death as soon as it grasps history. This helps human life persist, through the 'perpetuated tradition of subject to subject'. This is uniquely human, since individual animals are simply reproduced in invariable types [so another departure is required for Deleuze and Guattari on evolution eg in Plateau 3]. Any explanation of individuals deriving from a phylum 'must [still] be integrated by a subjectivity which man is still only approaching from outside'. Comparing the individual distinction between rats with the legendary and memorable acts of human beings. The notion of liberty should always be understood as something going on within a triangle of renunciation [as with master-slave stuff above]. The desire of the other is limited by death, whereas serfdom can be seen as pleasurable [jouissance, even] as a kind of 'consented–to sacrifice of his life' which will end in triumph with the death of the master. In this way, we must understand the death instinct as 'that desperate affirmation of life', a final escape from the will of the other. Thus we see death as something 'primordial to the birth of symbols' (85). An awareness of mortality provides 'a centre exterior to Language', a structure of symbolic logic, perhaps best modelled as a three-dimensional torus relating peripheral exteriority and central exteriority. Subjects realize their subjectivity both in 'the vital ambiguity of immediate desire' and 'in the full assumption of his being–for–death'. We see here that dialectic [in psychoanalytic encounter] is not just individual. A resolution must satisfy all the dimensions of human undertaking, no less than a relation between care for the individual and relating to 'absolute Knowledge'. It requires a full knowledge of dialectic operating at the symbolic level, amidst linguistic discord. [Then some wonderfully lofty and self-important stuff about psychoanalysis looking for 'the putrescent serpent of life' amid the darkness of the world, page 86]. Freud was leaning towards a biological basis for his discoveries, whereas this orients itself to culture, but these must be considered together, joined by an inner contiguity. Nevertheless, psychoanalysis has restored the role of Language as a law, and uses poetics to explain the symbolic mediation of desire. It is only through the Word that 'all reality has come to man and it is by his continued act that he maintains it' (86). [Typically, we end with a quote from early Indian religion where gods provide humans with sacred texts stressing 'submission, gift, grace']. |