|

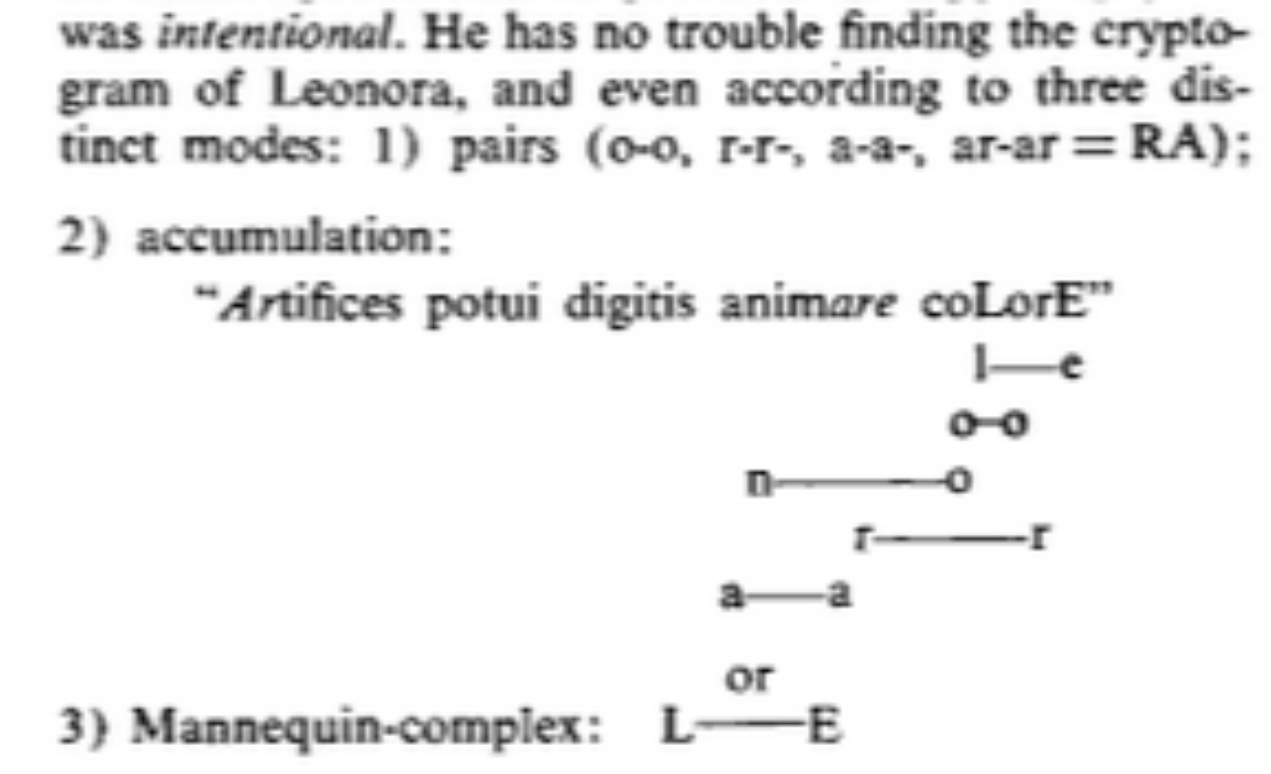

Dave Harris [I read this difficult piece only to get some background to the discussion in Kirby. I have massively glossed and vulgarised. Some terms are explained well in Kinser] Saussure developed a line of research he was worried about, into anagrams. It could be a second major contribution, or, as Saussure himself worried, a sign of insanity. In practice, it actually preceded his better-known Cours..., although the enterprises seem quite different. The one on anagrams was semisecret, 'pursued pragmatically, accumulating concrete evidence' (2), while the other was more general, theoretical and delivered as public lectures [so written vs spoken too!]. The anagrams one is perplexed, the general one about clarity and systematic formulation. The first one was inscribed in notebooks and aroused no interest at first. We have two enterprises, one laying the scientific grounds for discipline, and the other investigating 'a practice of the text' with no immediate theoretical structure. The work on anagrams is polyphonic, about undisciplined signifiers. Somehow, structural linguistics emerged from this earlier work — somehow reason had prevailed over madness, held it 'back to the limit of its own truth'. The review here locates the 'nodal points' of the anagrams piece and traces [neglected] connections with psychoanalysis. Saussure does not want to reduce the anagram just to the categories of rhetoric, and instead pursues an 'interplay of approach and avoidance'. He begins with alliteration, going on to rhyme, assonance and characteristics such as 'paranomasia (analogous signifiers, different signifieds)' and other features such as 'apophony [roughly changing vowel sounds to change meanings --'sing' becomes 'sang' etc], antanaclasis [roughly, using the same word in two sentences with different meanings -- eg 'your sound argument is nothing but sound']. The procedure seems to be to emphasise the 'correspondence of phonic elements', the way in which the same sound appears with other meaning. Poets use this to produce a definite effect, but Saussure is really interested more in any underlying laws for these stylistic flourishes. It began with finding alliterations. Whole lines can be alliterative. Sometimes there is a rigorous correspondence between them, ignoring meter. Specific differences, including those of meter, are ignored in favour of trying to get at the '"real phenomenon"', something general, an 'algebra of discourse' producing the specific articulations. For Saussure, the material of writing as such is less important than the characteristics of speech, part of the general 'anathema' on writing as artificial. However, Saussure still refers to various kinds of 'grams', written signs to designate phonics. The [process of] writing of anagrams is not relevant, and he seems to use grams for phones only to preserve conventional understandings [? see below]: The only important characteristic of writing is its use of signs. If anything, the proposal is to replace gram by phone, leaving writing as literally inaudible [and thus a poor version of speech. Nevertheless, I think the argument is that some of the characteristics of writing can still be found in the actual analysis]. Saussure's treatment of phonics as crucial elements of writing does mean that they are no longer located in Derrida's logocentric tradition, which connected voice to idealised meanings. The phone does not have some immediate presence, nor is it enclosed in the sign: it only refers back to another element which is not present. [but see Kinser] The phone as gram slides, like poetry, or a dream, not following conventional syntax but producing holes in it, permitting another kind of discourse. Thus poems are textures of correspondences, linked cores joined by signifying material. Invariably elements are going to find phonic counterparts — 'countervowels, consonants of recall' (3), a response to expectations prepared by the first term, 'a kind of exploded, disseminated, abstract echolalia'. For Mallarmé, a book consists of a collection of '"a few reiterated numerations"'. Together with a line of discourse, a counter discourse emerges, or even a non-discourse, an extravagant element, a 'fundamentally diversifying combination' implying a duplicate line, and 'a nonlinear extra temporal space where speech is lost in infinite disconnections'. However, anagrams threaten the basis of Western metaphysics, pairings balance, standard formulas and spaces, for example. [In the first method -- see Kinser] it might be possible to think of an '"ideal poetic line… Offering, for example a total: two Ls, two Ps, four Rs… And so forth'. This would be a 'preverbal trans-linguistic level in the order of discourse' [implying that numbers also have an effect of their own, or that you can deliberately manipulate language poetically, using number sequences?], further implying that numbers are not simple signs or representations, but 'artificial notations'. Using numbers like this would provide a subversive function, and one that mathematical notation has always brought to bear on alphabetical sequences, weakening them as ideology [apparently as Derrida and Kristeva both argue]. Numbers would indicate differences, regardless of specific meanings of vowels or consonants, and thus providing an independent meaning [we still talking about ordinary language or special artificial avant-garde languages? It might be the latter -- cf films like Greenaway's Drowning by Numbers?] Something like these disturbing repetitions do arise in certain examples, say of Homeric poetry. Saussure himself had serious doubts about whether he could develop a law of such pairings, however, especially if the criteria are imprecise, say if poetic meanings in the conventional sense reassert themselves. The actual phonic material is difficult to grasp, especially in archaic texts. [There is an implication that Saussure was still hoping to find proper foundations and exact proofs?]. Sometimes, he openly despaired of being able to process phonemes in this quantitative way, and he considers whether or not phonic groups might be better units — these are more easily distinguished, but equally difficult to reduce to a formula. Saussure was particularly impressed by texts where entire lines were anagrams of earlier lines, even though they might be separated by considerable distance in the text. This hints at 'the infinity of language', a 'textual process without origin', and endless 'play of referral and reverberation' (4), where every site is a citation and an incitement. Saussure abandoned this line of enquiry, however, apparently because of the difficulties of developing exact criteria. He returned instead to the more common notion of the anagram as 'a domesticated analogue' of the infinite process . He still found some interesting relations which he took to be '"independent fact — one which may be considered in an independent manner"': Polyphones tends to reproduce syllables of words or names which are '"important for the text"' [and which serve as important anagrams, almost metonyms?]. [We have to remember the whole argument turns on phonics -- anagrams are not written ones like we know them. See Kinser] Saussure never fully explores this articulation, and eventually distinguishes an internal relation, the acoustic series of phonic elements, and an external one, 'the series of meaning'. These are not put into a hierarchy, but they really show 'a particularly acute form of denial': Saussure openly hopes that someone will show simpler repetitions that do not repeat important words or proper names. The result of all these domestications is to retreat from the importance of numbers in linguistic series, generalised alliteration, and to focus any attempt to develop laws on the basis of words alone. The shift of emphasis to syllables from phonic elements is a significant change, reflecting particular interest in the 'hypogram' ['theme word'] (5). Syllables ['diphones'] cannot be counted rigorously, however [and so it is no longer clear what it is that numbers actually do, nor what, say the sum of them, actually means: Saussure can only spell out some number sequences [?], accounting for all the syllables, and hoping that something will be conjured up. It is 'like any incantatory formula'. [What follows reminds me of T Phillips' project, A Humument, to find significant words in texts by blocking out some of the words or parts of words] Every proper name [especially for people?] guarantees identity and presence, and so infinite diversity is managed 'the hypogram is deliberately placed under the domination of the Logos, seat of the word and of reason, of reason as word'. A subject is restored to the analysis, one who inspires the passage, guides it with its logos toward some reasonable unity. A knowing Cartesian subject is implied. Phonic dissemination now has 'a teleological structure'. Saussure now classifies phones and hypograms in more humanistic models — 'a mannequin-complex'[the examples based on Virgil are impossible to grasp — it seems as if Saussure discovers the proper name of Hector (Primaides) in a frequently occurring syllabogram 'primaquies', and in other texts Aphrodite emerges as a unity found in the constitutive syllables {aph, ro etc} in different words]. [See Kinser for an example of how this is shown in 'mannequins' -- little boxes] These features are not anagrams exactly because they are dispersed through the text, but again not in the usual way. Some agent guides the hypogram and reduces the possible phonic heterogeneity , but this is still not the operation of conventional reason or standard signifying. The bizarre convergences themselves are now treated as under the control of conventional naming [seen initially with proper names] , with anagrams really just imitating words. 'In the same way, Plato sees writing as a supplement to speech'. A hypogram is now a simulacrum, fabrication or disguise limiting the natural signifying practices of words. What is retained is the idea of a proper name, something directly proximate to meaning, present to itself, [so logocentric according to Kinser] while the play of phonemes is a celebration of this proper name, [and a mnemonic says Kinser] like the ways in which the name of God is written into the syllables of the text. The point of uncovering hypograms is to restore a central meaning, a 'poetic intentionality' which recovers the proper name having decomposed it first into syllables. The text must still always be derived from some thinking creator, some 'originary inscription', some unified subject, though. Saussure turns away from the notion of poetry in Mallarmé, where words themselves are mobilised and allowed to clash, producing the '"elocutary disappearance of the poet"'. This potential 'fading of the subject in writing' was a central concern for Saussure. It might be that the player is some unconscious agent, playing a pre-structured game, but the rules of language are not explicit conventions, and effective communication does not require a knowledge of them. Language is unconscious for speakers [but this is not pursued]. Saussure also saw an inevitable tension between individual speakers, language, and social institutions. Nevertheless, Saussure never called into question 'the intentionality of the subject' (6). Indeed, speech was still seen as an individual act of will and intelligence. This still leaves some factors of speech outside the system, [and thus unknown to actual subjects], but while individuals may not master language fully, they do master discourse. The weird bits like anagrams are explained in terms of resembling a game of chess again, but anagrams do not achieve the full status of facts of language and thus they are not attended to by the subject: they seem to be imposed '"naturally"' by things like the theme of the text and the pressure to express a context. Poets can sometimes deliberately use anagrams, though. Overemphasising poetry would reduce the impact of the finding of anagrams — even poets obey other rules of verse writing, and anagrams are seen as relatively imperfect compared to other operations. They are better seen as an '"incredible relic from another age"', found in ancient Greek, and still accidental, or at least lacking 'any proof of such a deliberate practice'. Eventually, Saussure came to 'suspect in the implacable signifying activity a second nature', and saw it eventually as arising from some '"psychological sociation"' [which is where he could have done with Freud] . What he never considered was 'the elocutary disappearance of the poet' [apparently, another theorist, Pascali, encouraged Saussure to take this line], and much was made of what might be seen as real or typical examples of text, when not poetry, but things like the 'business letters of Pliny or Cicero'. Using a term like sociation is still limited, and still based on the notion of the subject. We might see these days that he has provided material for psychoanalysis, the Lacanian petit object a [encounters with actual others]. If so, his grasp of linguistics was inadequate to explain it. Starobinsky puts it as a willingness to dismember the signifier, but retain the unsplit subject. The only departure from conventional understandings of language as involving a subject arises when Saussure thinks about the total body of language, something imaginary [without providing any Freudian Lacanian account of the language of the Imaginary] [really obscure discussion here based on discussions of Isis and Osiris]. Saussure could have drawn upon the recently published Freudian account of jokes, explaining the structure of 'words beneath the words and the jokes beneath the cogito'. Jokes belong in the unconscious like parapraxes, and are 'elaborated on the Other Scene' using the linguistic operations of condensation, displacement, and representability. Jokes are specific meaning effects, however. We can compare them with hypograms. Both have phonic similarities, but the joke plays with ambiguity, deliberately using one word in different ways, in puns, referring to a particular original, and offering something factitious. If we take the name Rousseau, which is an anagram of Saussure [wha? at the phonic level?] we can dissect it first as a signifier and then join the parts together again to describe one or other of them as 'roux (redheaded) and sot (stupid)' (7). We could make this into a joke by spacing out the verbal material and punctuating it differently, first minimising a particular term's value only to engage it in another term. The pleasure of a play on words consists in detecting 'numerous reverberations' in the speech, recognising that it has both an individual meaning and a halo, multidimensionality. The joke sets aside meaning at first in order to set up a difference and then offer a playful resolution. This is not what anagrams do — they only paraphrase, even when Saussure uses anagrams as 'master words' to introduce a whole new sentence. Freudian discussion involves a role for 'the mind's mode of production' [for example in people being able to guess riddles, or possibly the punchline of jokes], but for Saussure, these weird textual effects have to be studied as produced by certain conditions. Jokes are 'the most social of psychic activities' because they 'always require the presence of a third person' [a listener who can get the joke, or someone about whom the joke is being told?]. In jokes, we choose words which are innocent ['imperceptible'] by being dispersed in a text. In an anagram, it is a 'verbal perturbation' which produces a meaning. At the same time, the requirement for communication in jokes permits 'the censorship of reason', although the aim is still to look at how meanings work. This censorship appears even in Freud's own distinction between good and bad puns, even though jokes are strictly speaking not open to evaluation [because they don't actually mean anything specific]. For Saussure, any notion of play or childish pleasure is excluded at the start, and anagrams are only useful in terms of what they tell us about language. Their only point is to conceal the work of the text, for example by dispersing the syllables of sacred names. There is an implicit teleology here, although that is not detectable in actual linguistic enigmatic hypograms which is where he needs Freud, above all on dreams. However, dreams themselves do not operate with conventional meanings , and perform only transformations: anagrams think without transforming too effusively. The limits for Saussure are already clear in the status that he gives to individual words, which signify in their own unity, requiring no deformations [and displaying none because of this simple relation with characteristics and words, what Saussure apparently called a '"melodic"' form]. Saussure thinks of some primitive signifieds buried in an actual text, something with an original identity and permanence. There is no subjective distortion even for poets or analytical readers. The aim is to rescue the truth of the text from 'the oblivion of history', which applies even when there seems to be quite explicit and frequent use, say of a repressed name [see example below]. Saussure therefore partakes of a particular idealism, a perfect regression to a rediscovered origin, a return to original reality, not freudian analysis. For Freudians, however, Saussure must maintain this notion of origin and work within an idealist matrix, and this is what makes him suppress all the weird contradictions and dismemberments discovered in the actual text [and maybe reconstituting original unity is a classic phantasm? This could be where Isis and Osiris fit in?] Saussure also is led to 'perpetually defer' any solution to the problem of the hypogram (8)[although he may be alluding to something quite new about the dimensions of language? This will be the reverse of using analysis to decipher finally cryptograms by rediscovering lost language — maybe]. What are the implications for a theory of writing of this work on anagrams? We would have to see specific names as offering only a 'operative' reality, the result of a specific migration of language, a 'fictive framework' of the way language constructs meaning [when we take words at their face value, we are practically controlling heterogeneity?]. If Saussure missed a Freudian possibility to suggest that meaning is controlled by desire, there is another possibility, this time involving excess or overabundance, 'an irrepressible riddling [as in making riddles] of the manifest text'. He hints at this by asking at one stage whether or not all possible words could actually be found in every text. Certain 'unexamined propositions arising from a plausibility' shared by both writer and linguist and seen as natural would be the only explanation of particular sequences. In one of the wackier studies, apparently, [on how the Greek name for Venus -- Aphrodite-- is revealed in a Latin text,appropriately enough in a section on disguises -- see Kinser]. Saussure traces a particular name in the text, the name of a mistress of one of the characters, 'and the probable cause of his murder'. Here, he turns against the possibility of heterogeneity, even if this means abandoning hypograms unless they can be proved to be intentional. [There is an actual bit of analysis which is completely baffling -- less so after Kinser-- about how Saussure actually found the name, pairing particular syllables and involving a 'mannequin complex' [in Kinser's example, he draws a box around a word originally meaning 'ambrosial' to show it begins with A and ends with E just like Aphrodite:]  Unfortunately, this name was not actually attributed to the mistress in question, but this is no problem because Saussure argues that it is not just the deliberate intention of the writer that we should study, but something that emerges from description [de-scription], almost as a slip. However, he never systematically developed this possibility and was continually puzzled by words that apparently offered themselves up without him looking for them and without individuals being motivated to use them. He was left with coincidence, but that had to be dealt with as well in the search for some guarantees. The result was 'a neurotic protocol' [an inconsistently subjective procedure?]. Saussure did not want to abandon the normal notion of whole meaning, although he could have developed the implicit notion in these sections of a productive function found in any reading, once we go beyond the obvious constraints of linearity and conventional meaning. There could be 'other modes of significance alien to the subject-sign matrix'. Semiotics could have been developed abstractly, away from actual speech, perhaps even in the form of mathematical models, at least to calculate probabilities. Instead, the proper name is allowed to domesticate matters. The anagram remains only as an 'imaginary dimension of all writing'. The potential play on words opened dangers: that there might be something under words, some system of meaning or authority, some 'signifying economy' which apparently, Saussure found to be 'deplorable'. Saussure develops particular principles of linearity, at first as a process shifting from monophone to diphone [the recalculation of the unit that led to anagram research]. Saussure saw that diphones also imply a particular order, once phonemes are combined. This apparently indicated some fundamental condition of linearity, [one which is developed in the more conventional stuff on syntagms]. This was a necessary first step, leading to the unpublished work on anagrams, but also offering principles that were consecrated in this main model of structural linguistics [the stress on syntagm rather than a properly dynamic account of meaning production is how Kinser puts it]. This commitment to linear order provided a 'reasoning unreason' for the later work. Bataille even suggests that Saussure developed his system in order to reassure himself: the earlier work seem to be leading only to madness. So structural linguistics is 'an escape forward, a grandiose synthesis — a pyramid erected on a fundamental repression'. Things were regularised. Signifiers were bound to their signified via myth [and custom?] and this enabled linguistic science to develop. But there was still 'a small omission' which we can understand through psychoanalysis. Freud's discussion is of things like verbal inversions or anticipations in everyday life, all examples of slips of the tongue. Freud thought that linguistics was inadequate as a way to study these, especially if it focused on sounds and the way they produce changes. There was still a sense of 'correct speech' implied, and Freud saw this as the result of something external influencing speech. This is more than the [rather limited and vague] externals discovered in Saussure's work on anagrams, because the Freudian notion 'refers to the strangeness of the subject in relation to a language which does nothing but traverse him' (9) although he thinks he's mastering it. Properly pursued, Saussure could have ended with this conclusion as well, that the unconscious plays a major role in language. As it is, the analysis of anagrams prevents the full circulation of desire by limiting it using the notion of a constraining 'nominal reserve' [which seems to be the constraint exercised by accepting the proper usage of names]. In order to fully develop his analysis, Saussure should really have detached the anagram altogether from this conventional context, and placed instead in an abstract 'signifying economy'. The implications of his work could have led to a critique of conventional notions of culture, communication, appreciation of value, and emotional consumption, from the very 'ideological entrapment of the subject', as it appears in academic literature [of the kind he analysed]. Anagrams could be seen to dislocate syntax, and allow a new logic to emerge, not one of sign and representation. Academic approaches to language would then appear as 'secondary elaboration, a unifying, repetitive, fantasmatic activity' which really inhibits a more general textual process, concealing 'the labour of meaning' beneath the smooth facade. Using Saussure's work could make us suspect any written work that claims to be homogenous, and its actual working examined. The radical implications should not be confined, as Saussure himself thought, just to poetry, which is really only a 'useless luxury of the hypogram' [and in general, I think the argument is that it's not just poetry that is poetic, and that we should see poetic operations involving playing with then focusing language, anagrams, alliteration and the rest, at work in all texts]. back to Kirby |