|

Dave Harris [ I read Deleuze and Guattari before I read any Lacan, and so this highly selective set of notes relates to issues with Lacan as identified by D&G. I am only a casual reader of Lacan and my intention was solely to find out exactly what the problems were with two basic arguments that offend D&G:

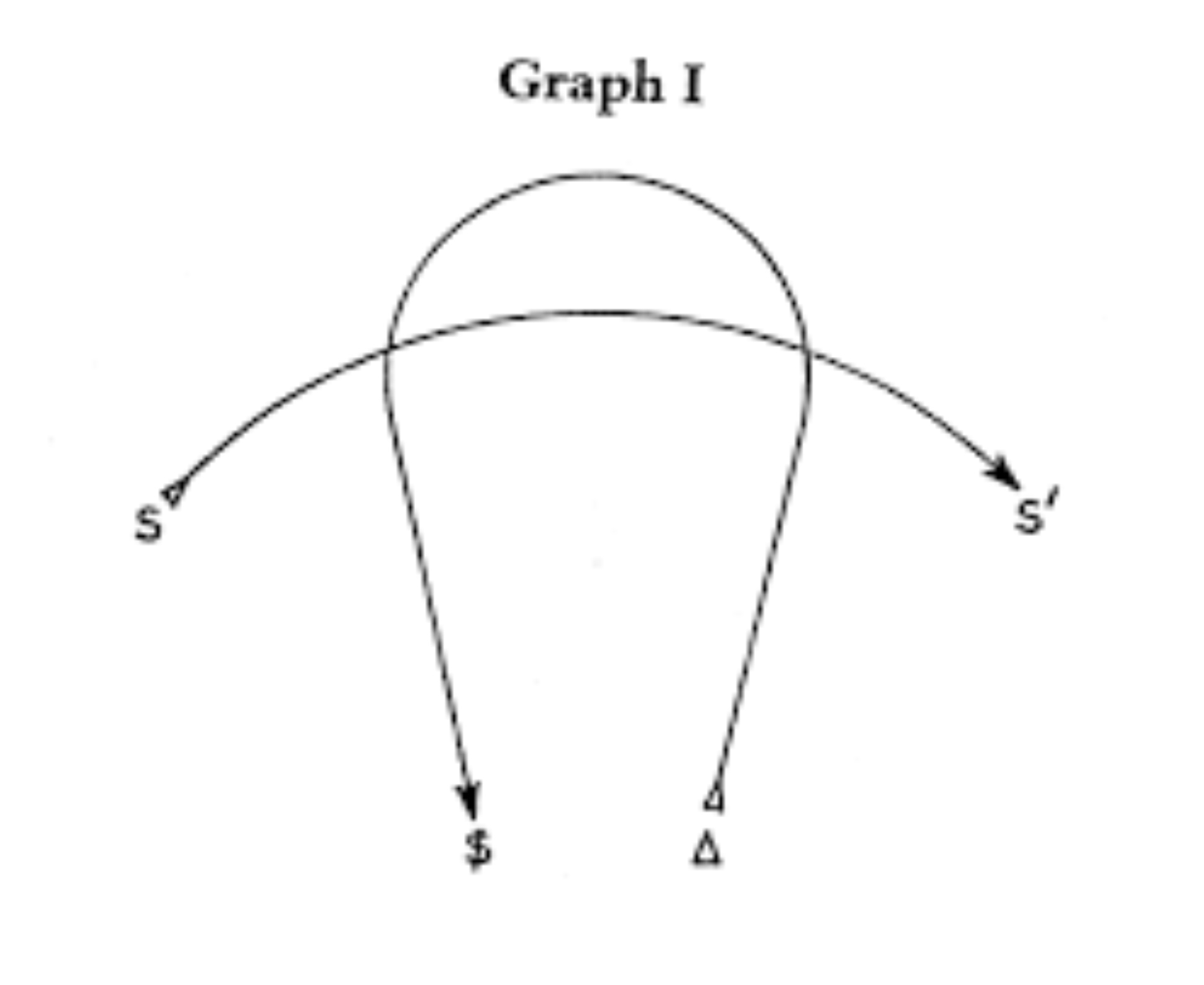

I have read Schreber's memoirs, his account of a very well-developed paranoid delusion,variously described as schizophrenia or dementia praecox. I have not taken notes, of course. I have also read Zizek's defence of Lacan against D&G,which, apart from anything else, indicates, as usual, that citing a few extracts can never be decisive in any dispute about what the hell Lacan means -- or D&G for that matter. Here is what I have found so far] The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I is revealed in psychoanalytic experience, (1949) [Classic French elite academic discourse with largely implicit references to his own earlier work and the work of others, and the free use of words in other languages some of them Freudian terms. This is obviously a limited understanding of the marvellous literary flourishes. NB male pronouns throughout as in the original] [This short piece seems to contain all the features that D and G find objectionable. There is the insistence that desire is driven by a lack of conformity between the ego and exterior surroundings including others, and the subjective distortions, alienation and aggression that this produces, and this of course is challenged especially in Anti-Oedipus with the notion of desire as something machinic rather than structured into the very development of the ego. There is also a clear intention to see psychic phenomena as linguistic. There is, however, some social criticism of narrow utilitarian societies, and pessimism about any possibility of reforming or ameliorating them] This work helps oppose any notion that the key to human personality is the cogito. Children can observe their own images in mirrors, an 'expression of situational apperception' (1), and a necessary stage in the development of intelligence. Children, unlike chimpanzees, go on to develop gestures which indicate a relation between the movements in the image and the environment, and 'between this virtual complex and the reality it reduplicates'. The infant is fascinated by his image. The stage occurs between six and 18 months, even before children can walk. There is an underlying 'libidinal dynamism' and an implicit 'ontological structure of the human world', which can be informed by an understanding of paranoiac knowledge. The mirror stage is an identification which transforms the subject: analytic theory describes it as the effects of the imago [the image as in Bergson, which reflects both subjective perceptions and aspects of the reality being imaged?]. The stage actually shows an emerging 'symbolic matrix' which includes the formation of the I, at an early stage, before 'it is objectified in the dialectic of identification with the other, and before language restores to it, in the universal, its function as subject'. This ideal I also generates secondary identifications, including those affected by normalized libidinal energy, but the main point is that this establishes the agency of the ego before any social determination. It is a fictional construction, something never reduced for individuals, related only to the actual subject coming into being, 'asymptotically' [a dictionary definition offers: A curve and a line that get closer but do not intersect are examples of a curve and a line that are asymptotic to each other]. The I therefore remains discordant with personal reality [hence the original tension that dominates the personality]. The subject sees the full form of his body as an exterior gestalt, of which he is a constituent part. It is something larger than him and it contrasts with those 'turbulent movements' that are felt as animating forces. In this way, a sense of permanence is symbolized for the mental activity of the I, but at the same time, an 'alienating destination'. It is still connected with a notion of the body as statue, haunted by phantoms or automata that seem to actually dominate the making of the external world and his place in it. In this way, the mirror image is 'the threshold of the visible world' (3). The mirrored image also appears in hallucinations and dreams, or in phenomena such as doubling, which are found in all 'psychical realities'. Supporting evidence for the effects of an exterior gestalt on the interior of organisms can be found when female pigeons develop sexual maturity when they see another member of the species, or their own image in a mirror. Locusts also change to the gregarious form when they are presented with similar images. This may have implications for our notion of what counts as beauty — 'both formative and erogenic'. However, mimicry also helps with 'heteromorphic identification' as in the significance of space and territory [references to an obscure debate about different ethological accounts here]. Paranoiac knowledge also shows a social dialectic which explains why human knowledge is more autonomous than animal knowledge in terms of 'the field of force of desire', but still determined by a notion of a limited notion of reality [as in surrealist arguments]. The mirror stage also indicates 'an organic insufficiency in [human notions of] natural reality' (4), although there is a tendency for 'a primordial Discord' to spill out, shown in a certain uneasiness and lack of motor coordination in the neonatal. There is other evidence to for the 'real specific prematurity of birth in man', as agreed by embryologists [in the course of this, we learn that the cortex can be seen as 'the intra-organic mirror']. The need for postnatal development is experienced as a notion of time and its dialectic which is decisive in the understanding of ourselves as individuals in history. In the mirror stage, we move from insufficiency to anticipation. The stages of spatial identification lead to a succession of fantasies, moving from a fragmented body image to a more total form, and finally to 'the assumption of the armour of an alienating identity'. Together this succession of 'the ego's verifications' structure the entire mental development. We still experience a fragmented body in dreams featuring 'aggressive disintegration', disjointed limbs, separated organs, just as in a Bosch painting. We also find the fragmented body in the notions of phantasms about fragility, including schizoid and hysterical symptoms. By contrast, the I itself appears in dreams as a fortress or stadium, a secure area within a contested one, the latter symbolizing the id. We also find lots of metaphors in waking life about fortifications, which can be associated with obsessional neurosis and its 'inversion, isolation, reduplication, cancellation and displacement' (5). These subjective data help us see that experience can be understood as 'partaking of the nature of a linguistic technique', but we still need some grasp of objective data to provide 'guiding grid for a method of symbolic reduction'. We can see in the defences of the ego, 'a genetic order', as argued by Anna Freud [order in the sense of a sequence apparently where hysterical repression is more archaic than obsessional inversion, which features isolation, and less developed than paranoid alienation where the individual I is deflected onto a social I]. In this way, we can see a dialectic between the I and 'socially elaborated situations'. The end of the mirror stage is a moment where all of human knowledge is mediated 'through the desire of the other'; where objects are made abstractly equivalent 'by the cooperation of others'. The main function of the I then becomes regulating dangerous instinctual thrusts. This function finds itself normalized by cultural developments. We see this with the regulation of the sexual object by the Oedipus complex. There may be an original 'libidinal investment '(6) in our activities [so earlier theorists have argued] in the form of 'primary narcissism', but this notion also reveals 'semantic latencies'. We can see this in the opposition between this original individual libido and sexual libido. Sexual libido was initially explained in terms of destructive instincts, but what the opposition really shows is a conflict between narcissistic libido and the 'alienating function of the I'. This also shows in [a necessary?] aggressivity in relation to the other, present even in acts of charity. These initial explanations prefigure the 'existential negativity' found in contemporary accounts of being and nothingness [presumably Sartrians?]. However, that philosophy, together with so-called existential psychoanalysis, sees negativity without realizing that the ego does not have a self-sufficient consciousness, that its supposed autonomy is an 'illusion', that these dimensions are misrecognised. Existential psychoanalysis operates in the current context, where societies are dominated by utilitarian functions, and where individuals' anxiety is increased by this limited but prevalent social bond [Lacan calls this a 'concentrational' social bond, which a note on p.7 helpfully explains alludes to the experiences of life in a concentration camp.] As a result, the explanations given of various 'subjective impasses' by existential psychology are paradoxical: freedom is most authentic in prison, people experience increasing demands for commitments, but also an increasing impotence to grasp or understand situations, voyeuristic or sadistic idealizations of sex, the culmination of a personality in suicide, the notion of the other that can only be satisfied by 'Hegelian murder' [total abolition of the other in the name of transcendence?]. None of these propositions apply in actual experience. Instead, the ego should not be seen as a matter of perception and consciousness or as organized by some 'reality principle', itself the result of a 'scientific [positivist?] prejudice'. We should start instead with misrecognition [I have translated meconnaissance despite the translator's warnings] found throughout the structures of the ego. That appears in denial [Verneinung], but there are other latent effects [to be exposed by reflection on 'the level of fatality, which is where the id manifests itself', (7)]. We can now grasp the inertia of some formations of the I. We can also understand the 'most general formula for madness' and 'the most extensive definition of neurosis': it will all be explained by the 'captation of the subject by the situation' [captation seems to mean at its simplest a reaching after, an attempt at capture]. General madness extends to life outside the asylum. We can understand the sufferings of neurotics and psychotics as a general set of 'passions of the soul', and when we examine the ways in which psychoanalysis seems to threaten communities, we can see the 'deadening of the passions in society'. Psychoanalysis, as a kind of modern anthropology, operating at the 'junction of nature and culture' can explain that 'imaginary servitude that love must always undo again' [Lacan describes this servitude as a 'knot']. We can't rely on altruism, philanthropy, idealism, reform or pedagogy because they are underpinned by aggressivity. However, there is no guarantee that we can bring people to see the other in their full otherness, although psychoanalytic practice may bring people to 'that point where the real journey begins'. The signification of the phallus (1958) [Intended, as with the others, to rebuke existing theories and open up new possibilities] The 'unconscious castration complex' (281) produces a characteristic knot. It produces certain symptoms found in 'neuroses perversions and psychoses', and it also develops the development of the subject. The subject is installed in an unconscious position which is necessary to identify with 'the ideal type of his sex', and to respond appropriately to [hetero?]sexual relations, and even to raise kids adequately. It seems paradoxical at first that men should adopt characteristic manly attributes only after a threat of castration. Freud suggested this would produce an essential disturbance of sexuality, with irreducible effects on the masculine unconscious and penis envy in women. There are no biological explanations. The very necessity of the Oedipus myth shows this. Nor is there some shared historical amnesia. So how did the link between the murder of the father and the 'pact of the primordial law' emerge, and why was castration the punishment for incest? The answer lies in examining the relation of the subject to the phallus. We are not talking about anatomical features here [but we might be later?] , hence we can extend the notion to women. There are four issues: (a) little girls also see themselves as temporarily castrated, deprived of the phallus, initially by their mother and then by their father in a form of transference; (b) the mother also possesses the phallus; (c) the significance of castration appears fully in symptoms only if it is seen as originating in the castration of the mother; (d) genital maturation seems to produce the phallic stage, associated with 'imaginary dominance of the phallic', and 'masturbatory jouissance', but also the localization of jouissance in the female clitoris functioning as a phallus. Genitality does not extend in the phallic stage to the idea of the vagina and genital penetration. Ignorance [of genital penetration?] looks like classic misrecognition [my speech recognition software cannot spell méconnaissance] and it may be false [meaning that it is not recognized as proper sexuality? Possibly that it is explained in a false way?]. This is why the phallic stage has been described as arising from [straightforward] repression [and not from the alienation of language?] with its functions seen as the symptoms. These have been variously seen as phobia, perversion or both. Sometimes the object of a phobia can be transmuted into a fetish. However, these accounts do not take account of current fashions for describing object relations. The notion of part object 'has never been subjected to criticism' (283) [Lacan ascribes this concept to the work of Karl Abraham]. The discussion now seems to have been abandoned, but at least it referred to Freudian doctrine, unlike the current 'degradation of psychoanalysis consequent on its American transplantation'. There are three diverse accounts. Ernest Jones in his account introduces the notion of aphanisis [defined in a note as the disappearance of sexual desire]. He does identify the problem of the relation between castration and desire, but does not see that this might help us develop some insight [maybe — a contorted sentence with lots of conditionals and double negatives]. His attempt to use a letter written by Freud in justification is 'particularly amusing'. He appears to make a case for re-establishing an equality of natural rights between men and women, concluding with a biblical quotation that God created them equal. He tries to see the phallus as a classic part object, something inside the mother's body, but fails to see that this view originates in infantile fantasies during an early Oedipal formulation. What produce the paradox for Freud? He failed to articulate it adequately, so it is not surprising that followers lost their way. Lacan's own commentary arose from his own interest in using the notion of the signifier, opposed to the signified as in modern linguistics to grasp analytic phenomena. Linguistic notions like this postdate Freud, but he has anticipated their formula. Freud's discovery helps us grasp the full implications of the opposition between signifier and signified: the signifier 'is an active function in determining certain effects' and the signifiable 'appears submitting to its mark' by becoming the signified 'through that passion' [The essay on the meaning of the phallus, cited below says that this also explains the incessant 'sliding' of the signified under the signifier]. We have to refer back to Freud designating the unconscious as 'that other scene' which has effects. We can discover these by looking at that 'chain of materially unstable elements that constitutes language'. Effects are determined by the 'double play of combination and substitution in the signifier' as in metonymy and metaphor, 'the two aspects that generate the signified'. These effects determine the 'institution of the subject'. We can derive a topology to replace the simple description of the structure of the symptom. It [does he mean that it which is also called the id?] speaks in the Other. The Other is a locus evoked by speech involving any relation allowing intervention by the Other. That it can speak shows that the subject 'finds its signifying place' before any signified is actually specified. This shows us that the subject is constituted with a definite 'splitting'. We see the function of the phallus here. The phallus is not a fantasy, not an imaginary effect, not just an object of any kind. It 'accentuates the reality' of any relation. It is never just the biological organ that it symbolises. Freud's a reference to an ancient simulacrum [the royal sceptre or other phallic objects?] is not trivial. The phallus is a signifier. It leads us to the interest subjective dimensions. It is intended to 'designate as a whole the effects of the signified' conditioned by its presence as a signifier. This presents produces effects. When man speaks, his needs 'are subjected to demand, they return to him alienated' (286). Speech involves turning needs into 'signifying form as such' and this can be emitted from the locus of the Other. This is a primal form of repression of needs, but it also gives rise to something that appears in man as desire. We know from analytic experience that desire is 'paradoxical, deviant, erratic, eccentric, even scandalous' compared to need. Under pressure from moralists, sometimes psychoanalysis tries to reduce desire to need. A proper analysis would start with the notion of demand, which is always connected to frustration. It is not just a demand for satisfactions. 'It is demand of the presence or of an absence', seen in the primordial relation to the mother. It constitutes the Other as something privileged in satisfying needs, something that can deprive needs of their satisfaction. This privilege does not extend to the Other being able to give love. Instead, demand can see any particular thing as proof [or denial] of love, and the satisfaction for needs as a crushing of the demand for love [a way of placating demands for love?] [apparently there are illustrations in accounts of child rearing]. This places particular satisfactions beyond demand, although they still preserve traces of the unconditional demand for love. Desire offers a less absolute substitute for this unconditional demand, permitting particular needs to be satisfied without having to meet any absolute proofs of love. Desire works by subtracting the appetite for satisfaction from the demand for love, by splitting them. Sexual relations take place in this 'closed field of desire' (287). We find the same enigma in sexual relations, a double signification, both a demand for needs to be satisfied as a proof of love from the Other, but also a cause of desire, for both subject and Other. This is what lies behind all the distortions appearing in psychoanalysis. It is disguised in sexual conduct by displacing it onto genital activity and developing an notion of tenderness which is an orientation to the Other. This is well-intentioned, but 'fraudulent nonetheless', despite being supported by various moralizing activities by French analysts. Man can never be whole or have a total personality. He is doomed to constant displacement and condensation when exercising his functions. This shows he is 'a subject to the signifier'. The phallus is the privileged signifier joining 'the role of the logos... with the advent of desire'. This signifier is 'the most tangible element in the real of sexual copulation, and also the most symbolic', literally equivalent to the logical copula. It's turigidity also 'is the image of the vital flow as it is transmitted in generation'. However, it can only act behind a veil, as something latent just as anything signifiable does when it becomes a signifier. This is shown by what follows when it is unveiled, as in paintings in Pompeii, or when it disappears accompanied by shame. It acts to 'strike the signified' in a 'signifying concatenation' The establishment of the subject by the signifier is complementary, and lies behind the splitting of the subject and its completion in an intervention by a signifier. Thus the subject organizes his life by striking [in the sense above?] everything he signifies in a drive to be loved for himself. And what is found in primary repression [as above?] can be signified just as the phallus marks the signified, '(by virtue of which [which demonstrates?] the unconscious is language)' (288). Overall, the discussion of human development is so lengthy that's we can only use 'the phallus as an algorithm', and 'rely on the echoes of the experience that we share'. The phallus as a signifier means that it is located in the Other and that's where subjects can access it. However, it appears 'veiled' as 'ratio an indication of proportion? [reason for? Rationalisation of?] of the Others desire' [note that when Lacan introduces the term ratio, just above, he refers to a musical term, the '"mean and extreme ratio" of harmonic division']. This implies that the Other must also be recognised as a subject, also split by the act of signifying. We can find some support for these views in work on 'psychological genesis'. Klein notes that the child sees that the mother contains the phallus, for example. The main point is that development is ordered by 'the dialectic of the demand for love and the test of desire' (289). [according to the author of the Meaning of the Phallus: 'To the extent that signifiers are able to articulate this thrust {the drive to express needs in signifiers} , the result is a series of demands. To the extent that they cannot, the dynamic movement remains operative but is now subject to a continual displacement whose pattern is unconsciously structured, and it is in this form that it goes by the name of "desire." Sex is important because it is the primary location for this] The signifier of desire must not be alien to the demand for love. Thus we see that if the desire of the mother is seen as signified by the phallus, 'the child wishes to be the phallus in order to satisfy that desire'. In other words, relating to the desire of the other involves the subject being content to try to offer anything that may correspond to the phallus, whether or not the child actually has a phallus — 'the demand for love... requires that he be the phallus' whatever the reality [difficult stuff here]. This initial attempt at a satisfying relation can be seen as a 'test of the desire of the Other'. The subject learns not only that he may not have a real phallus, but that the mother does not have it. This moment is crucial for the development of any subsequent symptoms like phobia or consequences like penis envy attached to the castration complex. This is where desire is connected with threat or nostalgia, because it is focused on the phallic signifier. At this stage the father also introduces 'the law' and the way in which has since done can affect the development of symptoms or consequences. The function of the phallus also shows us 'structures that will govern the relations between the sexes' [so this is the controversial bit where conventional relations between the sexes are justified as being somehow natural or an inevitable part of the normal development of the personality]. The relations turn around either being or having and when referred to the phallus as signifier, this can produce two opposed effects — 'giving reality to the subject' on the one hand [the signifying dimensions of the relation], and on the other hand 'derealising' [not grasping or avoiding or managing their reality?] the actual relations which are to be signified. A notion of 'seeming' replaces the notion of having. This protects those that have [the phallus or the penis? There are several confusions of the two?], and will 'mask its lack in the other' [note we are shifting to small 'o's]. This projects all the 'ideal or typical manifestations [value judgments here] of the behaviour of each sex, including the act of copulation itself, into the comedy'. The demand for sexual satisfaction 'is always a demand for love', with desire reducing to demand. This seems paradoxical but it explains why sometimes women 'will reject an essential part of femininity, namely, all her [natural? biological? conventional?] attributes in the masquerade' (290) in order to be a phallus, a 'signifier of the desire of the Other'. In order to be desired as well as loved she has to be something 'which she is not'. She will find the signifier of her own desire in the body of a male partner, from whom she demands love. The actual organ which has a signifying function 'takes on the value of a fetish' [only heterosexual coupling is acceptable in the demands of love?]. The actual experience of love for women deprives her of the signifying power of possession of the phallus [maybe] because her desire converges on the male phallus/penis. That also explains why the lack of satisfaction in women, 'frigidity', is 'relatively well-tolerated', and why they feel less of a need to repress desire [very puzzling, and of course, politically highly dubious — women do not need to repress their own desires, because of their attachment to heterosexual coupling which implies that men can manage it? Or that they are more interested in the demands of love and less concern to locate that in satisfying heterosexual conduct?]. For men, however the connection between demand and desire, as Freud noted, lead to 'a specific depreciation... of love'. Men find satisfaction of the demand for love in heterosexual relations. For men, the signifier of the phallus suggests that the relation between desire and the demand for love in women is constituted by his activity [again assumes a confusion between phallus and penis?]. However, the male desire for the phallus will transfer this to other women who offer other signifying possibilities 'either as a virgin as a prostitute' [very weird and apologetic stuff]. There is therefore 'a centrifugal tendency of the genital drive in love life', but this is not all good for men — impotence is more difficult to bear, and the repression of desire becomes more important [if men are to be monogamous?]. This is not to argue that infidelity is 'proper to' the male function [it is the emphasis on function which we might use to defend Lacan against a simple support for patriarchy?]. Women can also experience 'the same redoubling', although the partners of unfaithful women find it difficult to become the 'Other of Love as such', especially if they also see themselves as a substitute, especially if 'he is deprived of what he gives' [that is, rendered as some object of love, not just as someone seeking to satisfy his desires? I can't help thinking that this only makes sense given the underpinning cultural understandings of the French educated petit bourgeoisie towards adultery] Male homosexuality is a matter of desire. Female homosexuality 'as observation shows' arises from a disappointment that only reinforces the demand for love. There is a need for further examination of this difference, especially as refusals of demands are sometimes resolved by 'a return to the function of the mask' as a form of identification. Femininity finds refuge in this mask. The repression inherent in the 'phallic mark of desire' can make human virility 'itself seem feminine'. We can also examine another characteristic only hinted at in Freud. He says there is only one libido, and that is masculine in nature. The most profound thing about the phallic signifier, as the ancients realized is that it is embodied [in phallic symbols?] [and at this point we end with two infuriating Greek words!! —they might be 'phallos' {phallic pillars} and 'hermai' {representations of Hermes, messenger of the Gods so associated with language, as an erect penis. Thanks to the anonymous author(s) of The Meaning of the Phallus a very thorough discussion of this essay and others in Lacan, collected in No Subject: an encyclopedia of Lacanian psychoanlysis ]. So -- modern societies also embody the phallus in actual penises, models of them, phallic symbols and the like? Lacan himself is not equating the two but suggesting that ordinary folk still do so? The function and field of speech and language in psychoanalysis [A massive piece of work,which I have {eventually} read in a separate publication here, and which includes substantial explanatory notes] [Then I shifted to a second-hand copy of Lacan, J. (2006) Ecrits. The First Complete Edition in English. Trans B Fink. London: W Norton and Co Ltd. The volume also has a useful classified index of the concepts, necessary because of Lacan's habit of joining together various concepts in different actual sections. I've added a few additional notes from these entries] The first section is a Seminar on "The Purloined Letter". It is typically forbidding and inaccessible. I don't know how to summarize it in any detail, so I can only offer a quick prosaic summary of the main themes as they struck me at the time. First of all you have to read Poe's story about the purloined letter. To be brief, it is a story that the Queen of France has received a letter with some embarrassing and compromising information in it. She is reading it when she is visited by a Minister. He sees that there is something about the letter and decides to steal it, quite openly, replacing it with another letter face down. The Queen knows that he has stolen the letter but is afraid to say anything because she would have to disclose the contents of the letter to the King. We never know what is actually in the letter. The Queen asks the Prefect of Police to reacquire the letter. He is a typical thorough policeman and organizes a very systematic and detailed search of the minister's apartment, looking into books and probing furniture, and even searches the minister himself on some pretext. There is a suggestion that the Minister himself actually collaborates, arranging for his apartment to be vacant for a few nights. He finds nothing and takes the case to a private detective. The detective tells him to come back in a few days, produces the letter and claims the reward. What he has done is to visit the Minister and look around the apartment, having decided that the letter will be hidden in full sight. He finds it, thinly disguised, and on open display, retrieves it, and leaves a duplicate. On the duplicate he writes a Latin tag that refers to identical twins thinking alike. En route, we have some learned discussions about the rival merits of poetry and systematic scientific applications, and we learn about the French game of odd and even, which looks rather like the Cornish game of spoof — you have to guess whether your opponent is holding in his hand an odd or even number of coins. The trick is to estimate the cunning of your opponent. If you guess wrong first time, you have to decide if the opponent is simple enough just to alternate next time, or cunning enough to decide to stick with the same choice, thinking that you will be stupid enough to assume that he is stupid enough just to alternate. Lacan subjects this story to detailed analysis, drawing attention to all sorts of refinements of the plot, and commenting on the difference between the translated and original texts. The whole aim is to show that the structure of the story tells us something about the relations that lie at the heart of subjectivity. There seem to be two main points: First, if we consider the letter as the subject, it is clear that when this subject interacts with all the other participants it completely changes their lives and constitutes their own subjectivity. The minister who has stolen the letter becomes obsessed with it, falls under its spell, lets it dominate his entire purpose, and, if he decides to go public before discovering the letter in his possession is a fake, will be ruined. The letter also confirms central trends in the subjective identities of the Prefect and the detective. It is in the interaction between subjects that we find the construction of subjectivity. The actual signifiers that are exchanged -- piece of paper, actions or words --mean nothing (except at the level of the Imaginary) until they are connected to the Symbolic level. Once this happens, the full resources of the Symbolic are deployed -- the assumptions about character, the merits of poetry and science, allusions from Latin tags. Second, an astonishing and largely incomprehensible supplement to the seminar talks about the statistical possibilities of three coins showing patterns of heads or tails. I cannot follow the mathematical reasoning here, but it is apparent that these patterns follow laws of probability, sometimes with counter-intuitive results. Lacan seems to want to argue that this is an example of a mathematical structure underpinning what looks like freely chosen behaviour, or simple attempts to manipulate chance. It seems simpler if you accept his view that binary choices dominate 'free choice', which he argues arises from the basic binary between Fort and Da in the mirror stage. This pattern would explain sequences far beyond the two governed by cunning in the odd/even game -- that sort of reasoning only helps you guess the early stages (which is why if you are playing spoof you must insist on carrying on past the first 2 or 3 rounds before paying out). If this is anywhere near, what he's arguing is that there is a mathematical structure as well as the classic linguistic structure we are used to: I suppose those two are compatible if we think of the mathematical structure as representing all the possible combinations of phonemes, and the cultural one as restricting the possibilities. It it is classic academic discourse with all sorts of cultural allusions and assumptions as well as assuming we are all familiar with Poe and Baudelaire's translation. As examples, try these little beauties: … When [Dupin -- the detective] recalls without deigning to say any more about it that "'ambitus' [doesn't imply] 'ambition,' 'religio' 'religion,' ' homines honesti' a set of honourable men," who among you would not take pleasure in remembering… what these words mean to assiduous readers of Cicero and Lucretius? (14).The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious (1960) [Particularly helpful in my quest to find out why Lacan is so keen on structuralist notions of language. I have much vulgarized this elegant text, and even replaced Greek terms with their cliched equivalents] The structure of psychoanalysis as a praxis is what is important ['not immaterial']. It is some philosophical relevance for Hegel's schema in The Phenomenology… This will help us see how the subject is related to knowledge, and how the ambiguities are evident in modern science and its applications. The scientist himself is obviously a subject coming into an already constituted world, who must know what he is doing but does not know what might be the effects of science — here, he's at the same level as nonscientists. Some 'entirely didactic references' (672) to Hegel might be helpful, at least in correcting the mistakes made in psychoanalytic theory if not practice. In Anglo-American psychoanalysis, different practices in those societies have had effects — 'notorious deviations in analytic praxis' [the domination of liberal, utilitarian, positivist conceptions?] It is clear that we cannot 'condition' science by empiricism. It is also clear that so-called scientific psychology has actually developed. However, when we examine what Freud meant by the subject, this will raise serious problems with such an 'academic framework'. The main flawed assumption is the unity of the subject, supported by an interest in a certain notion of consciousness and by attempts to develop an organic basis for psychology. One problem is that there are clearly varied states of consciousness including religiously enthusiastic or hallucinogenic ones, and these are difficult to tie to [positivist] theory, despite seeming to be natural. Hegelian approaches also tend to ignore these states, especially in terms of how they might be seemed to generate knowledge or insight into the working of the mind [via an '"epistemogenic" or "noophoric"' 'ascesis', of course!, 673]. So does Freudian practice, but in Freud's case, that was because they did not cast any light on the workings of the conscious — that's why 'Freud prefers the hysteric's discourse to hypnoid states'. It is difficult to convince these theorists of the need to really interrogate the unconscious, and to see in it a logic, an interrogation or development of an argument. Grasping that will lead to an understanding of the human subject. Psychoanalysis has always warned against an early intervention of the analyst's voice. There can be no support for the view that Freudian practice will lead to an understanding of 'some archetypal or in any sense ineffable experience' (674). [A dig at Jung -- but also applicable to modern exponents like the posthumanists, or what Lacan has called the proponents of subjectless 'affect'] What was Freud's Copernican step? As with Copernicus, it is not just that one privileged centre should be replaced by another. [There is a sub- theme here that the triumph of Darwinian evolution has mistakenly done just that]. Other more insightful approaches tend to be rejected [one problem with Darwinism is that humans still believe themselves to be 'the best among the creatures'. This is an example of an 'idiotic notion stemming from the religious tradition' as is naive heliocentrism]. We need closer ties between knowledge and truth [rather than a regime of 'double truth' — pass. It might mean something to do with science being more interested in internal validity than truth?]. Psychoanalysis offered a seismic upheaval ['a new seism'] comparable to the birth of science. Hegel might be able to give us an ideal solution involving the idea of a truth constantly being reabsorbed, truth which is self-sufficient but which is limited by the particular stage of the 'realisation of knowledge'. Knowledge has to press on with resolving its ignorance. Again we have a tension between the imaginary and the symbolic in his terms. A convergent dialectic proceeds until it is able to finally join the symbolic with a fully grasped real. This is equivalent to 'a subject finalised in his self-identity', which in turn implies that the existing subject is capable of such attainment, 'already perfect(ed) here'. It is the 'wholly conscious self' coming to being that lies beneath the process. However, the actual history of science shows the importance of various detours which are far from consistent with immanentism. Nor do scientific theories themselves fit neatly into thesis and antithesis. The search for truth must be independent of consciousness here as in elsewhere. Perhaps science is currently warming towards psychoanalysis for this theoretical reason? [Or proceeding as if there were no knowing subject, possibly] We might see this with psychology and its links with psychoanalysis, but reinvigoration is not likely in that case. Hegelianism understandings at least support Freud in his attempts to develop a truthful science as well as a praxis which shows how truth is repressed. We see this in the connection between the unhappy consciousness in Hegel, and the discontents of civilisation in Freud: both refer to 'the suspension of knowing' (676) In Freud, it particularly refers to 'the skewed relation that separates the subject from sex'. Certainly, Freud owes nothing to the forces that inspire modern psychology ['judicial astrology']. Nor is it a matter of phenomenology. Indeed, 'consciousness is a characteristic that is...obsolete to us': the unconscious is not just the negation of consciousness, nor is it affect, a 'protopathic subject... a function without a functionary'. Instead, 'the unconscious becomes a chain of signifiers that repeats and insists somewhere (on another stage or a different scene, as [Freud] wrote) interfering in the cuts offered it by actual discourse and the cogitation it informs.' The signifier is the key, as in modern linguistics, associated with Saussure and Jakobson, and early Russian formalists. Linguistics is not available to Freud, but what he calls the primary process, governing the unconscious, corresponds to functions identified by linguistics — 'metaphor and metonymy — in other words, the effects of the substitution and combination of signifiers in the synchronic and diachronic dimensions respectively' (677) [I must say I had always taken the key aspect of a metonym as the way in which it condenses qualities into a part, but this clearly must operate in the diachronic dimension in discourse?]. What notion of the subject ensues? The linguistic definition of I as signifier suggests only a 'shifter or indicative', where grammatical subject of the statement designates the subject — the enunciating subject. However this 'does not signify him'. There may be no signifier of the enunciating subject in a statement, and there may be other signifiers that do not refer just to enunciation but more to the 'first person singular', or its plural versions. In French, the enunciating subject might appear in the signifier 'ne', an expletive [apparently it can be used to indicate 'not but'and thus to mean a particular I, or a particular person being criticised — obscure example with lots of subjunctive verbs, the difference between 'they could not but come to vilify me' and 'they come to vilify me'. Maybe in the second version we lose the specifics of the case?]. The issue is to work out who is speaking in psychoanalysis, how the unconscious can present itself as a subject, in cases where the actual patient 'doesn't know what he is saying'. This emerges crucially in the space between two subjects and what is said there. The Freudian subject shows 'occultation by an ever purer signifier' (678). We know this from slips of the tongue or jokes, or even more elusive forms of elision. It is been ignored by existential psychology though ['the hunt for Dasein']. Discourse can be seen as offering a series of cuts [meaning interventions?], especially one that puts a bar between signifier and signified. Here there might be some sort of preconscious subject at work. We might think it worth interrupting this discourse, but psychoanalysis is already an interruption, 'a break in a false discourse', empty speech. The signifying chain 'verifies the structure of the subject as a discontinuity in the real', hence psychoanalysis's interest in 'making holes in meaning' to energise its own discourse. We see this in the famous statement by Freud: 'Where it was, shall I be', [apparently 'a famous declaration by Freud about the relation between the unconscious and the conscious', according to an {unlinkable} Encyclopaedia of Lacanian Psychoanalysis]. In French translation, we get a sense of 'where it was just now, where it was for a short while', implying that 'I can... come into being by disappearing from my statement...'. This is 'an enunciation that denounces itself, a statement that renounces itself… an opportunity that self-destructs', leaving an idea of what must be beyond human being. In a dream analyzed by Freud, we find a dead father returning as a ghost. The image has pathos because the father did not know he was dead. This resembles the subject's relation to the signifier — we have an enunciation which casts the status of the subject into doubt. Perhaps none of us exist except in so far as no one else tells us the truth of which we are unaware. In the dream, the patient preferred to die rather than tell the truth to his father, showing himself to be a proper subject, moving from 'where it was (to be)' (679). The subject comes on the scene as 'being of nonbeing', always risking his sense of himself being abolished by knowledge, [real nasty form of alienation this] and situated in a discourse 'in which it is death that sustains existence' [a massive generalization indeed]. Hegel admitted that his scheme ending in absolute knowledge risked madness. The Freudian example above checks that by exposing the inner 'vanity' of claiming knowledge in discourse. At the root of the question is a difference between the dialectics of desire in the subject and in knowledge. In Hegel, desire is what keeps subject building on antiquated knowledge. This is the cunning of reason [where subjects think they act from specific personal impulses but serve the more general purposes]. If this desire to know gets 'bound up' with the Others desire, we can get 'the mobility out of which revolutions arise'. Freud has biologistic arguments, but a full grasp of the death instinct is crucial to understand them, despite the current rejection by others. We should understand it as 'the metaphor of the return to the inanimate' (680). It refers to a margin beyond life that we recognise from our language use [something external and post-dating us?]. At this margin, both parts of and the whole body take up a 'signifying position'. [the body puts itself on the agenda as it were, makes us fully aware of its constraints?] External objects can become 'the prototype of the body's signifierness', rather than being understood as partial identifications. Freud's concept Trieb should be understood as a drive, or even a drift, and urge or pulsion, but not an instinct. We can understand the form of knowledge normally thought of as instinct as 'a kind of [experiential] knowledge' which can never be fully articulated, but this is not what Freud is interested in. His analysis is based on a discourse which is unknown to the subject. The unconscious has very little indeed to do with physiology. Scientific psychology has contributed nothing to psychoanalysis, even in its study of sexuality. Psychoanalysis concerns both 'the reality of the body and of its imaginary mental schema'. Psychological development traces at best the ways in which 'fragmented integrations' emerge. It is better understood as 'a heraldry of the body'. There are implications for the privileged position of the phallus — never just a part object. Criticising scientific psychology is the reason for drawing upon Hegel's work, not a full attachment to the Hegelian dialectic. There is no 'logicizing reduction'in desire, no way to reduce desire to demand or need. Desire is articulated, but not as a psychological discourse [he hints that it might be better understood in an ethical one] (681). We can discuss these arguments by looking at a topology, graph [diagram in the usual sense, but maybe with deleuzian hints as well] that he has worked on. There are different levels to analytic experience. We can see how desire is linked to a subject who is articulated by the signifier.  The signifying chain runs from S to S'. The other vector runs oddly from right to left [I'm going to use words like barred or split subject {of which more below} and Delta -- the sign,apparently for the 'primitive subject of intention' [according to the Nidia Reading Group piece, the {infantile?} subject acting on needs]. When they intersect, there is a '"button tie"' [apparently as in quilting] . One of the things this shows is how 'the signifier stops the otherwise indefinite sliding of signification' [because it bumps into something that is of unconscious importance? Because it encounters otherness that helps it confirm and complete as below? First one then the other? ]. These intersections are commonly buried underneath empty or pre-text. As a sentence develops, it crosses this other vector twice, finally closing the signification, but also showing a moment of anticipation which can have a retroactive effect. There is also a synchronic structure of metaphor, emerging with infants at the very moment at which they can disconnect the thing from its most obvious characteristics [the example is the playful statement that the dog goes meow, the cat goes woof woof]. Here the sign becomes a signifier, and reality gives way to 'the sophistics of signification' (682). [I think this means that there is more flexibility than would be provided by simple mathematical combinations of the points, as in the 'topology of a four corners game']. Similarly, there is a need for 'multiple objectifications of the same thing' to be verified. We can examine in more detail the two points of intersection:  From what I can see, other symbols are used to illustrate other possible problems to solve, using the underlying structure. So, according to Ross : I(O) = ego ideal; s(O) = signification of the other (should be O-type other surely?); e=ego, i(o) = specular image; O=the Other. [I now think the difference is that the diagrams are offered in at least two version -- those I found on the Web, are the ones from Seminar VI: Desire and its Interpretion I am reading them in Ecrits which is later. I hope the terms might just reflect different levels of translation? -- in Ecrits we have m not e and i(a) not i(o) -- so English versus French versions of ego/moi and other/autre?] The point on the right [the first one in this back-to-front scheme], O, provides us with 'the treasure trove of signifiers'. These signifiers need not relate to codes or things at all, but work only because they are organized as binaries, in opposition to each other. At the second point,s(O), signification of the Other, signification is finished [objectified?]; so one junction is a locus or place and the other a moment in a process, a 'punctuation'. Both depend on the signifier, necessary or required, developed from 'the hole in the real', the one that reveals concealment, and the other that attempts to re-categorize. The subject submits to the signifier [and this is shown by the arrow between left and right points]. ['Voice' is specified as a particular outcome of this process?]. This is however virtually a circular process because an established assertion is initially unable to focus on anything to gain certainty. Instead it seems to offer an anticipation of being able to compose a signifier [which may be a-signifying in deleuzian terms?] The subject makes an assertion but one which cannot be closed off and made certain: it cannot avoid a certain 'anticipation in the composition of the signifier'(683)[ not least because all sorts of signifying chains are implied?] . The closure is provided by the confirmation of the Other in completing the signification? This is a circular process because an established assertion is initially unable to focus on anything to gain certainty. Instead it seems to offer an anticipation of being able to compose a signifier [which may be a-signifying as yet in deleuzian terms?]. Completing the process requires 'the signifying battery installed in A [or O in this diagram]' (683) the symbolic Other [technically the symbolic locus of the Other]. In this way, the Other can appear as a pure subject [e in the above, m in my version] as in modern game theory. [?] It helps the real subject calculate combinations, without taking into account any 'so-called subjective (… that is psychological)' factors. However, there is still a distance between the real subject and the signifying circle, a lack, since the subject thinks of himself only as something that has been subtracted from the circle.[ Something located on a line between the signified Other and the ego ideal? Which is the same as the ideal Other?] The Other is the 'site of the pure subject of the signifier', and has a dominant position even before that is consolidated by social relations, because the Other provides a code within which acceptable speech is possible. This is simply ignored in the 'platitude of modern information theory' [with its separation of S and R] because to use a code already implies that we have received that from the Other, 'even the message he himself sends'. Messages like this constitute the subject. In psychosis, this sort of communication with the Other takes a pure form. The Other also guarantees the truth. Speech itself is so deceptive that sincerity is not separable from simulation ['the feint']. Animals can change direction as a lure when hunted, but this is different from human activity: 'an animal does not feign feigning' [it cannot play at the second level, where true tracks are to be taken as false] nor can animals deliberately efface their tracks, because to do so would imply that they are able to subjectively interact with signifiers. For speech to become true speech, it requires 'the locus of the Other, the Other as witness' (684), something clearly located elsewhere. This is the real guarantee of truth, not its simple correspondence with reality, and the origin of fictional truths. Our first words 'decree, legislate, authorise, and are an oracle'. They convey authority on a real other. This is the process at work in the formation of the ego ideal, and also the first form of alienation in this first identification. We see this with graph II. Note that the barred subject is now the origin of something and not a product. What the graph also depicts is 'a retroversion effect'. The subject becomes something after [coming to recognise himself in?]stages or events, although this can be anticipated in the future perfect tense [he will have been something]. This is also an important kind of misrecognition, one which is essential to knowing oneself. We see this in the mirror stage, where an anticipated image which we see in the mirror comes to meet us. The anticipated image is all that we can be sure of. As with the mirror stage, we have to reject the notion of the 'supposedly "autonomous ego"', and the attempts to bolster it in a psychology devoted to adjusting people to American life. The altered image of the body becomes 'the paradigms of all the forms of resemblance' (685). It also involves us in narcissism, because we project this image onto the world of objects. This is also the basis for aggression. The ideal ego [I(O)] becomes fixed. This fixity takes place in a situation of mastery and rivalry, but this is disguised in ordinary consciousness, where the indisputable existence of our ego is not seen as emerging from a process, but as something transcendent, unary. This also makes it inevitably relativized, in a form of permanent misrecognition, or imaginary process The same process can be seen in the connections between specular image and constitution of the ego [in the additional vectors added to graph I -- i(o) to e in this version]. The vector here is 'one way but doubly articulated', as a short circuit from below, the longer loop between the barred subject and the ideal object, and from above [from s(O) to O]. [Note that O and the barred subject are still the sources.] What all this means is that the ego is not just constituted as the speaking I of discourse but also as 'a metonymy of its signification' when it engages in more concrete relations with objects and others. [so these concrete relations also take the form of linguistic activity]. What people like Descartes have not grasped is that the signifier plays a crucial role, but that this is less visible than the apparently transparent activities of the I in action.[what does the I think with exactly?] Lacan thinks there is an inherent aggressiveness in these relations between self and other object, that the relation between things that resemble each other is by no means balanced or in equilibrium, as in the [universal? inevitable?] relationship between master and slave: we can also find ruses of reason. In Hegel, this is a myth of slavery leading to freedom. What energizes this struggle for dominance is [really] 'a struggle of pure prestige' (686). Life itself may be at stake [always for Lacan?]. The struggles also energize 'specular capture'. We need also to consider death, which would obviously cancel any advantages of slavery and must be regulated. Therefore a symbolic pact both precedes and perpetuates violence, dominating the imaginary elements. This argument raises yet a further problem, though because death can both be brought by life and can itself bring life. Hegel can be criticized for omitting any notion of a social bond that would keep the whole system going. What makes the dialectic symptomatic and 'indicative of repression' is the theme of the cunning of reason [which introduces some social dynamism again?]. The surrender of autonomy ['giving up jouissance'] will eventually lead to freedom, and this is the lure of slavery, both politically and psychologically. The slave can always split work and freedom [in his own practice as well?]. This cunning of reason is also found in an individual myth 'characteristic of obsessives, obsessive structures being known to be common among the intelligentsia' [with a baffling bit about professorial bad faith, which is limited in its reassurances by not guaranteeing jouissance, although there are some consolations in waiting for the death of Masters]. It is possible to externalize the whole game by adopting the locus of the Other [adopting research mode about oneself?] And this results in 'a "self-consciousness" for which death is but a joke' (687) [We also learn that most professors cope with ritualism, an 'educative banality': we seem to be learning rather a lot about French professors here]. The message seems to be that Freudian desire is behind everything. Professional psychology professors also are mostly concerned with 'obtaining a respectable position' and thus must reject a 'ludicrous' proposition that the unconscious has 'roots in language'. However, the mechanism by which needs turn into sometimes discordant demands still requires 'the defiles of the signifier'. The same might be said for biologistic accounts that insist that subsequent dependence and stress arise from the initial inability to move as an infant: this dependence is still 'maintained by universe of language'. Needs are diversified and operationalized through language and thus become subject to desire. That that has led to mistaken adverse moral and theological commentary about desire, even Sartre's position that desire is only a 'useless passion'. Instead, desire should be seen as having the 'most natural function' [presumably sexual]. It is affected by the 'accidents of the subject's history', especially contingent trauma, but there are also 'structural elements' operating despite these accidents. They can have an 'inharmonious, unexpected, and recalcitrant impact', and we see this in the flawed personal sexuality encountered by Freud. The real point of the Oedipus myth in Freud was not to explain sexual rivalry, but to ask an important question — 'What is a Father?' (688). Freud actually insisted that he meant '"the dead Father"', and this is what Lacan revives with his concept of the '"Name–of–the–Father"'. In actual societies, even 'among certain primitive peoples' it's never been possible to actually pin down patriarchal authority. Perhaps we will have to wait until widespread artificial insemination, especially of 'women who are at odds with phallicism'. The 'Oedipal show' certainly does depend on the society which has a sense of the tragic. [Typical asides!] We can start with the Other 'as the locus of the signifier'. There can be no other signifier [like God?] There can be no metalanguage of the Other. All laws are in effect justified on this basis. The Father is the original representative of the Law. Why should this be, when a more promising Other is obviously the Mother? It is because our own desires take shape through the Other's desire, [not our own for our mothers?] despite an initial problem of generating subjective needs. [entirely subjective before the discovery of the Other via the mirror stage?].It would depend on the relation between desire, demand, and need. When demand separates from need, desire 'begins to take shape' (689). Demand can become unconditional only if it is related to the Other. Demand is necessary because needs by themselves have 'no universal satisfaction (this is called "anxiety")'. The Other can, however, satisfy needs through 'whimsy'. This is what makes the Other look omnipotent, but it also introduces 'the necessity that the Other be bridled by the Law'. However, desire appears to be independent of the Law, indeed as the source of the Law. This happens because desire reverses the usual unconditional demand for love, which subjects us to the Other and becomes an 'absolute condition', detached from any normal social situation. This helps reduce the anxiety in a way that need cannot do. The effect was noted in psychoanalytic work on the transitional object. However, such an object is only an emblem, and causes desire only in accordance with 'the structure of fantasy' [or, indeed, of phantasy?]. When humans lack knowledge of their desire, it is not so much what they demand, but more of from where desire originates. This suggests that the unconscious is '(the) discourse about [of] the Other', and in French there is a stronger notion that 'of' implies 'objective determination'. But there is also subjective determination for grammarians, meaning that 'it is qua Other that man desires' (690), extending the scope of human passion. [Only in modern societies with subjects positively expected to be individualist and autonomous?] The Other is able to pose a question [as well as giving authoritative answers]. — "Che vuoi?," "What do you want?," [So why put it in Italian in the first place you knob — no doubt an allusion to an Italian writer]. Guided by psychoanalysis, subjects can come to see path of a desire, initially in the form '"What does he [the psychoanalyst] want from me?"Thus we come to graph three. [Note that the diamond-shaped is a Fregeian symbol meaning multiple combinations, 'designed to allow for 101 different readings' (691)]. This extra circuit explains the dilemma and misrecognition that a subject faces when he considers 'the question of his essence'. He might not be aware of this misrecognition, say when he develops a desire for what he does not actually want. It is common to attribute such desires to an ego that operates with intermittent desires. The same device also 'protects himself from his desire' (691).  [ d indicates desire, the lozenge is a symbol indicating multiple relations,apparently, in Frege's algebra]. This case shows that, often, self-consciousness is discovered only via 'another channel' this can include a structure of fantasy towards objects produced by 'a fading or eclipse of the subject', like the splitting that is experienced because of subordination to the signifier. The multiple connections between barred subject and other is what results. That term [top of graph 3] serves as an 'algorithm', an 'atom' of the signifying system is not to be read as a metalanguage, nor as something transcendent, despite informing all the analogous relations depicted elsewhere. Instead, we should see the other connections as 'indices of an absolute signification', which [apparently] will serve to cover even examples of fantasy [without literal or real objects or others?]. We see how desire adjusts to fantasy, the same way as the ego does with the body image, although the graph also illustrates different routes [one is apparently the inversion of the other]. Fantasy is 'really the "stuff of the I that is primally repressed, because it can be indicated only in the fading of enunciation' [pass -- because conventional enunciation cannot grasp it? Because of censorship?]. Nevertheless we are now in a position to see how the signifying chain takes part in the unconscious and in primal repression, so that it can take on the appearance of something subjective. We need to do this to explain cases where subjects cannot just be seen as things that utter statements, especially in cases where subjects do not even know they are speaking [in the classic psychoanalytic encounter]. This is why we needed the notion of a drive, 'pinpointing' the 'organic, oral, anal, and so on' elements that also explains such speech [but not in an adequate way?]. We are back to French terms [dunno why I just didn't just scan the diags in the book!] in this version of the complete graph, below, which adds a layer to the top of the graph with a cluster on the right to include Demand and its multiple relations with the barred Subject and the interaction of that node with the cluster on the left with S and the barred Other [signifier of lack in the Other, it seems] The drive is equivalent to [absolute human] demand without the subject, but it's necessary to include demand in order to distinguish the 'grammatical artifice' which separates out from the organic functions of the drive, and this would explain certain reversals of articulation between sources and objects discussed by Freud.  The emergence of distinct erogenous zones in drives is the result of another cut [development, further extension], based on some sort of analogy with anatomical margins or borders like the lips or the anus. This extends to erogenous objects like the faeces or the phallus '(as an imaginary object)' [the original boundary is the 'penile groove']. Lacan also wants to include 'the phoneme, the gaze, the voice… And the nothing)' (693). What links these objects is that they 'have no specular image' therefore no otherness, and it is this that makes them the very key to apparently self conscious subjectivity which claims the same. Again we see the phenomena in the claim that we can designate ourself as full subjects in a statement. [Very baffling here with an example that doesn't help about a writers block connected to the fantasy of producing a turd. Maybe it is that we think that the products of erogenous drives are uniquely subjective, perhaps because they are so private and secretive?]. These objects cannot be grasped in mirrors, but they are specular images nevertheless, just ones that seem to be produced by mysterious significant forces. The term on the top left, signifier of a lack in the Other, produces a kind of closing of signification, but from unconscious enunciation. [Because something has been subtracted from the limitless signifiers in the Other?] Nevertheless, it is the Other that still gives value to this sort of signification, [as in the bit earlier where the Other is asking those important questions]. The whole top section extends such significance to the interactions in the lower chain, 'in other words, in terms of the drive'.We can do no better in grasping this role, because 'there is no Other of the Other'. At least this helps psychoanalysts, who try to answer the question of what the Other wants from me, because there is no ultimate truth they have to maintain. The dead Father in the Freudian myth is situated in zone S of the barred Other, clearly a signifier of a lack in the Other. Usually, myths produce various rites, including psychoanalysis — which is not the Oedipal rite. This zone articulates something, is a signifier — and 'a signifier is what represents the subject to another signifier' (694). [It is possible here that 'signifier' refers to a source of signification rather than to a concrete element of a sign?]. All the other signifiers also represent the subject to this latter signifier [I am not at all sure why — only if the Other is being used in the construction of a consistent subject?]. There must be a signifier to which the subject is represented, or they represent nothing. [A further example of the necessary confirmatory role of the Other?]. The 'battery of signifiers'is complete in itself, requiring its representative function to be depicted by a line drawn from the circle. [Mystifyingly, and lying no doubt in Frege], 'This can be symbolised by the inheritance of a (-1) in the set of signifiers'. [Is this the same as the empty signifier in Barthes?] Apparently, this is in operation whenever a proper name is pronounced. [After some mysterious algebra], the subject misses something by thinking that he is 'exhaustively accounted for by his cogito — he is missing what is unthinkable about him'. [Really difficult here. A bit of set theory saying that a set cannot be known by any element it contains? — it seems to have something to do with subjects lacking proper names, possibly except when others award them?]. As a result, the [normal, or subject of the statement] subject cannot know where he comes from: he does not even know he is alive [referring back to the example of subjects not knowing they are dead until someone tells them]. How can he prove it to himself? What am I? We can at least prove to the Other that he exists, taking parallels with arguments about the existence of God, which were replaced only by the practice of loving him rather than logically demonstrating his presence. The only solution seems to involve Jouissance. Without such Jouissance, the universe would be in vain. This jouissance is accessible to me, I am responsible for it, but it is usually forbidden to me. This forbidding is not just a result of social repression, and nor can we blame some divine Other, which leaves only the I to blame (695), for example in the notion of original sin, which gets us back to the Oedipal myth again. By contrast, there is the castration complex, which serves as a 'mainspring' of subversion. Again Freud was the first to note this. It has rarely been properly explored in psychoanalysis, however, and has been replaced by a more Philistine general psychology. What it actually does is to constitute a gap in the subject, which is usually avoided in conventional thought. In this gap, 'logic is disconcerted' because the imaginary produces a disjunction in the symbolic. We should use this process to try to create an analytic method 'from a sort of calculus'. [Then a diversion into rejecting religious interpretations of the signifier of lack in the Other. Lévi-Strauss must also be rejected for seeing this residual religiosity as a zero symbol: it is the lack of this zero symbol that is more important. There is an obscure justification for using a particular symbol, the square root of -1, also written as i] Jouissance is forbidden to however speaks, prohibited by the Law. If it were lawful, we would get subjects obeying the lawful definition, which would not be jouissance. The Law bars the subject in order to bar access to jouissance. This takes the form of developing lawful and limiting pleasure, at least as far as not tolerating incest. This was not just Freud following tradition, because it helps solve a problem with the castration complex. Jouissance is symbolized by the phallus, and it is that that makes it potentially infinite. Prohibition must appear as a mark which requires a sacrifice. The phallus, 'the image of the penis' becomes negative as a specular image and that helps it represent the potentials and prohibitions of jouissance. This is an additional imaginary function, not the symbolism of sacrifice. Freud saw this imaginary function as producing a narcissistic stance towards objects. So the specular image shows the 'transfusion' of bodily libido towards objects [hence a bit I missed out above that the phallus gives body to jouissance]. However some parts of libido is preserved from immersion in objects, becoming autoeroticism [then a weird bit about the form it takes as 'a "pointy extremity"' which helps develop the fantasy of it 'falling off'. This also provides a separation from the specular image and is a 'prototype' for later conceptions of objects]. This is how the erectile organ symbolizes the place of jouissance, not as itself, not 'even as an image', but as something missing from the desired image. This is what he means by the symbol the square root of -1, as important in signification, and this is how jouissance itself becomes a missing signifier (-1). The real point seems to be to explain the reduction of the prohibition of jouissance to [prohibition of] autoeroticism. This is not just 'philosophical ascesis'. Nor was Freud advocating bodily regulation [of masturbation?]. This analysis does help explain the 'original character of the guilt generated by such practices' (697). Guilt arises from an awareness that jouissance generated by the proper use of the organ still has a remainder, and it is an example of the power of the signifier to prohibit objects. It is not just a matter of puritanical education or purifying traumas such as circumcision. The image of the phallic can be imaginary but become symbolic. Although it is based on something negative, and although it fills in some absent aspects, it does take on a positive aspect as well, 'the symbolic phallus that cannot be negativized' , the very signifier of jouissance. It is that that explains the differences of female sexuality, and the greater tendency of males toward perversion. Perversion arises when a particular object dominates fantasy, even more than routine sexuality [which is what jouissance seems to be implying here and above]. Object become substitutes for the barred Other. This produces the peculiarity that 'the subject here makes himself the instrument of the Other's jouissance'. [Then some difficult stuff about neurosis.] The gist of it is that's 'the Other's lack' is identified with 'the Other's demand' (698), so the others demand becomes an object for fantasy. The stress on demand explains the prevalence of frustration [of demand?] as a disguise for anxiety. Anxiety is really induced by the desire of the Other. This is easy to spot if the phobic object is sufficient to cover the whole of the desire of the Other. Other neuroses, however make it more difficult to recognize this link. Analysts have to suggest that there is a connection between fantasy and the desire of the Other. This provides two kinds of neurosis. First obsessives attempt to completely negate the desire of the Other, by developing a fantasy in which the subject cannot vanish completely. Second, hysterics sustained desire in their fantasies by attaching it to a lack of satisfaction. [Could be completely wrong]. The 'image of the ideal Father is a neurotic's fantasy'. We wish that the ideal Mother would tone down her desires [she is the real Other of demand]. But the Father is supposed to turn a blind eye to desires in order to fulfill his true function — 'fundamentally to unite (and not to oppose) a desire to the Law'. This is not always clear [!]. The neurotic wishes for the dead Father to become the master of desire. This has implications for transference and the neutrality of the analyst. Neutrality is more suitable in the case of hysteria, as long as neutrality does not frighten off the patient altogether, and as long as the patient is not suspicious of the role of the analyst's desire in neutrality. This offers an insight into the analyst's desire and how he must necessarily appear imperfect and not masterly. This is as important as the deliberate insistence on ignorance of each subject to comes for analysis, 'an ever renewed ignorance [the prat has the term 'nescience' before] so that no one is considered a typical case' (699). In fantasy, perverts can imagine they are the Other. Neurotics can imagine they are a pervert in order to control the Other [!]. This explains elements of perversion in neurosis. Both perverts and neurotics use desire [indirectly, attributing it to the Other?] as 'a defence against going beyond the limit in jouissance'. Fantasies can also contain 'the imaginary function of castration' although in a hidden and complex form. [Then a completely idiotic and obscure allusion to the relation between Alcibiades and Socrates].In the case of women, [which evidently has something to do with the allusion], the very absence of the penis makes her 'the phallus, the object of desire' [with a weird bit about how you can show the power of this absence by having women wear dildoes which will produce an arousing effect on men]. [Back to Alcibiades and Socrates, at greater length]. Apparently it all ends in an argument that the neurotic undergoes imaginary castration but this only sustains a strong ego: it follows that strengthening this ego in conventional psychology is completely misleading]. [After more obscure reasoning], castration is what regulates desire. We see this in fantasies where the barred subject and actual objects are joined together, in a way which becomes almost transcendental, guaranteeing the jouissance of the Other. This fantasy chain is then understood as the Other's Law [pass]. To come to terms with the Other requires us experiencing both the demand and the will of the Other. Then we have to realize ourselves as objects, or otherwise 'satisfy the will to castrate inscribed in the Other' (700). [Lacan claims to identify these themes in Greek tragedy or Christian despair]. This involves an initial refusal of [simple] jouissance in order to get to this more complex form [which might even include subordination to the Law?]. In an end note, Lacan says he added the stuff about Copernicus later on, as with the further consideration of castration. He wants to reply to a colleague who accused him of being a-human, and finds amusement in a Marxist critic possibly denouncing him as destined for hell. There are a couple of other in jokes as well, page 701. |