| Deleuze

for the Desperate #12 Faciality Plateau 7 of A Thousand Plateaus (ATP) on faciality offers all the classic problems associated with reading Deleuze and Guattari. It is a masterpiece of French elite academic style. There are all sorts of casual asides to novels by DH Lawrence and Henry Miller, work by Sartre and Lacan, American psychoanalysis, paintings and music, epics of mediaeval knighthood and recent work in embryology. Some examples just get a small paragraph, as a kind of passing thought, like the ones on bouncing balls in Kafka and a Nijinsky ballet, or discussion of the facial tic. This weird collection of examples is perhaps intended to show the universality and cultural significance of the faciality system, but only a philosopher could see any of this as evidence. There is a lot of repetition. Some sources are more explicit and adequately referenced, but not all. Some of the references are still in French of course. There are very abstract 'theorems' relating to general issues and horrible little scrappy diagrams. There is also philosophical thinking aloud kind that can look like evasiveness — maybe it is evasiveness. If you have lots of time and leisure, as I do at the moment, it is a treasure house, and I have much enjoyed tracking down some of the references and exploring them. However, if you are a hard-pressed student trying to get some basic argument out of this work, it must be deeply frustrating. These are the people I am addressing in this video. As usual, therefore, I'm going to stratify my offering. The video script will focus on the main points and just mention what I take to be the main issues, in so far as I can grasp them, but the transcript includes some extra comments to cover some more background. Let's get on with the main argument as I see it. We are told from the start that we are going to consider how two forces are going to be integrated together. We have already met these in the previous plateau (6) on the body without organs (BwO). The two forces are signifiance and subjectification. Signifiance relates to the ways in which what is seen as the proper construction of language controls us and what we can say. Subjectification describes the ways in which subjective identities are made available to us and also limit the potential of what we can do and think. You might remember that we saw these as two 'enemies' of the BwO. We have also mentioned faciality as a process which functions like the refrain We are told that D&G are going to operate as usual at two levels. Slightly unusually, we're going to discuss the abstract system first, whereas in the other plateaus it is often the other way around. First, there is the virtual or 'pure' level, dealing with an abstract system or machine of faciality. This will operate across a wide range of examples 'regardless of the content' (page 196). Second, there are some actual examples. The virtual system takes the form of an abstract machine, technically capable of producing the whole range of possible combinations of the forces involved. The concrete and actualized possibilities are produced by additional social and political forces, in the context in which we are operating. The actual examples largely turn on the role of the human face as usually understood, in social and political life, and in art. We are told that this is a really important discussion for understanding human culture, humanity itself, as well as the most general features of modern social life, none of which need resemble the conventional human face at all. This is because the virtual system itself is inhuman. We would expect this 'inhumanity' with any abstract or machinic system that operates at the level of impersonal universal forces, operating behind human cultural life. Understanding the faciality system in its full impersonality becomes important if we are to escape it, as we shall see -- we can develop new machinic possibilities altogether -- 'probe heads'. We are also told early on that the notion of becoming something other than conventionally human is going to be important, so there is a link with the discussion of becoming. At the virtual level, the basic components of machine faciality can be understood as a white screen and a black hole, combined in various ways. We are told in What is Philosophy (Deleuze & Guattari 1994) that Deleuze was intrigued by white screens from his interest in cinema, and saw white screens as an important component, upon which particular messages, sequences of language or symbols, are projected. The most literal and concrete example of the face is the one often seen in cinema or photography, the washed out, overexposed white face with contrasting black eyes. The notion of a screen can be used to refer to any surface upon which messages are projected, not just cinema screens (and this might be where the notion of a landscape fits in). Such messages are going to be treated as powerful forms of social conformity and control, which is argued strongly in other plateaus on language. The notion of a black hole comes from Guattari and his work on psychoanalysis (for example, Guattari 1995). The most concrete way to think of this is as a description of catatonic patients: all sorts of people attempt to direct communication at them, but nothing comes back, just as no information or light comes out of black hole in astronomy. The black hole appears in Guattari more generally to represent what we experienced normally as personal consciousness and personal passions, experienced as an inward dimension, a feeling that something is going on inside us, personal to us, something not necessarily socially shared. Ordinary subjectivity can degenerate into the more pathological catatonic kind when individuals obsess so much about their personal feelings that they develop black holes. We are talking about the sort of obsession with self that you occasionally find with great writers, or with those in the grip of consuming personal passions. One of Proust's characters — Swann — shows such an obsession as we shall see and there might be another example in the lovers' fatal passions in Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde . (I haven't seen it --try the Wikipedia account for a first step). Faciality in this opera even gets its own diagram on page 205. Components are always combined together. A sense of personal subjectivity is therefore integrated with social messages being projected onto various social surfaces and carried by ordinary language. Human subjectivity is never completely autonomous, but is always integrated with patterns of signifiance. In this way, social systems themselves provide for a number of positions, even though we think of those as our own forms of subjectivity. For me, this is the abiding political theme that runs throughout this Plateau, and it might be something to think about in particular for those of us in Anglo-US societies who tend to think that the individual person can escape, resist, even challenge social and linguistic arrangements by developing our own subjectivity and creativity. Modern French thinkers have always been far more pessimistic about this. For them, subjectivity does not spontaneously arise from individuals, but is itself constructed through processes that make us think we are autonomous, but which also require us to conform to existing social arrangements. I think that this pessimistic, or realistic if you prefer, notion of subjectivity can be found in most of the other plateaus as well. This obviously disagrees with those who see Deleuze (with or without Guattari) as an advocate of the sort of entirely subjective approaches to research that you see in developments such as Autoethnography: I have developed my own view in a recent open access publication (Harris, 2018) (free download!). Turning to the concrete examples, we find references to work in American psychology on the perception of the child, a topic which is discussed elsewhere quite a lot as well. Particular criticism is directed at Freud, but also at his disciples, like Klein. She has developed an argument to include the importance of things she calls 'part objects'('transitional objects' for Winnacott). These are important in the child's growing understanding of the external world. Objects like perceptions of the mother's breast or face are understood both as part of the integrated passional world of the infant, and, increasingly, as external real objects in their own right. Guattari in particular has frequently discussed the pros and cons of this particular approach, for example in Guattari (2014). Here, the approach is being criticized as claiming to be universal, as part of some inevitable stage of development. Deleuze and Guattari prefer a different model of development, one described as a matter of intensive forces arriving at different speeds in the development of children. We have a rather implicit reference here to background work on embryology, denying the existence of any fixed blueprint, and referring to how abstract biochemical forces and flows in the embryo territorialize or reterritorialize in different places and different times with subsequent effects on other flows. I think DeLanda's commentary is the clearest here (DeLanda, 2002). Freudian psychology, sees its own approach as 'science', though, and the actual words of the patient are always translated into the scientific terms. This takes place particularly in the dangerously authoritarian face–to–face context of conventional Freudian psychotherapeutic practice. This face-to-face system is represented as a 'four – eye machine', although that is not clear here. The term does explicitly refer to Anglo-American psychiatric practice in Guattari's The Machinic Unconscious (Guattari, 2011). We also find in Anti-Oedipus (Deleuze and Guattari 1984) freudian psychology referred to as an example of biunivocalization, a term discussed in a minute. I offer a brief summary of the critique of the Oedipus complex in a short paragraph on the transcript (below) Deleuze and Guattari use the term biunivocalization to refer to the colonizing tendencies of Freudian theory, especially in Anti-Oedipus. Freudian categories are simply applied to whatever it is that the patients happen to be discussing. As D and G say, for example, everything always turns on the Oedipus complex. In a famous case study, a young child, Little Hans, develops anxiety about going outside his house, even though he yearns to play in the street. Freud's early diagnosis is that this is the result of an Oedipal fear of his father's castrating power, based on some symbolic resemblance between his father and the horses moving up and down the street. In another case, one of Klein's patients, Little Richard, likes to draw maps of different European countries in different colours, and shows them being invaded by various naval forces: this is an Oedipal anxiety about adult sexuality and the bodily invasions that it implies, says Klein. There is quite a good early article on these cases in Deleuze (2006). The point is that whatever they say, no matter how personal or idiosyncratic it might be, utterances of the patients all turn on Oedipus. Their cure depends on them accepting this diagnosis. When patients finally agree, one voice fits the other so smoothly that there is a single regime of understanding. We have here the pessimistic account of subjectivity as never free but tied to a set of fixed positions provided by a system, a theoretical one in this case.

The text then provides us with a casual and unreferenced aside about the work of Sartre and Lacan, and how the discussion of faciality helps ground their work and logically precedes it. They use terms like 'the look' and 'the mirror phase' respectively, and this is where online aside 1 spells out some of the implications. We then encounter various theorems relating to deterritorialization. That concept is, of course, important to other discussions in ATP, including ones about lines of flight, which is where we encountered it in this series of videos. These theorems extend the formal qualities of deterritorialization. To give you just the gist of the argument as I understand it, we need this extended discussion to avoid oversimple interpretations of the term. Deterritorialization is a complex matter, where elements can be linked with other elements in whole systems or structures. Each element has a different potential for deterritorialization, so various possibilities of contamination or escalation exist, as the deterritorialization of one element affects the others. Faciality shows all the complexities of deterritorialization. Initially, it is quite a simple matter, where the human face gets deterritorialized from its original setting, the human head. Then a particular historical process ensues which produces further deterritorialization and further relations with other elements, as we shall see in the case of cultural activities. The face actually offers an absolute deterritorialization (page 191), represented as the highly abstract system of white screens and black holes. The system will go on to dominate large areas of culture as they reterritorialize on it. This is why we should understand the face quite distinctly from the ways of understanding bodies: faces are coded differently. This extensive power of deterritorialization and the potential for reterritorialization of neighbouring components explains its cultural role. The face can now overcode a wide range of cultural activity, offering a very general and widely applicable coding system. We have to remember that we are not just looking for simple resemblances between faces and other cultural elements, but rather for the same machinic operations. Incidentally, the underlying system can also be understood as a surface with holes, or a holey surface, and this is discussed briefly right at the end of the Plateau on smooth space. How did this system develop? It is not essentially human, but draws on inhuman forces. It is not just that faces appear as inhuman in certain circumstances, in very large close-up, for example. The faciality system is not the result of an evolution or a necessary stage of development. It has nothing to do with psychoanalytic stages of the development of human subjects. It does not involve ideology in the usual sense (as deliberate strategic communication) , but is more an abstract issue of 'economy and the organization of power': it is a very powerful and flexible way to overcode human life. Social power has not always been exercised through faciality. In 'primitive societies' (page 195), there is a different semiotic, something 'essentially collective, polyvocal and corporeal', expressed in a variety of forms and substances, but usually involving bodies and the domination of them. Speech, symbolism and ritual act as forms of bodily domination. These can achieve some limited becomings, usually becomings–animal, invoking animal spirits of various kinds, for example, but more abstract ones are needed in modern societies. Faciality actually emerges with the power of White Man, with European dominance, symbolized by the face of Christ spreading everywhere and becoming the model of the seemingly universal human face (which is what I understand by the Latin tag facies totius universi on page 196). Here, the system of power works in a new way, focused on the key process of biunivocalization. To simplify, univocalization occurs when a single speaker voices a statement that reflects their own understandings and beliefs. Bivocalization clearly involves two people speaking and making statements. However, biunivocalization describes a situation where two voices may be speaking, but they are both offering complementary versions of the same statement, the statement offered by the dominant speaker. Different speakers might take turns to make versions of a statement, but that statement will still reflect the interests of one speaker. An oppressive ruler might be making a statement about something, and we might find ordinary citizens offering the same views, apparently quite spontaneously and independently. Or we might have some sort of call and response system, where a powerful speaker makes a statement about something and then asks for responses, and the listeners give personal examples that illustrate and fully agree with the view. We will add another example in a minute The faciality system is biunivocal. Whatever the variations in content, centres and surfaces provide a coherent basic unit with the same underlying logic — to express subjective meaning in conventional language you need a twofold combination of surface and subjective centre. Not only that, the subjective centre itself also operates only with binaries, usually of a simple '"yes – no" type'. And there is a further form of biunivocalization to add to the examples above. Any system that is going to domesticate a complex society cannot be too rigid, and has to deal with new cases that emerge now and then. The faciality system works to domesticate anything that might be emerging as a challenge — 'the white wall is always expanding, and the black hole functions repeatedly' (page 197). For example, if the traditional binary difference between conventional men and conventional women comes under strain, new categories can be invented — the example is the category of transvestite in the 1970s (many more categories exist in 2018). This category will not necessarily be particularly hostile, but it will be part of the abstract machine, not something outside that can challenge it --so what do you think about the politics of the growing list of categories as in LGBT -- QA etc? At this point, there's quite an interesting discussion about 'European racism'. We have already seen that faciality is based on the emergence of White Man, so nonwhite people, when they finally appear in the heartlands of Europe for example, have to be categorized as deviants in the way suggested just now. I thought at this point of some British work on black people and how they finally began to appear on British television, first of all as barbaric savages or criminals, then increasingly as slightly more tolerant stereotypes such as 'noble savage', talented natural athlete or musician. Of course these are all still sometimes used in social discrimination. Deleuze and Guattari argue that none of these categories actually grasp very much about otherness — 'Racism never detects the particles of the other' (page 197). Black people are granted otherness but on the terms of the system and there is no recognition of any other kind outside the system. There is parallel work in feminism to draw upon here as well, not mentioned in Deleuze and Guattari though. Irigaray (1985) suggests that in patriarchy women have a limited identity just as 'not–men', not even as proper others. Going back to the text, we can conclude that language and signifiance squeeze out any heterogeneity and offer continuous translation of it back into an overarching system of categories. Again I thought of early work on British television which had to manage a range of political opinions, including anything that lay outside the usual Parliamentary consensus. Representatives of conventional Parliamentary parties were offered places on a panel in the studio on the left or on the right of the neutral chairperson (a BBC presenter) in the middle,but anyone outside that consensus,like radical trade unionists for example, were interviewed literally outside the studio, often on the street or against some standard background like a picket line or a crowd. The last time I saw that sort of display was during a BBC discussion of the impending referendum on Scottish independence in 2014. All sorts of conventional spokespeople were gathered in a cosy tent but the sole working-class dissenter (advocating remaining in the union with England) was interviewed outside in the cold drizzle. We learn that 'language is always embedded in the faces that announce its statements' (page 199) and you might need to remember this argument if you encounter elsewhere, such as in Plateau 4, apparently strange statements like there is no such thing as language in its own right. No separate language also means no separate level of subjectivity either, no subjective choices as a prior activity which then expresses itself in language — subjectivity is not outside of language. Subjective choice presupposes the faciality system and how it has already constructed with binary signifiers and binary subjective identities. In this sense, 'it is faces that choose their subjects' (page 199), not the other way around. That is, the faciality system has constructed human subjects in the first place. Again we are reminded that linguistic operations and the operations of subjectivity do not look like the same kind of thing, and neither resemble a human face, but nevertheless both arise from the abstract operation of faciality. As a result, they are always found combined together.

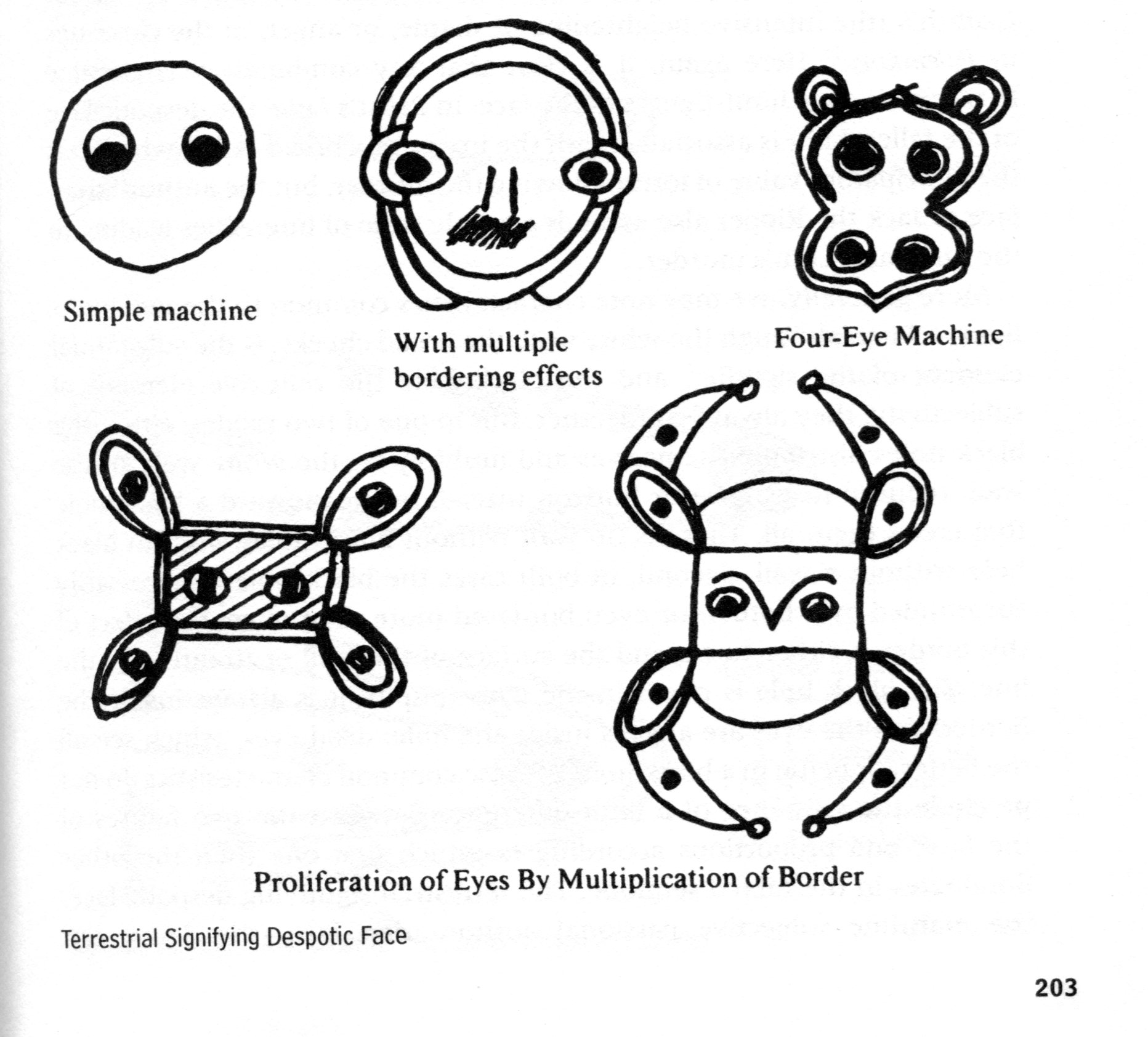

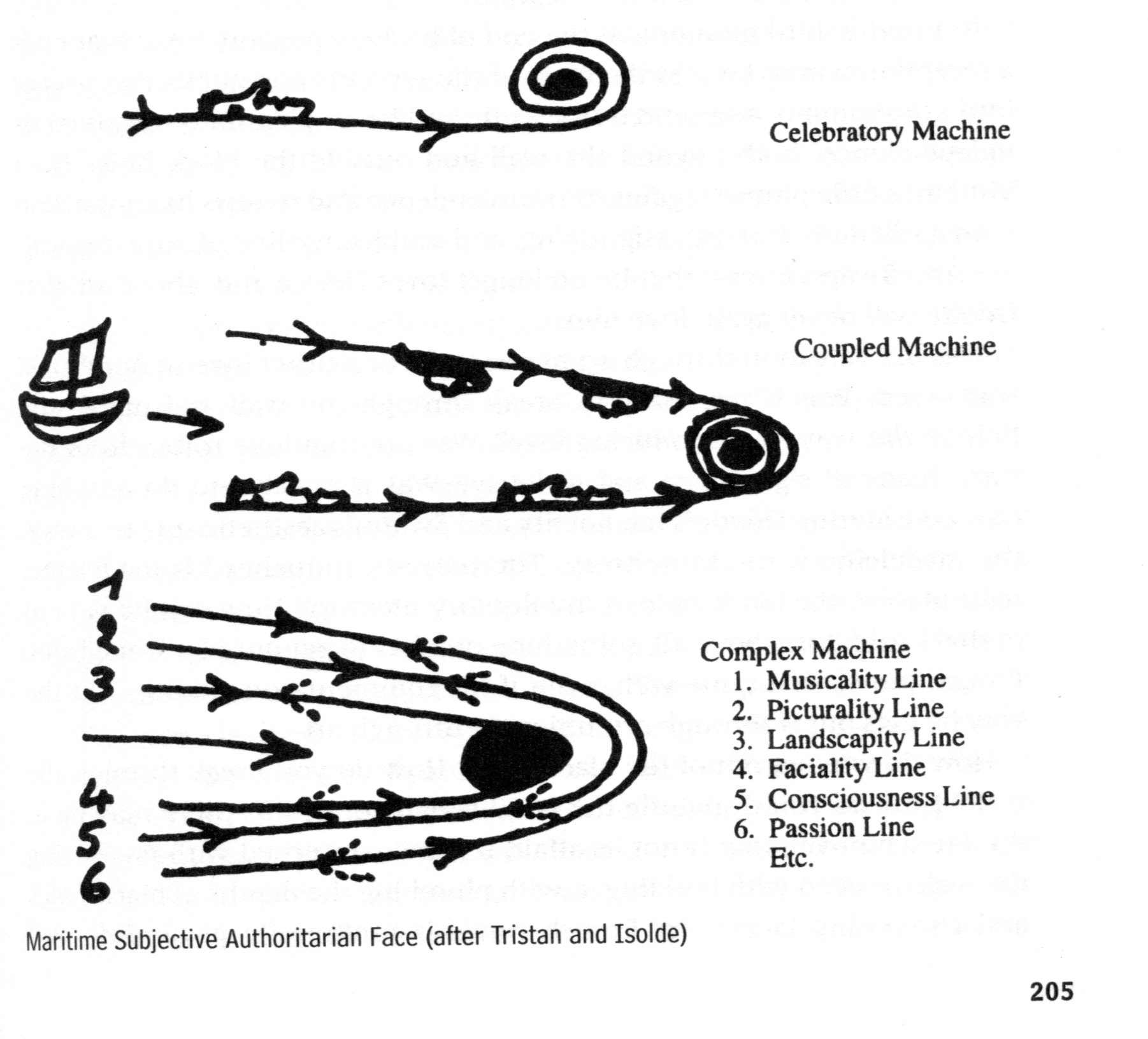

So certain social formations need faciality systems, and also landscapes, we are assured, although I still do not see quite how landscapes fit in (I've had a go in aside 2) . Our social formation has colonized the earlier systems of power which were much more polyvocal and far less individualized. We now have a fully modern process of signifiance and subjectification which tries to deal with all eventualities. This explains why the modern body is so heavily disciplined, because bodies were once the source of alternative corporeal forms of semiotic. Colonization took place, and is maintained, precisely because modern systems of signifiance and subjectification are so abstract, so deterritorialized, and are thus generally applicable. Social change has deterritorialized the older systems, but instead of developing new territorialized relations of their own, they have been colonized by highly deterritorialized systems, one of those outcomes predicted in the theorems of deterritorialization. In detail, there are specific assemblages of power at work, and these form two main kinds — despotic and authoritarian. Both are involved in crushing otherness and heterogeneity. There is much discussion of various power assemblages in Anti-Oedipus. Roughly, a despotic system is based around the presence of a single ruler, leader or institution which monopolizes all power and acts everywhere. An authoritarian system is more like our own; depersonalized, based on institutions that make us conform willingly, such as systems of contract. Sometimes the two forms are mixed. There are some additional possibilities as well, some of which are illustrated in the curious diagrams on page 203.  There might be moving black holes for example, or more than two. We can add circles to add diagrams to show how the black hole can expand its areas of operation: inside each new black hole is an eye in some of these examples, some of which are drawn from Mercier's book on Ethiopian magic scrolls. Have a look at aside 3 on that book if you wish. Black holes can overlap, 'enter into redundancy' (page 202), and this is how despotic systems work to proliferate the centre of power and spread it across the whole surface. In another case, perhaps describing the modern authoritarian regime, the wall of the signifier becomes something that looks rather more like a line. We are not actually told much more about what this represents, but perhaps it is a personalized version of the signifier? We see these lines in the diagrams on page 205.  In some cases, it seems, the

line bearing signifiers heads toward one

dominant black hole. Sometimes, opposing faces

will appear, representing either two persons

or aspects of the same person, say their

rational consciousness and their subjective

passions. In the third example, it seems as if

various kinds of artistic representation can

be made to converge, perhaps on one decisive

act, like the final scenes of Tristan und

Isolde, where more or less everyone dies

passionately. I am not at all clear why this

is called a 'maritime' case, but it might

refer to an argument by DH Lawrence's essay on

Melville (Lawrence, nd): note 18, page 590,

says the essay 'begins with a lovely

distinction between terrestrial and

maritime eyes'

I've read this, but can't see what they mean. This is the beginning:

Then we get to a major example, Proust who was 'able to make the face, landscape, painting, music, resonate together' (page 205). I have my own summary of the novel on my website. In this example, we are reminded how Swann persuades himself that Odette is a beautiful person, worthy of his love, despite being of humble origins and having a dubious reputation as a courtesan. He does this by looking at parts of her face and seeing in them reminders of parts of faces in classical paintings. Specifically, according to my notes on the novel, she recalls a Giotto painting of Zipporah in the Sistine Chapel:  I understand the Google Arts and Culture app now helps you do something similar, by locating your own selfie in a classical painting. Back to Proust, the same music always seems to be playing when Swann meets Odette in various salons, and he begins to add value to the meetings, to use a phrase found in leisure studies, by associating them with a particularly beautiful musical phrase. However, all these aesthetic efforts push Swann into a crippling obsession with Odette and he follows all these efforts 'along a line hurtling towards a single black hole, that of Swann's Passion'. He is eventually able to escape and put things back into perspective only by considerable intellectual reflection on music, separating its effects from subjective people and subjective feelings, attaining a kind of 'salvation through art'. That is, he finally gets a proper technical understanding of art in its own right, seeing that it does not just express subjectivity, but has its own internal rules of composition which offer many more possible meanings. Generally though, French novels are not very good at helping us get out of black holes we are told. This massive generalization is followed by another one praising Anglo-American novels which stress the theme of escape, breaking out of social constraints, travelling and having adventures. However, there is also an awareness that escape is going to be very difficult as we shall see. The same goes with breaking from conventional signifiance, and even Christ was unable to break entirely with conventional understandings — 'he bounced off the wall' is the way they put it, page 207. The trouble is that our culture exerts a massive inertia over any attempt to escape. This means there are some risks in doing things like becoming animal or becoming imperceptible, which leads to warnings at the end of the Plateau. We will need to draw upon all the resources of art to resist and escape, especially 'art of the highest kind' (page 208), which probably implies art that engages with philosophy. In experimental writing you can become animal or become imperceptible, and the same goes with music. We have to be careful that we do not see art as a refuge, however, and allow it to reterritorialize us too early. We have to go all the way instead 'towards the realms of the a–signifying, a–subjective and faceless'. This is risky, and 'madness is a definite danger'. Clinical schizophrenia could be seen as a form of total loss of the sense of face, for example. Incidentally, there is also a bizarre discussion of the facial tic, which I will leave you to read to enjoy, page 208. Breaking out of faciality will always be a political act, something real, with real consequences. One possibility is 'becoming–clandestine', which perhaps here means avoiding the usual categories, not willingly conforming but keeping something back, so that you are no longer open to total control. As usual, though, it is necessary to do some philosophy first, some extensive analysis to 'find your black holes and white walls' so that they might be dismantled, or that we might find lines of flight. We should not be tempted to think of simply returning to become a primitive person again. This will not leave behind the categories that we still think with: when we look at 'the deep ocean, we will think of the lake in the Bois de Boulogne' is how they put it (page 209). Or we will find ourselves reterritorialized again. For these reasons, a return to some precapitalist arrangement is 'an "impossible return"' (quoting DH Lawrence's critique of Melville's novel of living amidst noble savagery Typee). We should not return, but rather move forward to think of new ways of living — 'we can't turn back'. Instead, we have to find new uses for the walls and black holes we have been given. We need to analyze signifiance in order to try to develop 'lines of a-signifiance'. We should escape from memory that constrains us, try to avoid previous interpretations, and examine our own subjectivity to try and find those 'particles' that have not been domesticated. In our relations with others we need a kind of transformed love which is nonsubjective, which does not attempt to colonize the other, but explores others as genuinely unknown. We can do the same with landscape traits and with other forms of expression like painting and music. Giotto's painting of St Francis shows that there are possibilities in depicting religiosity, even working within the conventional codes of Catholic Christianity. DH Lawrence, despite his pessimism, admits that conventional travellers can at least become lost, '"mindless and memoryless beside the sea"' (page 210). This is a quote from Lawrence's Kangaroo and refers to the culture and eco shock experienced by a Brit bourgeois on living for a while in Australia.The Brit also yearns for some wonderful new and rather fascist form of government based on manly love, naturally with little thought given to any intermediate institutions. Deleuze's admiration for DH Lawrence runs throughout the book and is hard to explain,but, apparently, his long-suffering wife Fanny was engaged in translating Lawrence, so we might be overhearing some pillow talk chez Deleuze? In summary, the abstract machine of faciality links us to definite political and social strata in a way which offers only a limited freedom (a limited form of personal deterritorialization) or tolerated forms of harmless deviancy. This system colonizes and extends itself consistently (it develops 'on a plane of consistency' is the way they put it, becoming a diagram). However, there is one liberating possibility — faciality can produce a 'probe head', something that searches or guides, that breaks through strata, pierces walls, and escapes holes of subjectivity. Deterritorializations can become more positive and creative. Lines and holes need not form a unified system, nor extend to fully colonize landscapes, paintings or music. Faciality traits can be freed to go off and develop rhizomes of their own, linking up with previously unknown aspects of landscapes, painting or music. Overall, current notions of the face (of subjectivity or personhood) are 'a horror', necessarily inhuman (in the pejorative sense as well?), produced by a machine to serve the interests of apparatuses of power. Even 'primitive' forms are inhuman too although they combine forces differently, with 'very different natures and speeds' (I think we have discussed the notion of speed before, which refers both to when a force arrives to be combined with others, and the extent to which it can combine across a range of other forces -- high speed means the capacity to connect with a wide range of other forces and thus induce qualitative change from an accumulation of impulses). We should try to develop a more liberating inhumanity — the probe head, something which explores, something which seeks out deterritorialization and lines of flight, intending to form new becomings and polyvocalities. Our slogan might be 'become clandestine, make rhizomes everywhere' (page 211). But even so, this still looks a bit unsatisfactory — 'must we leave it at that, three states and no more: primitive heads, Christ face, and probe heads?'. I think this unsatisfactory nature of analysis of the faciality system might explain its near absence anywhere else in subsequent work. I cannot remember offhand a single reference to faciality in Deleuze's massive two volume discussion of the cinema which we reviewed in other videos (Deleuze 1989, 1992). Guattari's work on subjectivity does mention it occasionally and there is a short essay on faciality at the end of his book Schizoanalytic Cartographies (2013). Here, there is a review of some portrait photographs at an exhibition by Eiichi Tahara, which repeats some of the themes of this Plateau but also jousts with Barthes on the aesthetics of the portrait photograph. The main point developed is that further deterritorialization of aspects of the face , selected by blanking out or masking the remaining sections, for example, permits those aspects to be used for artistic purposes beyond conventional representation. References Delanda, M. (2002) Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy, London: Continuum (my notes here) Deleuze, G. (2006) Two Regimes of Madness: texts and interviews 1975--95. Ed D Lapoujade. Trans. Ames Hodges & Mike Taormina. New York: Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents Series (notes here) Deleuze G and F Guattari (1994) What

is Philosophy?, London: Verso Books.

(notes here) Deleuze, G (1989) Cinema 2 -- the time-image, London The Athlone Press. (notes here) Deleuze G and Guattari F

(1984) Anti-Oedipus. Capitalism

and Schizophrenia, London: The Athlone

Press. (brief notes here) Guattari, F. (2015) [1972] Psychoanalysis and Transversality. Texts and interviews 1955-1971. Introduction by Deleuze. Translated by Ames Hodges. South Pasadena: Semiotext(e) (notes here) Guattari, F. (2014) The Three

Ecologies (I.Pindar and P Sutton,

Trans.) London: Bloomsbury. [Also has

an essay by Genosko on the life of Guattari,

focusing on transversality] (notes) Guattari,

F. ( 2013) Schizoanalytic

Cartogrphies. Translated by

Andrew Goffey. London: Bloomsbury

Academic. (notes) Guattari, F. (2011) The Machinic Unconscious. Essays in Schizoanalysis, translated by Taylor Adkins. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents. (notes) Guattari, F. ( 1995) Chaosmosis: an ethico-aesthetic paradigm. Trans. Paul Baines and Julian Pefanis.Power Publications: Sydney. (notes) Harris, D. (2018)

'Subjectivity in autoethngraphic

collaborative writing: a deleuzian

critique', in International Journal of

Sociology of Education 7 (1): 24--48.

DOI 10.17583/rise.2018.2881 Irigaray,

L. (1985). This Sex Which is Not One.

Trans C.Porter and C. Burke. New York:

Cornell University Press. Lawrence, D

H (nd) Herman Melville's Typee

and Omoo. In Studies

in Classic American Literature,

Chapter 11. Online https://biblio.wiki/wiki/Studies_in_Classic_American_Literature/Chapter_11 Martinot, S. (nd) The Sartrean Account of the Look as a Theory of Dialogue. Online https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~marto/dialogue.htm Wikipedia (nd) Tristan und Isolde. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tristan_und_Isolde |