Resources on the 'Marjon Moment'

Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth

[Notes from Dictionary of National Biography.Volume X for Kay - Shuttleworth (1804 -- 77). James Kay added the name of his spouse, Janet Shuttleworth on their marriage. He began life as a medical man, working particularly with the poor, and was horrified by the cholera epidemic of 1832, which led him to press for reform of insanitary conditions. In 1835, he became an Assistant Poor Law Commissioner. He joined the Privy Council Committee to administer the grant for public education and soon became First Secretary. He resigned from the Committee in 1849, and was created a baronet. He established Battersea College with his own funds and those of a colleague and acted as principal 1839 - 40. On his resignation from the committee, he devoted his life to writing pamphlets, and serving good causes such as the Relief Committee for the Lancashire cotton famine (1861 - 5).]

Stewart, W and McCann, W (1967) The Educational Innovators, London: Macmillan and Company.

Chapter 11 -- Kay - Shuttleworth. K-S is recognised as a founding father of British education. He was especially interested in Continental reformers and introduced the work of Pestalozzi into elementary schools in England.

He began his career as a medical man, and then as an Assistant Commissioner of the Poor Law Board, and saw the need for education for poor children, partly to protect their health. He had a rather fond if patriarchal approach to working class children, and saw himself as promoting self-improvement for pauper children. He opposed universal education, though. He took care to emphasise his support for the traditional remedies too --'steady and persevering labour' and 'instruction by religion'. He looked for appropriate methods to educate poor children, especially in Scotland and Holland. Among his other posts, he was Secretary of the Committee of the Council of Education, a body which oversaw the first beginnings of state education in Britain ( by advising on the spending of whatever grant for public education Parliament agreed). Kay-Shuttleworth also appointed the first inspectors.

He was an advocate of the pupil - teacher system, which was also inspired by Pestalozzi. As with all reformers, he had to bear in mind a number of other factors: the level of resources in particular. However he thought that the pupil teacher system was superior to monitorial methods: it also permitted 'natural learning' rather than rote learning. His belief was justified following strong criticisms of the monitorial system in the late 1830s -- these included widespread bribery and corruption among the monitors, and little signs of real educational progress. His own inspectors confirmed this view.

He saw the Pestalozzi method as involving moving from: 'the known to the unknown, by gradual steps', and argued that this must be led by a teacher of proper skill and education. Clearly, new groups of teachers were required, which led to the establishment of the first teacher training colleges. Kay-Shuttleworth had originally founded his own teacher training college (religious rivalries had prevented State support) after a trip to Europe. He had especially liked German schools with their emphasis on 'educating the heart and feelings as well as cultivating the intellect' (page 183).

From 1839 --40 he ran the Battersea College, from his own funds, and those of a colleague, for apprentice teachers (from Normal Schools) and for others intending to enter the semi-profession. Pestalozzi's methods were to be disseminated: teachers were advised to move from the simple to the complex, to prioritise actual examples rather than rules, and to use natural objects and illustrations rather than books. Reading was to be taught via phonics, and English was to be taught orally rather than from the conventional grammar book. There were also signs of a 'vocational' curriculum -- students studied book-keeping, elementary mechanics, drawing, design, and geography -- these were seen as relevant for trade and the economy. Kay-Shuttleworth also had a lifetime interest in a curious method of teaching music vocally, as we shall see -- the Hullah method: music would create a 'diffuse joy and honest pride over English history' (cited in Stewart and McCann page 185). Kay-Shuttleworth found trainee teachers as among the most demoralised groups. He improved things by trying to keep College life austere, semi monastic -- his critics said it was too puritanical.

His college eventually failed -- the Church of England became very suspicious again. As a result, government funding dried up, and the college was handed over to the National Society -- it became St John's College, Battersea.

Kay-Shuttleworth went on to publish textbooks containing his views on teaching. He was particularly interested in curricular reforms especially using the 'constructive method' [ which seems to have involved contructing larger concepts from simple elements]. He offered a regime based on reason and affection. His reliance on phonics can be seen as an example of his rational approach -- the teacher analyses speech into phonemes, and then structures the curriculum to teach them, singly at first and then in combinations. Writing and drawing were similarly broken down into their simplest components first, so they could be more rationally taught. Drawing could be justified as a route to self-improvement, Kay-Shuttleworth felt: it offered both a commercial skill and it raised the taste of the poor. Stewart and McCann see these proposals as a further over-simplification of Pestalozzi's views, and some Pestalozzians disagreed with them, but the main use was to serve to oppose the monitorial method.

As well as producing teaching manuals and pamphlets, Kay-Shuttleworth championed the Hullah method of teaching music. This involved communal singing, accompanied by certain gestures of the hands which represented the notes and intervals in music. Singing was designed as an early form of 'rational recreation' -- it promoted contentment, developed natural strength and energy, and fostered the diffuse sentiments mentioned above. It also added to the knowledge and prosperity of the country. Singing was taught at a series of public lectures originally based at the Exeter Hall in London [an early form of distance education!]. Fees were charged at different levels according to income. For a while these lessons were very popular with working class groups, and they also seemed to offer a neutral ground upon which religious rivals could agree.

However, they were soon attacked by the radical press. One problem was the special notation used in the lessons (apparently it was the 'tonic Sol fa' notation), and the hand movements were ridiculed. This kind of musical education was seen as too abstract, and there was annoyance at State support for it, especially when it threatened to monopolise the teaching of music. A familiar argument was advanced as well -- music education seem to be at odds with the way the rest of the syllabus was taught. In particular, of course, it was insufficiently religious for the National Society. Financial difficulties finally brought an end to the scheme.

Overall, Stewart and McCann describe Kay-Shuttleworth as an administrator rather than a theorist, as a pragmatist not a revolutionary. His ideas in education were finally undone by the Revised Code of 1862 -- advocating the method of 'payment by results' -- and the change of climate it signalled.

Kay-Shuttleworth wrote a Memorandum on Popular Education, [republished in 1969 by the Woburn Press, London and stored in the Marjon archive], and makes points similar to those of Coleridge (see below). The Revised Code will produce only minimal effects, and Kay-Shuttleworth cites some convincing and comprehensive statistical data to both deny that standards were falling before the Code, and that standards have risen since. He uses these data to argue for the superiority of the pupil-teacher system, comparing it favourably to the monitorial system. Finally he asked for some consideration of the views of the student population to be taken into account.

Derwent Coleridge

[Notes from Dictionary of National Biography Volume IV for Coleridge (1800 -- 83). He was determined to be his father's disciple in matters of religion [and education]. He became the Principal of St Mark's College in 1841 and lasted until 1864. He was an accomplished linguist, speaking, among others Arabic, Coptic, Zulu, and Hawaiian. His introduction of choral services was regarded as a particular novelty. After leaving St Mark's, he returned to the Church as a Rector. He finally retired to Torquay]. There is a full-ish memoir of him written by fans -- Hainton R and Hainton G (1996) The Unknown Coleridge, London: Janus Press, which contains useful material on his Principalship at St Mark's

Several documents written by Coleridge survive in the Marjon archive I acquired them with the marvellous assistance of Ms A Bidgood, the College Archivist:

Coleridge, D (undated -- 1843/4? -- the Haintons think 1842) A Second Letter on the National Society's Training Institution for Schoolmasters, St Mark's College, Chelsea, addressed to the Venerable Archdeacon Sinclair, Treasurer of the Society (unpublished, in Marjon archive).

This letter is a general report on the state of the College. It begins with noting the number of students recruited since 1841 -- ninety seven, including three Syrians! At the time of this letter [which must have been one, two or three years later] 81 students were left and 16 had withdrawn for various reasons, often for health reason. Coleridge reports no problem with the payment of fees, which was an early worry, and even suggested a modest increase. He includes some details of 'first destinations' -- most went to be schoolmasters, some to be clergymen, some took posts at the College.

On Students

'A fair proportion are intelligent lads... but... few are properly prepared'. However even unprepared students could not be excluded at the risk of threatening the viability of the institution! They 'cannot read well... nor write correctly from dictation'-- a result of bad teaching -- and were 'quite ignorant of grammar'. They had an insufficient vocabulary to benefit from 'oral teaching... much less to gain information for themselves from books' (page 3). There was a need to go over again the work of the elementary school. Coleridge was reluctant to recommend lower admission requirements, and hoped instead to forge stronger links with the dioceses, who might sponsor suitable candidates, and help seek out more promising youths. However a wider recruitment base would require more accommodation to be built at the College.

The health problems arose

because

candidates for such a profession tended to be from the 'least

vigorous

of... children'. Some were 'weaklings', prone to 'glandular

derangement', or 'rheumatic affections' [sic]. Coleridge was

worried

about whether they would be able to cope with the 'confinement

and

drudgery of the teacher's office' (page 7). Again, there was a need to

tolerate some medical problems, or most of the applicants would have to

be excluded. Coleridge claimed the college was able to achieve a marked

improvement in health, without loss of study time, thanks to matters

like

diligence, and 'early rising' (page 7). Students were also

offered

a 'variety of occupations, mental and bodily', including

'industrial

employment... in the open-air', and periods of 'united devotion',

which was calming and beneficial. There was also a 'judicious and

moderate use of gymnastic exercise'. Teachers must be fit for work in

noisy

and unventilated conditions, and they needed self-discipline to

overcome

the considerable anxiety of their calling. They needed commitment

especially

as a good teacher would be constantly vigilant, supervising the

'deportment

and the moral well-being' of their charges, and often offering extra

tuition

out of hours: indeed the most zealous teachers were especially likely

to

be challenged, especially when they were very likely to encounter in

their

charges 'falsehood and dishonesty... sullenness and insolence...

the evidences of an evil nature and the early development of vice'

(page

8). However, Coleridge was aware that some teachers would be

tempted

to cope by going through the motions -- 'The duties of a

schoolmaster

may be evaded to an indefinite extent' (page 9) -- [although he wanted

to prevent that sort of 'coping strategy'].

Pupil-teachers needed to develop a self regulation of effort to economise in their exertions. They had to manage classrooms, including important aspects like arranging proper ventilation [a favourite theme of Coleridge's], and temperature. They had to take exercise, control their anger, protect against anxiety -- and here it helped to depend on 'Divine support' (page 9). Teachers also deserved adequate pay and holidays, particularly to avoid the need for unhelpful 'extra employment' [ he was not against useful work in the community like assisting the clergy, or helping farmers to measure and assay their land].

The Staff

The College employed three Masters on salaries of about £100 a year. Even though they were offered free accommodation and some meals as well, this was regarded as inadequate. However, Coleridge was able to offer new recruits some perks -- for example that they might use their time at the College as preparation for the clergy. Masters taught about 24 students per class. The entry qualifications of students were so varied that individual tuition was expected too. Coleridge took a broad view of college lecturing -- apart from teaching them, students also needed to be 'watched and warned, corrected, encouraged, advised' -- so there was no room for staff cuts at present (page 12). It was also especially important at a College to recruit a suitable [collegiate] body of teachers. Masters were given individual responsibilities as well as their teaching duties: one was especially responsible for the practice school (the 'normal master'); there was also an 'industrial master', who maintained order and discipline and set an example (the benefits of labour were to be seen 'as a blessing'). The college used monitors too, but they were heavily supervised to avoid 'presumption as regards their superiors... [and an]... overbearing manner towards their charges' (page 12. There was also a steward/book-keeper and a master for the second practice school.

Teaching at the College

Coleridge went on to describe, then justify the syllabus at the College.

The aim of the college was to impart 'a sense of duty' into trainee teachers. It tried to exert an influence over its students --'Mental cultivation... [is]... extremely favourable to moral improvement' (page 19). Ignorance would lead to superstition, for example, but no amount of instruction could produce such a relapse.{ I wonder what he would of made of the 'postmodernist crisis', where learned academics ended a career of detailed study with a lapse into relativism?]

Coleridge did not agree with those who said that the poor needed no education, that education would make them unhappy, that they were better off undisturbed by 'enlightenment', or that they should be taught by 'dogmatic instruction' only. He was in favour instead of the 'free circulation of knowledge', aiming to inspire the poor with hope, to raise them 'to a sense of their own dignity... [but only]...to reconcile them to their lot in life', to enlighten. Partly this was to overcome the effects of ignorance which has 'ever furnished political agitators with too powerful an aid' (page 20). Finally, for him, faith was a condition of knowledge, which opposed attempts to split secular knowledge and religious knowledge [which were threatening the Church's hold on education].

Teachers needed higher education. They needed to acquire mental discipline, both moral and intellectual. Coleridge was more worried about not hitting these high standards, especially as he was aware that what is learnt is not necessarily what is taught (page 20). The average standard of his students was low, but he was unwilling to sacrifice the most promising ones by lowering standards overall. In any case he hoped that the faults could be remedied by good teaching.

NB the 'Elliptical

method'

seems to involve the strategic use of the 'ellipsis' ( an omission in

the

text, often indicated by the symbol of three dots (like this ...).

Presumably,

the teacher would miss out words from his peroration, and ask

individual

students to supply them to see if they had learned their lesson -- as

in

the 'cloze procedures' of today. The 'Simultaneous Method' seems to

have

involved getting the whole class to answer at once --perhaps as in the

famed chanting of the multiplication tables that I so enjoyed as

a schoolkid

In a remarkable section that echoes current advocacy of teaching 'deep' principles, Coleridge reported that his lads were unable to classify and analyse, to separate form and matter, to illustrate, and to explain -- they might have learnt some facts but 'they cannot combine or apply them, or so much as recognise them in an altered dress' (page 21).

An effective way to introduce these deep principles was to teach Latin: to instruct via 'repetition of the Latin grammar' and then permit 'the construction of a few easy Latin sentences'. Teaching science would not do this: it would not 'humanise their coarse and rude natures...gentle their condition'. Hence the College's motto -- abeunt in studia mores (page 22). Science offers no examples of conduct, no standards of beauty. And if students learn Latin they can also better understand the Anglican liturgy. In this way Latin teaching became a 'characteristic of the institution'.

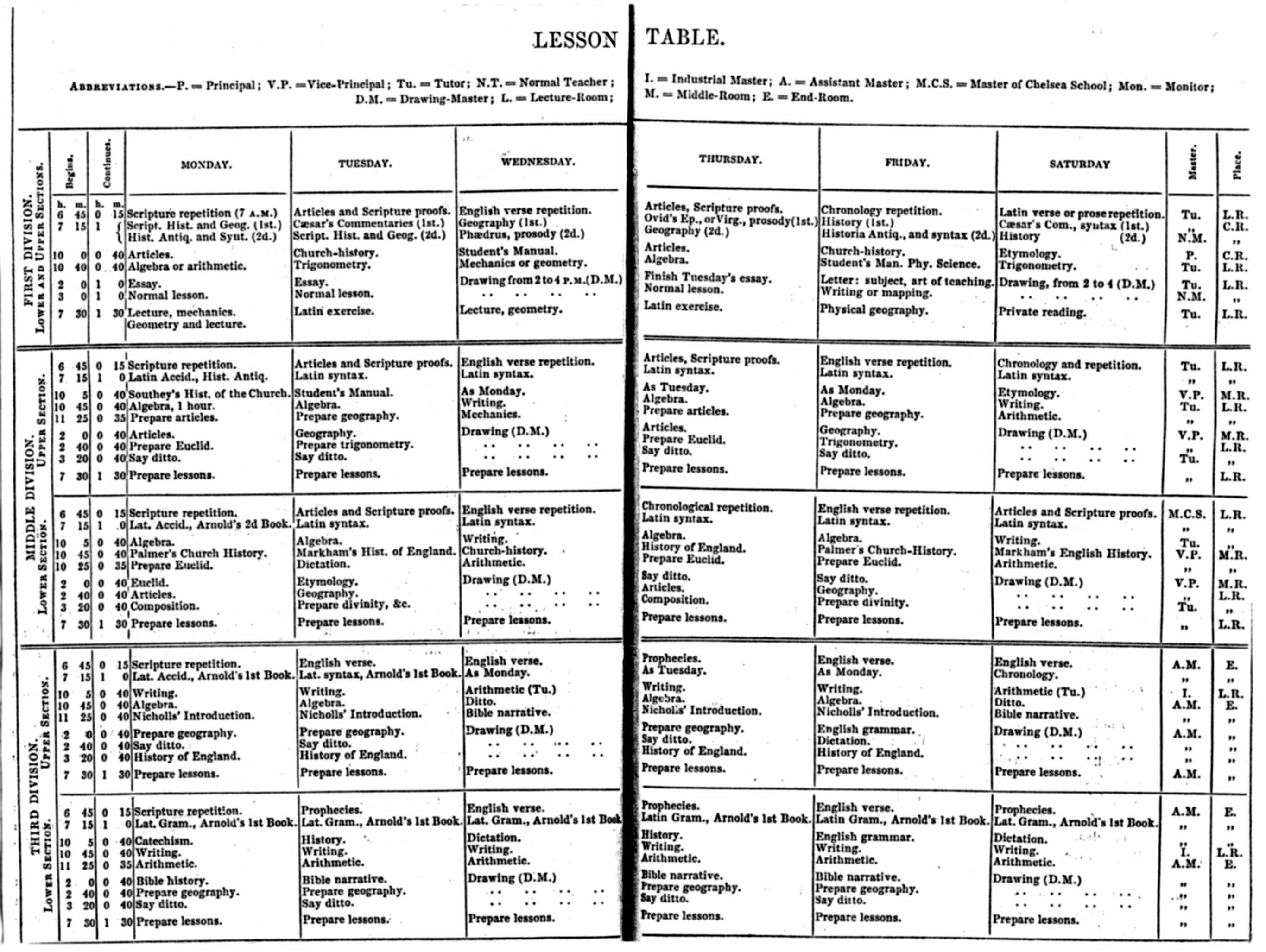

As can just be seen form the lessons above, the students were organised in three divisions, according to their year, with two sets in each, divided by ability. The poorer scholars received as much individual help as was possible. They taught in the practice school every alternative week for 12 months -- see the details of lesson times below.

Tight controls were exercised over the students' reading matter. There was a list of approved books, included in the Letter. Students could also bring their own books to be approved by their masters. Any unsuitable books would be frankly criticised by those masters, and their 'falsehoods' exposed. In this way, 'One way of thinking and feeling is alone recommended, or habitually exhibited, to the students' (page 24).

Coleridge justified the morning service as good for them, even if many were ignorant of Christianity. He agreed that it was only of religious benefit if religion were equally taught at home, but still saw a function -- to 'curb the unruliness and tame the wildness into which the spirits of unregulated childhood are sure to degenerate' [original emphasis] (page 34). Ideally such rituals should lead to self-control. Some pupils did indeed become devout, however, and to encourage this all were supplied with Bibles and prayer books.

A pupil was admitted at age six. Coleridge noted some demand from parents for earlier admission, and considered the need to recruit a schoolmistress to teach younger children.

It was also possible for trainee teachers to practice at the Chelsea School. Here they would encounter children from 'humble' or even 'abject' domestic conditions . They were mostly 'free list' children. This school was happy to accept teachers from St Mark's, since it relieved their funds: the College was happy to let teachers experience this school as a more realistic preparation for their future careers.

Examinations and Testing

Coleridge discusses the role of examinations. He was not against them, but he saw the cultivation of the mind rather than acquiring knowledge itself as the most important thing. The child's mind was a garden, and plants in it had to be cultivated carefully. Mental capability was the issue, and the way to judge this was to hear a child read, 'observe the countenance', attend to the 'intonations of voice' (page 40), and generally to 'discern the ineffaceable mask, if it be there, which education stamps upon the mind'. Persons mattered rather than things, learners rather than what was learnt. It was easy to be deceived by fluent answers, especially if they were learned by rote. In a footnote, Coleridge notes that such deception often involves collusion among teachers too (page 40).

Schools should be judged according to whether they foster 'intelligent reading'. This is the essential skill, which underpinned all the other subjects, including Bible instruction. It was necessary, of course, to combat 'the false views of society laid before him by the Owenist, of constitutional government by the Chartist, of the Church by the Independent and the Romanist' (page 42), which 'circulated in every pot house'. These seditious views were to be countered by reading school History in particular, although Geography was very important too. [And as we have seen, a robust criticism was on offer from any master of such reading material]

Coleridge's views on arithmetic look heretical by modern standards. Arithmetic is useful, but there was no need to exaggerate its importance. Much anxiety about teaching arithmetic was simply misplaced: even petty tradesmen were able to do it successfully, so it was unlikely that there would be any 'eventual deficiency' among the population (page 43). It was certainly not right to select prowess in arithmetic as the main test of the overall efficiency of a school. Much money had been spent on teaching it, but it was best to leave it to take care of itself. Reading, on the other hand, was much less widespread and should be fostered -- after all, the Church itself advocated reading.

Coleridge was not in favour of judging whole schools by examination results, preferring more considered judgments instead ( including the use of Inspectors). He welcomed inspections of his own College -- a recent Inspector had been 'severe and impartial, as coming from without -- appropriate and helpful, as agreeing with that which is within' (page 45). However, excessive inspection [twice a year in his case] would have as a 'pernicious' effect, especially in unsettling students.

Choral Services

There was one other item of controversy. The services in the Chapel featured choral music, which was usually found only in cathedrals. Coleridge argued for choral music in College as he had done in schools -- on the grounds of its social function. He considered a number of other objections, such as that he had secularised the service by making it into a music lesson. He denied this -- it was a first step towards, although not the same as, actual devotion. He also claimed the service was kept deliberately low key, to edify rather than to 'puff up' [over-excite?] the participants. Some critics raised the old doubts of excessive standards -- if students were used to such services at College, how would they fare if they had to work in small villages with simple church services? Coleridge simply hoped they would retain pleasurable memories of College, with no resentment of their present state.

High Standards, Low Quality Students

Coleridge's final thoughts include overcoming the problem of reconciling high standards with average quality entrants by advocating splitting the College by age into a public school, and a university. He ended with a plea for proper and satisfying careers for his graduates, to continue the good work of the College -- teachers would require 'moderate comforts, recognised respectability, social encouragement, opportunity of promotion' (page 68).

Coleridge, D (1861) The Education of the People, a letter to the Rt. Hon. Sir John Coleridge, London: Rivingtons (and the National Society -- Marjon archive)

This is a criticism of the Revised Code, and the monitorial system. [NB Samuel T Coleridge had delivered a famous lecture at the Royal Institution in 1817 on the inadequacies of Lancaster's methods – they offered cruel and unusual punishment which would brutalise the pupils and stifle the growth of the imagination, he argued – and imagination, especially in aesthetics, had strong links to cognition for him – see Holmes' 1999 biography -- Coleridge: the darker years]. Some graduates of monitorial schools had been invited to compete for a scholarship to St Mark's and one could hardly spell, while the others could write out the Creed but not separate the words! Coleridge pointed out that these were schools that had been well financed already!

Coleridge defends the need for high standards of education for school teachers, on the grounds that they will bring moral and social benefits more generally. He is aware that St Mark's had been especially open to criticism for the high standards offered to its graduates: however his goal was to raise all to high standards, rather than level any people down.

His letter ends with a nice analogy about a maker of cider who improved his apples to make better cider -- the apples became so good that people bought them to eat. His landlord protested, and demanded the return of the old crabs!

Coleridge D, (1862) The Teachers of the People, London: Rivingtons and the National Society [and Marjon archive]

This is also addressed to Sir John Coleridge. Derwent Coleridge claims his College had made a great impact on cohorts of students who had come from culturally impoverished backgrounds -- his descriptions of early students are far from flattering! He argues that the teachers of elementary school children must offer the highest levels of 'mental cultivation' and that 'mental cultivation' cannot be dissociated from teacher-training.

The pamphlet also addresses possible criticisms of this policy, evidently ones that actually had been made. Coleridge denies that high standards will lead to discontent among the teaching force [apparently, some teachers had left teaching for the higher professions], or that they will help make teachers independent of the clergy. Coleridge was determined to raise the status of teachers, despite the efforts of the Revised Code to reduce it [ to a somewhat technical level -- as in monitorialism]. He saw teacher-training as about cultivating 'the attributes of a gentle nature... in the deep soil of Christian principle' (page 27). He also saw the need to wage incessant war against the 'vulgarity of the mind', by which he meant matters such the 'coarseness of language and demeanour, boisterous rudeness'. (page 27) He even wanted to shape the speech of trainee teachers. He was aware that student teachers would be motivated to submit to the ( taxing!) regime of St Mark's not only to enter a profession, but to achieve social respectability. He was determined to deal with them 'with equality' [surely not to treat them as equal to himself though -- equal to each other, despite their differences in ability and 'cultivation'?].

CRITIQUE

Unfortunately, we do not

have a ready-made

heavyweight critique to hand. Important as they might have been

locally and nationally,

the founding principals of the College of St Mark and St John did not

attract

the attention of Marx or Foucault (although both can be linked pretty

directly

with Bentham and thus with monitorialism -- see

file). [Actually I now discover this was mistaken: both Marx and

Engels commented directly on the work of 'Dr Kay', as Kay-Shuttleworth

was originally known, and used him as an example of the mistaken

'political reformist' emphasis of liberal figures -- see file].

While I am here, I have

also

found a

web file offering a possible link between Charles Dickens and

Kay-Shuttleworth, who corresponded about education, apparently.

Dickens' worries about Kay-Shuttleworth's approach might have inspired

the character of Mr Gradgrind in Hard

Times, it seems! An alternative is provided by Seed (2005):

...there is no lack of evidence that clergymen and voluntary-school committees, Anglican and others, often did look on their teachers, male and female, as little more than servants. Like Dickens' Mr M'Choakumchild, the certificated teacher might, their superiors believed, possess a superficial knowledge of a range of subjects but this was not enough to disguise a fundamental lack of culture and breeding. Class origin will out, despite two years in a training college.

Here, we might try out a

marxist

approach, as outlined

in the file on Bentham, seeing the ideas of Coleridge or of

Kay-Shuttleworth

as ideological in the two senses we have discussed:

- as contaminated by the personal values and social class values of the persons concerned thus it would be easy to see Coleridge's views about seditious reading as simply reflecting the values of the religious elite.

- as a series of misleading abstractions based on the wrong level of analysis this would proceed by using the concepts of 'the reproduction of the social relations of capitalism' as with Bentham.

A discourse is a set of connected statements. So far so good. However, a discourse also refers to the insitutions in which those statements are expressed or embodied. Further, in Foucault's hands, the formation of discourses is what lies behind the emergence of expert forms of analysis, such as academic disciplines and their 'schools', as well as the more popular versions of them, including those 'applied' to practice. All expert views are open to this analysis -- including marxism. Discourses are not just 'science' in other words, and they are not just ideology either, in the crude sense of representing the class views of the experts. There is another problem, for marxists especially, concerning the way the statements in discourses actually get connected together.

Some marxist theorists, who also use the term discourse, refer to some process of 'articulation'. Here, basically, it is the dominant class or their agents who link together various statements into a coherent discourse (meaning a political or academic programme). A good example of this approach would be, say, Hall's account of Thatcherism ( see Hall S and Jacques M. (eds) (1983) The Politics of Thatcherism, London: Lawrence and Wishart and Marxism Today) ( Better still, see my own wonderful critique in Harris D (1992) From Class Struggle to the Politics of Pleasure, London: Routledge)

For Foucault, this probably overdoes the integrating role of a class agent. Of course there are actual experts or intellectuals, including tame bourgeois ones, who do attempt to link things together -- in the case of Thatcherism, things like English nationalism and a sense of Europeanism, for example, or traditional values and a modernised economy, or a notion of national identity and a sense of vocational relevance in curriculum design. But Foucault also wants to insist that statements have some 'pre-discursive' connection among and between themselves, and, for that matter, that the objects mentioned in discourses also share some connections. Finally there is the notion that a discourse has some positive effects, enabling thought and action to take place, and progress to be made -- this is more than the marxist sense of discourses which repress, contain, and keep things under control by limiting possibilities. (For a further discussion see my aside on Foucault) ( and, for keenies, the reading guides to Foucault here and here)

One of Foucault's favourite examples concerns sex and sexuality ( try his very readable The Use of Pleasure: the history of sexuality, especially vol 2, London: Peregrine Books, 1985). There have been a number of discourses about sex and sexuality, of course, quite often involving an attempt to regulate the sexual habits of undesirable groups (such as the undeserving poor, recent immigrants, those with moral or physical flaws). Sex happens to be a convenient object for such discourses, because it permits specific statements to be made about a wide range of matters -- the relations between adults, the duties and responsibilities of parents towards children, concerns about overpopulation, sexual hygiene, the moral basis and standing of the nation, concerns about social change, and the ways in which people should conduct themselves. The specifc statements cohere into a whole discourse, with its own effect. Of course, regulatory discourses are the most obvious ones, and there are some easy examples -- Marie Stopes in the UK, Nazi Germany's selective breeding programme, sex education in the 1950s ( when I was a pupil -- all deep embarrassment, guilt, obscure diagrams of rabbits, heavy warnings of death, sin and disease, no mention at all of any pleasures), the periodic scandals about sterilisation cases involving the 'mentally handicapped', and so on. Foucault wants to insist that Freudian analysis is also really a regulatory discourse concerning sex, despite its scientific and liberating appearance -- the therapy room, where patients are forcefully asked to confide their most intimate details, is merely a scientific version of the Catholic confessional itself.

However, current sexual behaviour is much less repressed -- but it is not just free from discourse, or just 'natural behaviour' which is 'discourse-independent', so to speak. The discourse has changed, of course, and is now far more 'permissive', but it is still regulatory in setting standards of conduct. It is now also permitted to talk about sex far more openly than in the past, and Foucault insists that that this is not the lifting of some Victorian repression but merely the effect of the new permissive discourse. As you might expect, such commonplace talk (and visuals, TV programmes etc) about sex has a positive side too.

Indeed, there is almost a sense that heterosexuality is now in rather a precarious state and needs to be 'talked up'. A former student of mine took this view on analysing a series of television programmes about the risk of AIDS -- the frequent urging of the audience to engage in 'safe sex' by the experts was also a strong encouragement still to engage in heterosexual activity, she argued. Indeed, a young girl who claimed to be celibate shocked the panel as much as any coyly reported 'deviant' sexual activity, and she was openly laughed at, and treated with the most intolerance.

Now let us turn from sex to education, and see if we can apply Foucault's notion of discourse to the statements we have read above. It is interesting first of all to isolate and collect the set of statements in the work of Kay-Shuttleworth and Coleridge. It is clear that they are not just talking about education as a technical matter, but are also talking about standards of conduct and behaviour, and the politics of education, in terms of their funding and regulating bodies. Perhaps it is the case that education too is one of those convenient objects about which statements may be collected into a coherent discourse?

No doubt this is because education concerns young people, and we feel the need to offer young people moral guidance and standards of conduct as well as technical knowledge for its own sake. We can see from both monitorial and pupil-teacher systems that the organisations in which they operated were thus both strongly disciplinarian, even 'puritanical'. We can read of Coleridge's defence of the teaching of Latin on moral grounds, and learn from the college motto that the 'civilising' function of education was as important as the skills it was supposed to provide trainees. We can also detect quite easily a concern for saving the State money, or the National Society, and of the need to keep regulators well-informed and onside. There is also a need to maintain commercial viability -- even where this is admitted to be unhelpful for the educational life of the College.

Finally, the different 'parties' then active in politics also are to be considered -- especially the 'church party' and its secular and non-conformist rivals. Perhaps the debates about the monitorial method illustrate this even better: if the sources are correct, any differences between Bell and Lancaster in purely technical terms were exaggerated and amplified in order to permit a place, as it were, for the different parties to take sides. The educational discourse in the early 19th centuries permitted religious parties a public arena, to demonstrate their views, and to distance themselves from their rivals. At the same time, those parties tried to control the discourse still further -- but eventually lost a dominant part as the State gradually provided more input. In other words we have a complex relation between the discourse and those parties who appear in it and try to control it

We shall find the same concerns mentioned together again and again in subsequent legislation as well. These themes seem interwoven and inseparable. New 'parties' arise, of course -- they might include parents from the 1980s onwards -- but they still have to situate themselves in this long-established discourse. Parents, of course, are oftern as keen as any party to see 'proper education' as a matter of moral guiance and discipline as well as 'acquiring knowledge'. Practising educators also need to be able to pursue arguments according to each of these themes -- never just to consider the technicalities of teaching and learning in isolation, but to be aware of the requirements of all the parties and all the issues. Perhaps it follows that educational researchers should not attempt to separate out these themes either?

Above all, the media still weave together the same elements in the same discourse in the frequent 'moral panics' about education, 'standards', the discipline of the young, the dreadful behaviour in 'inner city' schools, the occasional deviant teacher, the expense of State education, the issues of parental choice, the safety of the young, the future employment of the young, social change, adverse comparisons with the education systems of our competitors -- and so on.

Finally -- try it for

yourselves.

What exactly are the elements, and how are they combined, in New

Labour's

slogan 'Education, Education, Education!'